From NASA to Indigenous rights, high school debaters spent the year tackling how to preserve water resources for future generations.

By Saige Miller | Photography, videography and gifs by Trent Nelson and Rachel Rydalch

This story is part of The Salt Lake Tribune’s ongoing commitment to identify solutions to Utah’s biggest challenges through the work of the Innovation Lab.

[Subscribe to our newsletter here]

It’s easy to mistake high school policy debaters as auctioneers in training.

The two-partner teams talk so fast, it’s often incomprehensible to an untrained ear. Debaters do speed drills to practice speaking, or “spreading,” as quickly and articulately as possible. The purpose is to jam as many arguments into a speech before the timer goes off.

But behind the rapid spitfire lies a wealth of knowledge pertaining to the real world.

“The speed of it forces you to really think on your feet really quickly,” Sterling Peterson, a state policy debate co-champion and senior at West High School said, “and being able to synthesize all that information and understand it in a short period of time is really fun.”

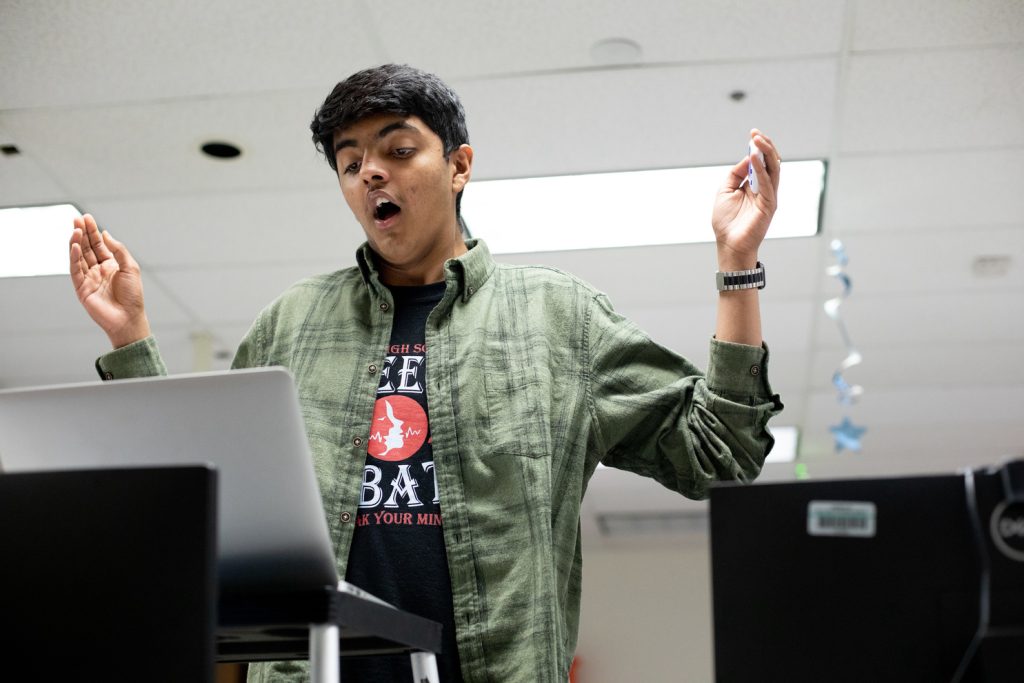

Rachel Rydalch | The Salt Lake Tribune) Policy debate team member R. Sterling Peterson, practices his event with his teammates on Friday, March 18, 2022. He holds a timer in his left hand to keep track of where he is at.

This past year, Peterson, along with every other high school policy debater across the nation, channeled their energy into one topic with unique importance to Utah in light of our ongoing mega drought.

Resolved: The United States federal government should substantially increase its protection of water resources in the United States.

Mike Shackelford, the head coach of Rowland Hall, one of the most successful speech and debate programs in Utah, will be the first to say debate isn’t easy. He’s been involved in the activity for a total of 26 years, both as a competitor and a coach.

“The debate season is long and it requires a lot of work and it requires sacrifice,” he said, “whether it’s sacrificing other extracurricular activities or family time. You have to dig deep in your pursuit of personal growth and personal excellence.”

Unlike most high school athletic programs, the debate season is year-round. Tournaments take up entire weekends and often run behind schedule. Debate research can be dense and complex. Kids frequently lose debate rounds they spent hundreds of hours preparing for.

We’re discovering answers to tough questions that most adults aren’t even thinking about

Out of the 25 nationally recognized events in high school speech and debate, policy is known for being the most demanding—and not just because they talk a mile a minute.

