By Mariah Noble

The Salt Lake Tribune

Hungry, heartbroken and weary, Philip Deng Aguto retreated into the bush and slumped to his knees in despair.

Why, the 18-year-old pleaded with the heavens, had he been allowed to live through so much — slaughters in his native land, barefooted treks across hundreds of miles of sun-scorched desert, raids by refugee-loathing marauders, even a perilous crossing of a crocodile-filled river — only to perish of simple starvation?

“While praying, a picture came to my mind,” he later told a friend, “and I was in a foreign country, and I was helping people … and somehow I knew that it was America.”

His vision became a reality. But this American dream would have a nightmarish end. For Aguto — who fled South Sudan at age 7 and traversed more than 500 miles from one east African nation to another, dodging death along the way — would perish on a dark road some 9,000 miles away in Utah. Alone. Homeless. Destitute. Again.

A month ago, at age 36, he was struck by at least two cars in Salt Lake City. The drivers continued on, leaving him to die in the street.

Aguto had held a job and become a U.S. citizen. But apparent mental health problems — possibly rooted in his fear-filled youth — had prevented him from fully adapting to his new home.

With the help of his close Utah friend, Scott Jenkins, and his younger cousin, Makuei Lueth, it is possible to retrace Aguto’s winding, wrenching odyssey from “Lost Boy” to newfound life and a lonely death.

Refugees on the run

Civil war haunted Aguto’s early years in South Sudan. The north sent armed militias to villages in the south, killing the men and taking the women and children captive.

In many places, boys from ages 5 into their early 20s decided that if these guerrillas came to their homes, they would run. So, in 1987, Aguto fled his hometown of Bor, a city along the east bank of the White Nile, where residents raised cattle and lived in grass-roofed huts, in search of safety. He left behind his mother, a brother and two sisters. His father died in the conflict.

Aguto was 7.

Naked Dinka boys burn dried cow dung to keep mosquitoes off the nearby cows in a cattle camp near Thiet, Sudan July 12, 1996.

(AP Photo/Jean-Marc Bouju)

About 25,000 of these Lost Boys started such journeys. Thousands died en route as they struggled to live off the land in terrains filled with lions and other predators. In the rainy season, the ground became “sticky mud,” Jenkins said. In the summer, it dried out and cracked, scalding their feet.

Aguto and about 20,000 others made it to Ethiopia, where he reunited with Lueth at a refugee camp near Gambela, more than 200 miles from Bor.

There, Aguto converted to Christianity and was baptized into the Episcopal Church. The two stayed at the camp until the government changed hands in 1991.

Aguto was about 11 when the new Ethiopian regime chased out the refugees at gunpoint. Many were shot.

To escape, the refugees needed to cross the rapid and risky Gilo River. Some used a rope spanning the wide waterway. Others rafted across on logs. Some simply swam, taking their chances against the lurking crocs.

“[Aguto] made it somehow,”Jenkins said.

The boys then journeyed by the thousands for several days across the desert — with no shoes, their feet burning again — back to South Sudan, where U.N. planes dropped food to them. A boy darted out to the food-drop area, only to have one of the lifesaving loads land on him and kill him.

Driven from that location, the boys came to yet another desert. After three days, they saw a pond in the distance. Some dashed toward the water. But the pond’s owners shot at them, so the boys kept walking.

Eventually, they reached Kenya and a refugee camp called Kakuma.

This camp had schools, and some boys began learning English with hopes of migrating. But the dangers didn’t disappear. A hostile neighboring tribe used the young refugees as target practice.

For 10 years, these wanderers lived on starvation rations: a bowl of cornmeal once a day.

Finally, in 2001, at age 21, 14 years after fleeing his homeland, Aguto arrived in the U.S.

Pizza, ice cream and America 101

In Salt Lake City, he, Lueth and four other Lost Boys shared an apartment.

Philip Deng Aguto, shown in his green card photo. (Courtesy/Scott Jenkins)

Jenkins met the group doing inner-city outreach for the LDS Church and invited the tall, thin Lost Boys to his South Jordan home for dinner.

The family served pizza but none of them liked it. “It was so alien,” Jenkins said. “They’d been living on cornmeal for years.”

Aguto was the only one brave enough to try ice cream, but he quickly got a brain freeze.

The newcomers were surprised when they saw women driving and no guards standing outside banks.

“It was culture shock for them and learning for us,” Jenkins said. “They were just a delightful group of kids.”

As the men were learning English, Jenkins used the expression “it’s like eating an elephant — one bite at a time.” One of the Lost Boys responded that his band of refugees had, in fact, once eaten an elephant. It took them three days to consume it.

Run-in with polite police

Jenkins felt a special bond with Aguto.

