They would have started the morning with inspections of their cleaning; they would end their day with bedtime after taps.

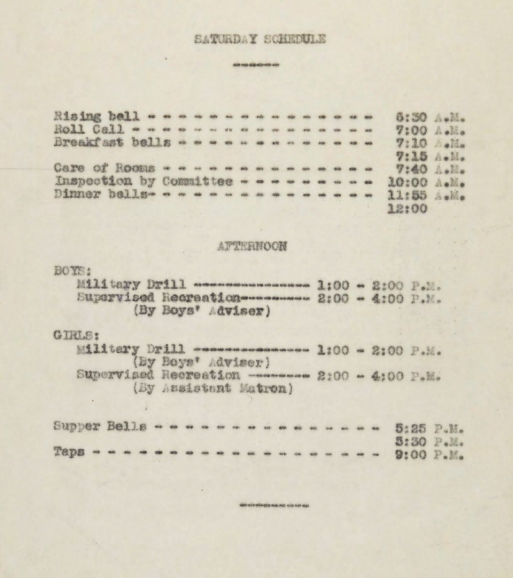

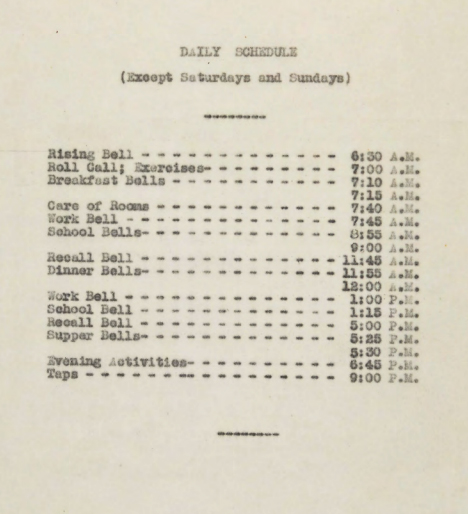

No matter the day, they were up at 6:30 a.m., with every hour — sometimes in increments as small as five minutes — plotted out in a strict bell schedule.

Two years earlier, the influential Meriam Report had criticized the rigidity of the country’s federal Indian boarding schools, from the military drilling that was “largely obsolete even in Army camps” to harmful punishments to the “routinization” that was “the one method used for everything.”

“If there were any real knowledge of how human beings are developed through their behavior,” the report said, “we should not have in the Indian boarding schools the mass movements from dormitory to dining room, from dining room to classroom, from classroom back again, all completely controlled by external authority.”

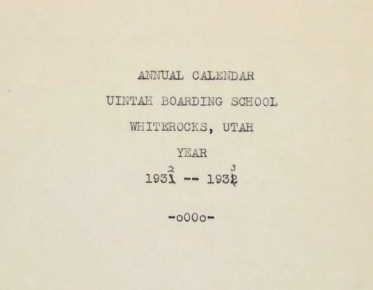

That was precisely the environment in the Whiterocks boarding in the 1930s, according to annual calendars with bell schedules obtained from the National Archives at Denver by The Salt Lake Tribune.

Julius “Chunky” Murray Jr., who attended the school in the 1940s, said that regimented approach endured.

“They had a bell to ring to get up. They had a bell to ring for breakfast. They had a bell when you were through eating,” he told an interviewer for a 1980s oral history project. “They had a bell when you went to school. They had a bell during recesses — they had a bell when school was out. Eh, you lived by the bell. We had no freedom.”

The Tribune obtained calendars for the 1930-31 school year, the 1932-33 school year, and a special report created by Girls’ Adviser Grace E. Shively for the 1935-36 school year, which includes photos and a more personal look at the girl’s lives. See the index for student names in that report here.

1930-31 school year: “The school is going to be first at all times.”