Shackelford, who was a policy debater in high school and college, considers the event to be “the most challenging intellectual activity available to high school students,” due to the extensive amount of research, critical thinking skills, quick comebacks and arguments needed on both the affirmative and negative to be competitive in the game.

Students who compete in policy are committing themselves to a year’s worth of research on a single topic. They’re forced to dig deep into a complex issue, cultivate innovative arguments for and against the selected topic, and pose solutions of all kinds.

“We’re discovering answers to tough questions that most adults aren’t even thinking about,” Shackelford said.

Identifying The scope of the resolution

The Rowland Hall debate team congregates in a small room connected to Shackelford’s office. National Speech and Debate Association student certificates cover one wall. It’s hard to miss the big trophy sitting on a file cabinet that proudly commemorates Rowland Hall as 2020-2021 1A-3A state debate champions. It will be accompanied by another after the team successfully defended its title earlier this month.

(Rowland Hall speech and debate team) The Rowland Hall high school speech and debate team takes first place at the Utah 1A-3A state debate tournament in March 2022.

Gathered around a table in the squad room, a handful of policy debaters let out a collective groan when asked about their initial reaction to learning they would spend the whole year researching and arguing about water resources. However, after students dove into the subject, their attitudes began to change.

“Living in a state that suffers drought or suffers pollution,” Rowland Hall policy debater Layla Hijjawi said, “I think it forced us to be a lot more nuanced in how we approached this topic and also forced us to recognize how it applied within our own lives.”

The majority of Utah is desert. Why are we growing incredibly water-intensive crops?

Through in-depth research on water policy and practices, students essentially become mini-experts on the topic. Policy debate students are discussing the same issues Utah legislators have spent decades grappling with.

As Hijjawi assembled copious loads of research, she noticed Utah’s role in the evidence pertaining to water consumption.

“Half of the examples were about the Great Salt Lake and Utah droughts and how in 50 years we are going to have a completely unsustainable amount of water for our growing population,” Hijjawi pointed out. “The majority of Utah is desert. Why are we growing incredibly water-intensive crops?”

Additionally, the freedom of policy debate grants students the opportunity to explore ideas outside of traditional policy making. One purpose of debate is to challenge mainstream thinking by identifying unique angles of argumentation.

For Rowland Hall policy debater Aileen Robles, the topic opened her eyes to how water policy often leaves Indigenous communities out of the conversation. Prior to the topic, Robles says the Indigenous connection to water is something she “didn’t even think about.”

“Just understanding how we interact with Indigenous people and how water rights are really important to them,” she said, “and I feel like I was kind of shortsighted in that.”

(

(Rachel Rydalch | The Salt Lake Tribune) Speech and Debate team member Cleo Shaw, practices the policy event in class at West High School on Friday, March 18, 2022.

To Cleo Shaw, a state policy debate co-champion and a junior at West High School, the most interesting aspect of policy debate is the abundance of available research “about actual productive solutions that we could be taking” to help solve “the water resource crisis or droughts or groundwater depletion.”

“It’s not like research doesn’t exist and that we can’t solve things,” she said, “it’s that we refuse to.”

Water solutions from the next generation

At the Utah 5A state debate tournament in Tooele County this month, Salem Hills High School policy debate partners Sahaja Rutledge and Tate Roberts were ready to put a year’s worth of work to the test.

Instead of putting all the pressure on the federal government to solve the water crisis, they toyed with dispersing responsibility.

When it comes to toxic algae blooms, to which Utah is no stranger, Roberts found evidence that proposed consulting NASA as part of the answer “because NASA has access to a lot of information about data and oceans and climate change.”

(Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune) Tate Roberts, member of the Salem Hills High School debate team, at the 5A state tournament at Stansbury High School in Stansbury Park on Friday, March 11, 2022.

Specifically, “NASA is keeping track of algae blooms so they don’t make dead spots that are just going to kill fish” Roberts said, stating NASA pinpointed Utah Lake as an example of where toxic algae blooms are negatively affecting biodiversity and the economy.

An argument Rutledge runs is requiring the federal government to create more federally or state-protected marine areas to preserve ecosystems, like fish populations, threatened by climate change and over exploitation of resources.

(Trent Nelson | The Salt Lake Tribune) Sahaja Rutledge, member of the Salem Hills High School debate team, at the 5A state tournament at Stansbury High School in Stansbury Park on Friday, March 11, 2022.

But debate taught her it’s not that simple.

“Private companies want access to those waters or farmers want agricultural water,” Rutledge noted. “But at some point, there’s going to come a time where it [protection of water resources] are either going to happen or it never will, and the species dies.”

In the halls of West High School, policy debater Ishan Sharma, also a state co-champion, sees cloud seeding, the man-made act of altering weather patterns to create more rain and snowfall, as a possible solution to reduce the footprint of climate change.

