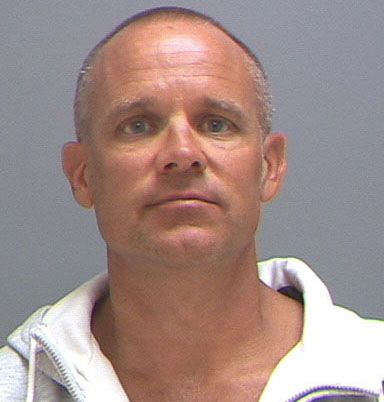

Utah Attorney General John Swallow has come under scrutiny on a number of fronts:

John & Jeremy

In September 2010, John Swallow, then Utah's chief deputy attorney general, corresponded with St. George businessman Jeremy Johnson about a federal investigation of Johnson's I Works business.

Johnson alleges Swallow helped with a strategy to stifle the probe. Johnson and a partner ended up paying $250,000 to Richard Rawle, the late founder of the Provo-based Check City payday-loan chain, who in turn paid a Washington lobbyist and a Las Vegas lawyer with close ties to Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev. Johnson has said the money was meant as a bribe to persuade Reid to help shut down the I Works investigation. Johnson and Swallow discussed the deal during their now-infamous meeting at an Orem Krispy Kreme doughnut shop — an encounter that Johnson secretly recorded. Johnson, who now faces 86 federal charges from his business dealings, later tried to shield Swallow from prosecution in a plea deal that went awry. At the same time, Johnson asked federal attorneys how it might help him if he offered evidence in "the Swallow thing."

Swallow's response: Swallow insists the arrangement was strictly for lobbying. Reid has denied any knowledge of the deal. Rawle, in a deathbed declaration drafted principally by Swallow's attorney, also maintains the money was for lobbying. Read the story

Cement Consulting

Swallow pocketed $23,500 of the money Johnson paid to Rawle, but argues it was for consulting work on a Nevada cement project.

Swallow did not report the payment or his stake in the consulting company on his candidate financial disclosures.

Swallow's response: Swallow says he didn't have to disclose the payment because the company is held in trust for his children. The lieutenant governor's office determined this failure to report the payment violated Utah election laws. Read the story

The Houseboat

During their meeting at an Orem Krispy Kreme doughnut shop, Swallow asked Johnson if there were any records of Swallow using the St. George businessman's luxurious 75-foot houseboat.

"Is there any paper trail on that?" Swallow asked Johnson. "There's no paper trail on the houseboat," Johnson answered. "Nobody knows about it." Swallow used the houseboat at Lake Powell in 2010, while he was chief deputy attorney general.

Swallow's response: Swallow says he believed use of the boat was a gift from a friend and that he paid for the fuel, food and personal watercraft. Read the story

Making Deals

In February 2010, Swallow contacted Johnson on Rawle's behalf, trying to arrange business deals between Johnson and Rawle's cash-for-gold business and with Check City. The deals ultimately fizzled.

The deals ultimately fizzled.

Swallow's response: Swallow's attorney says his client was wrapping up business that he had started months earlier, before he had joined the attorney general's office. Read the story

Protection for Donors

Three Utah businessmen in direct marketing and Internet sales told The Salt Lake Tribune that, in 2009, while raising money for a potential U.S. Senate bid by then-Attorney General Mark Shurtleff,

Swallow indicated that it would be beneficial for them to give money to Shurtleff in case their businesses came under regulatory scrutiny

Shurtleff's & Swallow's response: Shurtleff denies he ever gave donors special treatment. Swallow also says the accounts are false and adds they are "hiding" behind anonymity. The sources requested anonymity fearing reprisals by the attorney general's office. Read the story

Talking with Targets

During his campaign for attorney general in 2012, Swallow was recorded during a phone conversation with a call-center operator who was being fined $400,000 by the Utah Division of Consumer Protection.

Swallow told the business owner, Aaron Christner, that the division was dysfunctional and that, if he were elected, he would try to move it under the attorney general's office. He offered to help Christner get in contact with Shurtleff to discuss his case. The A.G.'s office was counsel to the consumer division.

Swallow's response: Swallow says he did nothing unethical. Read the story

Marc Jenson and the AG's Office

In early 2008, Marc Sessions Jenson was trying to hammer out a plea deal on securities-fraud charges.