“It was one of those unusual things,” Jenkins said, “where you’re natural friends with somebody from a completely different outlook and culture.”

Scott Jenkins

Scott Sommerdorf/The Salt Lake Tribune

Soon after moving to Utah, Aguto joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“He was the first of the Lost Boys to be baptized,” said Claron Twitchell, who became friends with Aguto through volunteering with the International Rescue Committee. “He was very proud of that.”

Jenkins said Aguto was “one of the most courageous of the Lost Boys.” He didn’t shy away from trying new things — riding the bus or going to church alone.

Aguto got a job with LDS Church Printing Division, where Amram Musungu met him in 2003. The two became roommates.

He was always smiling and cracking jokes, Musungu said. “He would call in the middle of the night … and he’d say, ‘Oh, yeah, Amram, I just wanted to say, Hi.’ I was like, ‘OK, thank you.’ You know, his sense of humor — he’s such a good person.”

After some time, Jenkins said, Aguto bought a car, but his lack of schooling held him back from getting a license.

Jenkins said Aguto was pulled over and warned at least once by police officers who were “very gracious.” Aguto continued to drive, however, and when he was stopped again, a more aggressive cop threw him in jail.

Jenkins bailed him out. Aguto told him that “in Kenya if we did something wrong, the police would beat us with sticks until we felt nearly dead.” The police here were “so polite” that Aguto didn’t take them seriously.

Aguto eventually learned English, Jenkins said, and became a U.S. citizen June 12, 2013.

‘Ignoring a major problem’

“He projected to be just a happy, pleasant, glad-to-see-me type of person,” Twitchell said. “But I also know he swung the other way. … A lot of these people who come here on refugee status, they went through so much. They saw people being killed and dying and being shot.”

Musungu said Aguto had mental health problems that held him back. Originally from Kenya, Musungu argues refugees are given inadequate resources to address such issues.

“We’re ignoring a major problem here,” he said. “I would wish [the people who help refugees immigrate] went extra miles in trying to monitor the status, especially the mental status, of these refugees.”

Officials have made strides to provide better care, said State Refugee Coordinator Gerald Brown. For example, when Aguto came to Utah 15 years ago, the state would have supplied help for about three months.

Now, Brown said, refugees are assigned a caseworker — usually someone from the same ethnic background — who follows up with them for two years. Refugees also are connected with mental health services if they need them.

From hope to homelessness

After moving out of the unit he and Musungu shared, Aguto bounced between housing arrangements, including stays at the homeless shelter.

At some point, he felt he had been wronged at work and quit his job despite Jenkins’ efforts to persuade him otherwise.

“He never got stable again after that in terms of his finances,” Jenkins said. “He had a hard time for the last seven [or] eight years.”

According to court records, Aguto was charged with public intoxication more than once. Musungu recalled a time when he was driving near where Aguto later was killed and saw him on the street, talking to himself.

“I was just so sad,” Musungu said, “because he left a very good environment where he could live and enjoy [and] better his life.”

The scene when Philip Aguto was killed in a hit and run. (Courtesy/KUTV)

Aguto’s body was discovered Aug. 13 by Salt Lake City police about 5:30 a.m. near 1400 West and North Temple.

Based on evidence, he had been struck at least twice by eastbound hit-and-run drivers, said Detective Greg Wilking, adding that police are still investigating.

Motorists would have been using headlights, Wilking explained, but Aguto still would have been “hard to see” in the dimly lit area, away from any crosswalk or intersection. His body was found shrouded in a dark blanket.

Security footage from a nearby building showed Aguto riding his bike on the south side of North Temple some time before he was hit, Wilking said. Police found it in nearby bushes.

The trauma to Aguto’s body was “so extensive,” Wilking said, that it would be impossible to tell whether the 6-foot-tall man was standing, sitting or lying down when he was initially hit.

‘We could have done better’

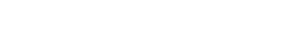

A portrait of Philip Deng Aguto was displayed at his funeral service in All Saints Episcopal Church in Salt Lake City on Friday, Aug. 26, 2016. (Courtesy/KUTV)

Musungu said he has “never been hurt so much and felt so heartbroken” as when he heard of Aguto’s death.

“We have lost such a good person who is just so kind. … I have never seen him fight with anybody. … He was very concerned about how he wanted others to do well.”

Aguto’s funeral and memorial service took place at All Saints Episcopal Church in Salt Lake City. His picture on the program was taken from a police mug shot.

Speakers shared memories of him, and many from the Sudanese community attended, singing hymns in their native Dinka tongue.

“We as a community have to think of a way to engage these young people and get them the services they need and connect them to the community,” Brown said. “ … I’ve got this kid’s picture up on my bulletin board so I don’t forget it, because I think we could have done better.”

Twitter: @mnoblenews