When ex-Utahns lost children at Sandy Hook and in an airport mugging, they faced the question: Do they really believe in resurrection?

By Peggy Fletcher Stack

The Salt Lake Tribune

Resurrection may be easier to believe before your first-grader is gunned down at her school or your adult son is stabbed to death in a faraway airport.

What you once embraced as an abstract theological notion, you now desperately yearn to be real.

Just ask Alissa Parker, an Ogden native whose 6-year-old daughter, Emilie, was slain along with 19 of her classmates and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn.

Just ask another former Utahn, the Rev. Yvonne Lee, a Methodist pastor whose son Sam was awash in blood after a murderous mugging in Indonesia.

Or even the biblical Mary, who hunkered down at the foot of a wooden cross, so the story goes, while her son hung in agony — and then cradled Jesus’ lifeless body when it was lowered down to her.

What happened next is the miracle of miracles that Christians worldwide celebrate every Easter. Several women arrived to wash the body for burial, only to find the garden tomb empty.

A living Jesus, the sacred text proclaims, had emerged. And that is what believers hope for all humanity when they sing their hallelujahs and, with joyful hearts, add the refrain — Christ is risen.

But what if it was an illusion? A perverse hoax? A fabrication?

Alissa Parker, left, and her husband, Robbie Parker, on Dec. 14, 2012, after receiving word that their 6-year-old daughter, Emilie, was one of the 20 children killed in the Sandy Hook School shooting in Newtown, Conn.

AP Photo/Jessica Hill

The night after the December 2012 massacre, Parker, plaintively asked her husband, Robbie, “It’s all true, right? All the things we believe about death and God … it’s all true?”

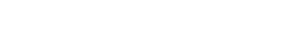

The horror of Emilie being “cruelly stolen” from her, the Mormon mother writes in her new book, “An Unseen Angel,” made her question everything.

The horror of Emilie being “cruelly stolen” from her, the Mormon mother writes in her new book, “An Unseen Angel,” made her question everything.

“My ship of faith was rocking,” she writes, “and the dark sea of doubt began to rise.”

Pastor Lee, formerly of Salt Lake City but now ministering to the First United Methodist Church of Aurora, Colo., found little comfort in glib statements about heaven or the hereafter.

She tried to bargain with the Almighty: She would give up her own life for a chance to touch and speak with Sam — even for a fraction of a second — one more time.

“Why couldn’t God,” she wondered, “resurrect my son right now?”

Seeing, believing

Alissa Parker chose not to look at Emile’s bullet-riddled body at the mortuary, opting to remember the happy child — pretty in pink and even prettier in personality — skipping off to the bus.

But she became obsessed with details of her daughter’s death, so three months later, when police returned the clothes Emilie was wearing on that awful day, Parker gingerly examined each neatly washed item.

There was the purple fleece scarf she had wrapped around her daughter’s neck as a “fashionable accent to her outfits.”

It had six holes likely made by a single bullet passing through the “folds of fleece,” she writes, and which likely killed the girl.

Then the Latter-day Saint mom’s need to know shifted to the ineffable.

“I need to know with certainty she’s OK,” Parker, who now lives in Washington state with her husband and two other children, says she told God. “I need to understand what her life looks like now in order to grieve the old life.”

That quest, however, took a little longer.

Robbie Parker at a memorial for his daughter Emilie in 2012.

Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune

First, Parker had to let go of anger toward Adam Lanza, the shooter.

“He was a monster to me,” she recalls in an interview. “I was angry and comfortable being in that state.”

It took much emotional energy, a spiritual prompting, a screaming rant aimed at the killer (who had taken his own life) and a visit to Lanza’a heartbroken dad to slowly soften Parker’s feelings.

Lanterns are released for the Sandy Hook victims, 2012.

Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune

“I wanted to remain angry because I thought I owed it to Emilie,” she says. “If I let that go, I was letting him off the hook.”

Ultimately, it proved impossible for Parker “to heal and be whole without forgiving him,” she says. “Emilie wouldn’t want me to feel that pain. She would want me to be the best mom for my family and the best person I could be.”

Forgiveness is hardly a one-time occurrence, she says. “It’s a choice I have to make again and again.”

Meanwhile, Parker was looking for signs of her daughter’s continued existence and frustrated that others seemed to see them before she did — even husband Robbie had seen their child in a lifelike dream-vision.