Cloud seeding promotes “the idea that we shouldn’t focus on solving for climate change, but mitigating the impact of it while other people figure out a solution to it,” Sharma said, highlighting a successful study of the method out of Idaho.

Rachel Rydalch | The Salt Lake Tribune) Ishan Sharma practices the policy debate event with his teammates at West High School on Friday, March 18, 2022.

But most of all, Sharma finds debate rewarding, even if he and his debate partner lose their match.

“It’s just really fun to meet people from other schools,” he said, “and have intellectual conversations with them for two hours-plus.”

‘say something that means something’

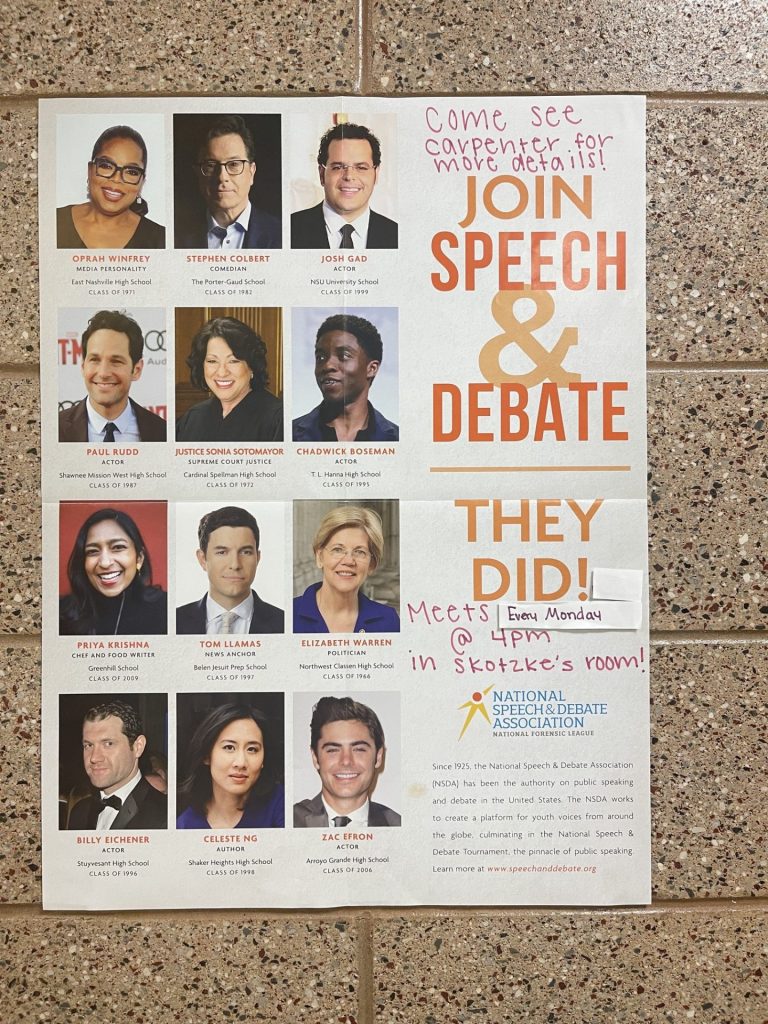

A poster hanging in the hallway of Stansbury High School showcases American icons who participated in speech and debate like Oprah Winfrey, comedian Stephen Colbert and even High School Musical star Zac Efron.

In big bold letters, the sign reads: “Join speech & debate. They did!”

I would like to see them enter the public arena where they can alter and change the world we live in.

Susan M Raymond, the head debate coach of West High School team that recently took first place at the 6A state tournemnet, believes the students who participate in speech and debate are the next leaders and influencers. Their faces will soon enough be plastered on a poster as a way to entice future debaters.

“I would like to see them enter the public arena where they can alter and change the world we live in,” she said. “That’s what I want.“

Despite being a labor-intensive and time-consuming activity, Mike Shackelford, the Rowland Hall debate coach, says debate is sustained by the “inspirational people who are self-sacrificing” and those who have “a shared respect for intellectual curiosity.”

“We compete in debate, but it never felt like we were adversaries,” Shackelford emphasized, “it felt like we were just going to the same academic party.”

And while this academic party is about to close for the season, policy debaters are leaving the podium with more smarts about the most pressing problem facing Utah for generations to come.

“You can’t stand up and say water conservation isn’t necessary—because it is. We can tell, especially when you can’t refute evidence and statistics,” Sahaja Rutledge, a policy debater at Salem Hills, said. “Debate has taught me to say something that means something.”