Jenson says then-Attorney General Shurtleff told him to make regular payments to Shurtleff's friend Tim Lawson. In a plea deal, Jenson was required to pay $4.1 million in restitution. In 2009, receipts show Shurtleff and Swallow visited Jenson's posh villa in Newport Beach, Calif., charging golf and meals on Jenson's dime. Swallow returned in July with his wife. Jenson says he paid Lawson in excess of $200,000. Jenson says he had no choice but to pay their tab and alleges he was extorted.

Shurtleff's & Swallow's response: Swallow says he was an attorney in private practice, and there was nothing improper about the trips. Shurtleff says Jenson is a liar out for revenge. Read the story

Jenson and Mount Holly

Jenson contends that Swallow offered to help with the now-abandoned development of the $3.5 billion Mount Holly ski and golf resort in Beaver County.

Jenson said Swallow promised he could use his influence in the A.G.'s office to help with the project. In exchange, Jenson said Swallow demanded a cabin and ownership stake — valued at $1.5 million — in the resort. Jenson was unable to develop the resort and faces new charges stemming from his recruitment of investors. Jenson accuses Shurtleff and Swallow of shaking him down for hundreds of thousands of dollars. The A.G.'s office also has stepped aside from the Mount Holly case and handed over prosecution to the Utah County attorney's office.

Swallow's response: Swallow says he was in private practice at the time and did nothing wrong. Read the story

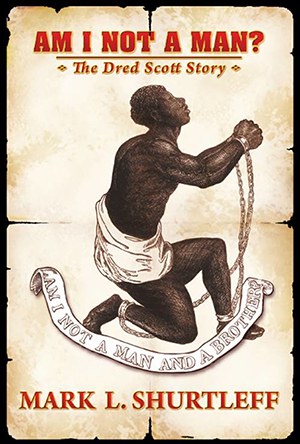

Buy the Book

In 2008, Pre-Paid Legal Services, which had donated more than $130,000 to Shurtleff’s campaign, agreed to buy 100,000 copies of a book he had been writing, Am I Not A Man? The Dred Scott Story.

The deal would have netted Shurtleff a six-figure payday, according to the owner of the publishing company, Candace Salima. But it fell apart. Instead, 10,000 copies were printed. Pre-Paid bought 6,000 of them and another 2,500 were sold at stores. Shurtleff bought the remaining 1,500, Salima said. In addition, Jenson says that Shurtleff asked him to buy $250,000 worth of the book and told Jenson that he wouldn’t need to receive the copies. Shurtleff would get royalties for the sale.

Shurtleff's response: Shurtleff says he never made a dime on the book deal and that Jenson is lying about the offer. Read the story

Millions At Mimi's

In 2009, Shurtleff offered to get $2 million from Jenson and pay it to another businessman, Darl McBride, to persuade McBride to take down a website critical of Jenson’s former partner, Mark Robbins.

McBride felt Robbins owed him money, but he couldn’t locate Robbins, who at the time had a warrant for his arrest. In a May meeting at Mimi’s Cafe, Shurtleff said Jenson, who was free on a plea deal with Shurtleff’s office, had “every motivation” to pay the money. McBride secretly recorded the meeting and gave the audio to the FBI. A short time later, Jenson said, Shurtleff and Swallow took a trip to Pelican Hill, where Shurtleff asked Jenson to pay McBride $2 million. Jenson said he was dumbfounded and protested he didn’t have the money. McBride never heard back from Shurtleff.

Shurtleff's response: Shurtleff has declined to comment on the meeting. Read the story

Worldwide Environmental

In December 2010, the attorney general's office was contacted by Nancy Sechrest, a lobbyist for Worldwide Environmental Services, concerned her client had lost out on an emissions contract with Salt Lake County, alleging collusion.

Sechrest, whom Shurtleff had listed as a “major contributor” to his campaign, asked the office to investigate. Shurtleff was undergoing cancer treatments, but Swallow asked an attorney in the office, Alan Bachman, to follow up. Attorneys from the county said they were threatened with a criminal investigation and Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill called the FBI to investigate the matter. In April 2011, Swallow, Sechrest and Bachman were subpoenaed to testify before a grand jury, but the panel was never convened. Read the story