Nicknamed “Happy Valley,” Utah County is known for the gleaming tech offices of Silicon Slopes and the tidy campuses of Brigham Young and Utah Valley universities.

But scores of unsheltered people live in the county, which — despite having the state’s second largest population — doesn’t have a single homeless shelter.

If you’d like to support journalism like this, click here.

With no emergency shelter where people can sleep overnight, providers try to offer transitional housing or permanent places to live — or pay for a few nights in hotels, for those who need immediate help.

But this safety net has holes. People who fall through them can end up sleeping outdoors, often choosing hidden spots to avoid detection by police and the community.

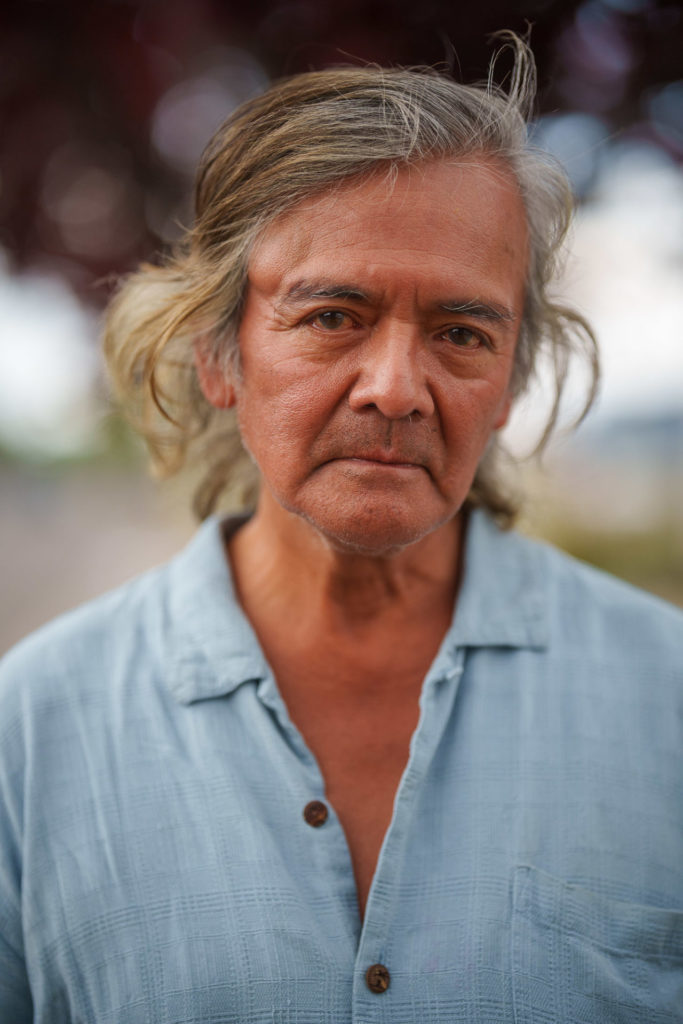

Kevin Roy Evans, 61, sleeps on even the coldest of nights without a tent, in an effort to avoid receiving a camping ticket from the Provo Police Department.

“I prefer if I got a warm sleeping bag, you know, I just lay it in the dirt,” he said. But frostbite has been getting to his fingers recently, he said, even on warmer spring evenings.

Kevin has spent many nights over the past few weeks behind this dumpster in Provo. He sleeps on the ground with the lid propped open over him, to protect him from rain or snow.

“You know, the little bit of shelter goes a long ways with me,” he said.

But after receiving some pushback from a nearby business, Kevin recently moved to a different dumpster enclosure to spend the night.

“It’s a good little area to hide,” he said of the new spot.

People experiencing homelessness have become less visible since Provo passed its camping ordinance in 2017, many homeless advocates agree. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t there.

To avoid police, they’ve simply moved into surrounding cities, the canyons and harder-to-find places within Provo.

“You can’t find them when they don’t want to be found,” said advocate Sandra Bennett. With the Genesis Project, a nondenominational church in Provo, she helps distribute supplies each week to people experiencing homelessness.

“They’re basically invisible,” she said.

Some people sleep in their cars — including Jackie Davidson, 75, who said she has three or four spots that she moves her car between to avoid suspicion. Others couch-surf or stay overnight in a 24-hour laundromat.

Edgar Gago, 66, recently found refuge for a night on a bench on University Avenue, where he said he was only able to sleep three hours. But the police didn’t bother him there, he said, because he slept upright and “didn’t break the rules” against camping.

Many people experiencing homelessness hesitate to divulge where they sleep in Utah County, out of fear of police crackdowns. But outreach workers with Wasatch Behavioral Health say they have places they typically check, including underneath the freeway or bridges, in little-frequented alleys and behind buildings.

Outreach workers say they have found people sleeping in these Provo spots:

Advocates disagree about whether Utah County needs an emergency overnight shelter.

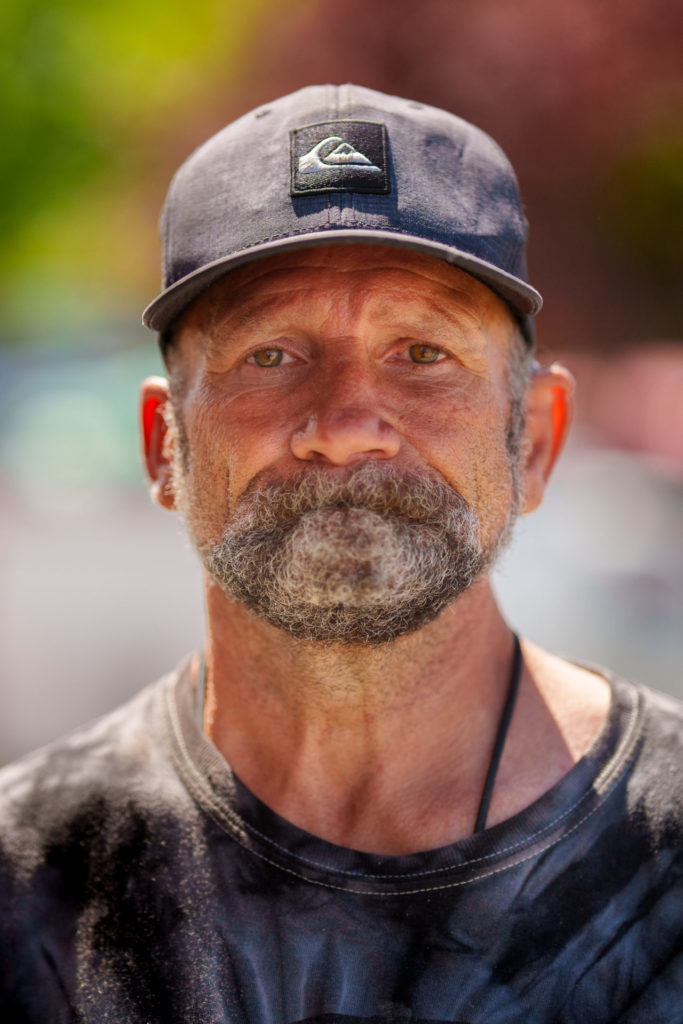

But at least some people experiencing homelessness want one — including Danny Herring, 52, who said he would go to a shelter, at least “for a while.”

“You can’t sleep out at night,” he said. “You can’t panhandle. You can’t hardly do anything. So all the homeless people around here in Provo and stuff, they have a really hard time getting by.”