In the early 2000s, Bastakoti rented office space near Taj India, an Indian restaurant in Salt Lake City. Bastakoti ate there often and one day the owner approached him with a proposal: take over the business. Bastakoti jumped at the opportunity and in 2004 took over the restaurant and renamed it Himalayan Kitchen.

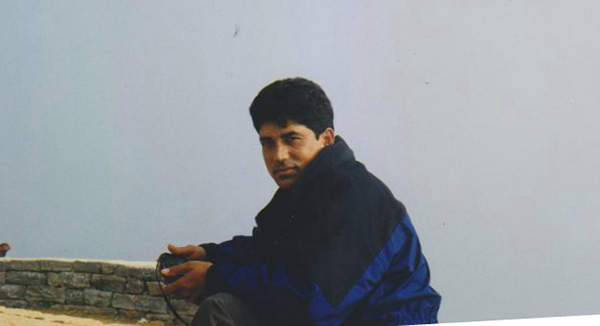

In the early 2000s, Bastakoti was living and working in Salt Lake City. His plan had been to open a travel company that would facilitate trips to Nepal and the surrounding region. But a state department warning about unrest in that part of Asia was hurting his business and travelers were scarce.

At the time, Bastakoti rented a shared office space near Taj India, an Indian restaurant. Bastakoti ate at the restaurant often and one day the owner approached him with a proposal: take over the business.

Bastakoti jumped at the opportunity and in 2004 took over the restaurant and renamed it Himalayan Kitchen.

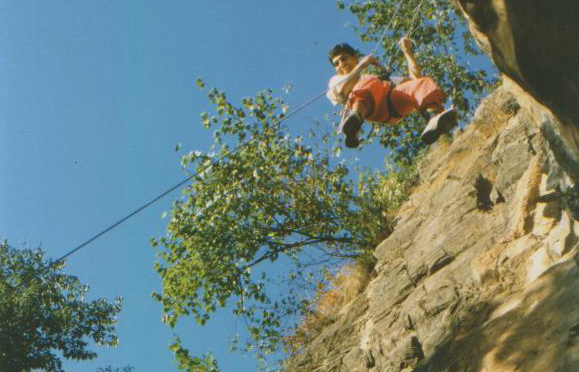

Bastakoti first arrived in Utah in 2001 for paragliding training. Though he had been running a paragliding tourism business in Asia, he didn't yet know how to pilot himself. Today, Bastakoti still occasionally spends time soaring over the Wasatch Front.

Bastakoti was born in 1967 in Gorkha, a region of Nepal that he said is famed for its "brave fighters." His father worked for the local telecom company and Bastakoti would hand crank the old telephone so his father could receive messages. Gorkha is a mountainous region and Bastakoti said he used to gaze with curiosity at a nearby peak.

"I could see the mountain," he recalled. "I always asked my dad, 'what is behind the mountain.'"

It also was during this time that Bastakoti had his first real experiences with cooking. He said his mother was the chef in his family and when he was only 9- or 10-years-old she helped him understand how to balance spices, mix curries and improvise for the best results.

By the mid 1980s, Bastakoti, now in his late teens, had graduated from high school and planned to attend college in Katmandu. But — much like teenagers in the U.S. — he had a gap of a few months between the end of his high school classes and his move to the bigger city. So Bastakoti traveled, going for the first time beyond the mountain he had watched for years. He said his father gave him some money and he set off — on foot. For about the next month, Bastakoti walked the mountain trails of Nepal. When he was tired, he knocked at strangers' doors for shelter. When he was hungry, those he met on the road fed him. "The guest is equal to God," Bastakoti explained.

After traveling for a summer, Bastakoti moved to Katmandu for college. He studied tourism and economics. Bastakoti's father him money, but life in the city was more expensive and he took a job at a hotel to help make ends meet. One day while working, a British couple asked him about the Ganesh Himal, a holy mountain range he had recently visited. The couple was looking for a guide and Bastakoti said he could take them. It was half a joke, but the couple took him up on the offer.

A year after Bastakoti led his first tour, the British couple's friends showed up wanting the same experience. Soon, Bastakoti was making more money as a guide than he was at his hotel job. So he quit and spent the next 16 years leading tours through Nepal, Tibet and India. Eventually, that tourism business evolved into a paragliding business — which is how Bastakoti first learned of Utah. Nepal is a good place for paragliding, he said, because aficionados can take to the skies all year. Bastakoti said one of his clients came from Utah and mentioned that it, too, was a major paragliding destination.

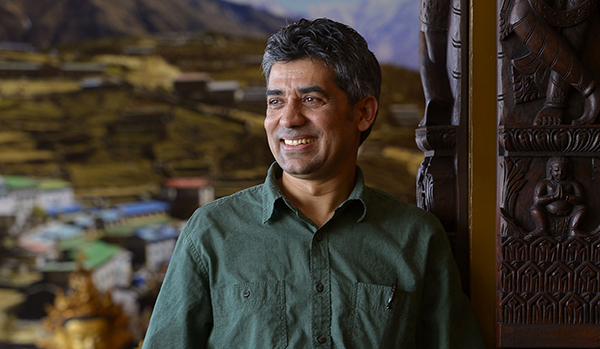

On an unseasonably warm winter day, Surya Bastakoti works the checkout counter at Himalayan kitchen. As a young couple pays for their meal and moves toward the door of the restaurant, Surya smiles broadly and walks with them, chatting warmly about his homeland thousands of miles away. Bastakoti spends much of his time at his own restaurant, often eating two meals a day there. Sometimes he just walks through the dining area, surveying his guests.

And then sometimes, he's gone.

Bastakoti still has strong ties to his native land, traveling there often to lead tour groups and visit family. Sometimes, he even brings back rare spices that he can't find in the U.S. Many of those spices don't have English names, he said, but getting the fresh is important for producing food that actually tastes as he remembers it.

"We take seriously the cooking," Bastakoti said.