Finally, that first Easter morning after the shooting, the eager mom watched Emilie’s younger siblings, Madeline and Samantha, “swaying and twirling” as music filled their home.

“An enveloping warmth of peace and comfort spread through my whole body,” Parker writes. “And then I felt her. I felt Emilie. Nothing could be clearer or stronger. … I breathed in the blessed sense of her.”

At church that day, she tells The Salt Lake Tribune, “all I could think about was Mary.”

Parker empathized with the mother of Jesus in a way she never had before.

“Not only did her son die in excruciating pain,” she says, “but she watched it and was powerless to stop it.”

Then, the Bible attests, came the resurrection.

Making the impossible possible

Though belief in Jesus’ return to life ranks as a central tenet of Christianity, 19 percent of Americans don’t buy that doctrine, according to a 2013 Rasmussen Reports poll. At least a quarter of British Christians don’t either, says a 2017 survey commissioned by the BBC.

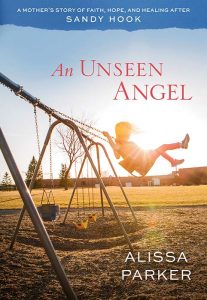

The Rev. Michael Imperiale

Al Hartmann | The Salt Lake Tribune

The Rev. Michael Imperiale, pastor of Salt Lake City’s First Presbyterian Church, insists such skeptics are wrong and that science is on his side.

“Quantum theory has proven that the universe is open,” he says. “Resurrection, as a promise for human beings, seems to be more possible, even probable, with that scientific theory.”

The idea of a physical rebirth “opens up a whole world of hope,” Imperiale says. “It is real, does not disappoint, is more assured, and is not just wishing.”

Even such exquisite hope, though, doesn’t wipe away sorrow, grief and pain at the loss of a loved one, he says. That’s why the crucifixion — ritually commemorated among the faithful on Good Friday — is part of the Christian Holy Week.

Angel, memorial for Emilie Parker

Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune

Too many Americans want to keep death at bay and let the hospitals, mortuaries and cemeteries deal with it, he says. They certainly don’t want to talk about it.

But you don’t reach the rapturous joy of Easter morning without going through Golgotha.

When believers lose loved ones — especially via violent death — they often feel despair and doubt, the Presbyterian pastor says.

The most therapeutic thing they can do is take their feelings — anger, frustration, confusion, disbelief — to God.

“We have to acknowledge the hurting,” Imperiale says. “God can handle our struggles.”

That’s exactly what Yvonne Lee did.

A mother’s arms

On a routine trip to Indonesia for business in fall 2011, 28-year-old Sam Lee was mugged by two men on motorcycles. The thieves stabbed his thighs, robbed him and rode away.

Samuel Lee, son of Pastors Eun-sang Lee and Yvonne Lee

Courtesy of the Lee Family

The Korean-American bled to death under the dark sky, among strangers, far from home — and far from his mother’s comforting arms.

“Not being able to touch him and hold his hands, tell him goodbye or pray for him,” Lee says. “The way he died, it’s really hard.”

Still, she believes, he was not alone.

“God walked with him, whether it was an hour or half an hour, from the time he was stabbed until his heart stopped,” she says. “During that physical suffering, I believe that God was holding him as I would do, that God has feminine characteristics as well as male.”

Yet, the earthly mother longed for one more intimate exchange.

“I prayed and prayed,” Lee recalls. “He came in dreams but never came into reality.”

That is, until one day, more than a year after his death.

“He came as a resurrected person,” she says, and told her, “Mom, you wanted to touch me and talk to me. I am sent for your assurance.”

Sammy (as she called him) then explained, “Don’t think I’m a tragic victim. I am beyond your imagination. Think of me as a blessed angel.”

From then on, the Methodist minister was at peace.

She’s not sure whether it was a dream — the Bible is full of them — but it was powerful and clear.

And theologically confirming.

Jesus is “still breathing and alive in our presence,” Lee says, but may come “in various forms — sometimes as a human being, sometimes as a song or mountain.”

Parker sees little Emilie as an angel as well, dropping into our world to help, heal and lift others.

Like Sammy Lee told his mom, Emilie’s life should not be defined as a tragedy, Parker says, but by “the goodness and light within her.”

That light continues to swell and, for the mother left behind, faith in resurrection lives anew.

Samuel Lee

Courtesy Lee Family

pstack@sltrib.com

Twitter: @religiongal