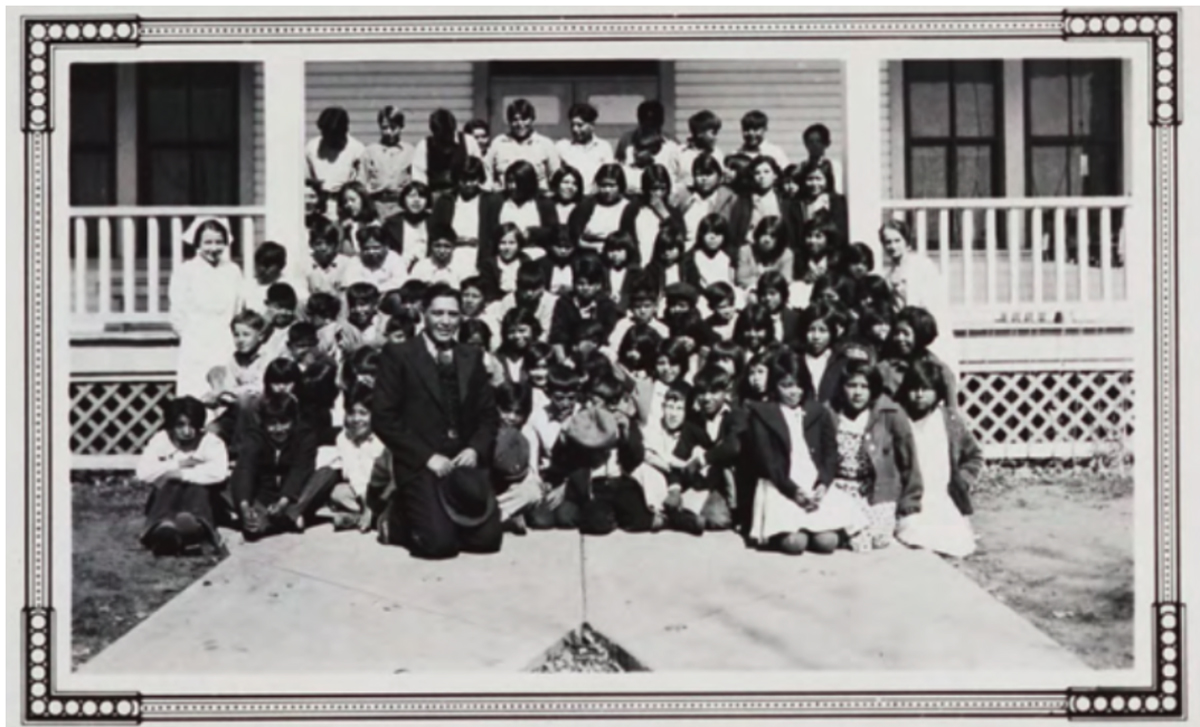

The boarding school seemed as stern with its employees as it was with students. They needed permission to leave the school; they were each expected to serve as a “personal example” and “avoid small personal differences.” General rules warned: “Remember that the school is going to be first at all times, and if you do not wish to co-operate, the best plan will be to leave.”

The school continued its stance from earlier years that the children’s contact with their families must be limited: “Frequent visits home are harmful to school interests and morale. As a privilege, leave to pupils will be granted only as a mark of special merit, or in case of serious family sickness.”

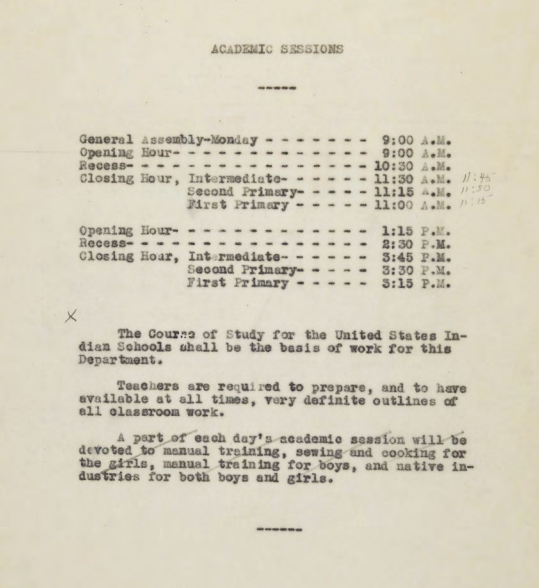

It also continued arranging work details. The schedule for academic learning included this note: “A part of each day’s academic session will be devoted to manual training, sewing and cooking for the girls, manual training for boys, and native industries for both boys and girls.”

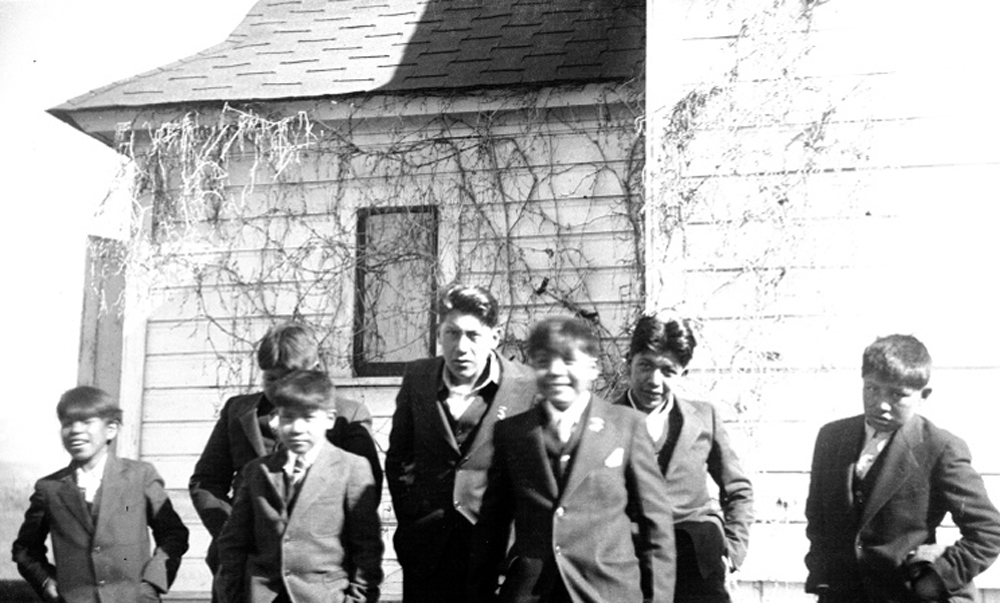

1932-33 school year: “They finally did away with the military.”

The school calendar for the 1932-1933 school year was created by handwriting updates over a copy of the 1931-1932 calendar, providing a record of both years.

The Saturday military drills were replaced by calisthenics, which were also part of each day’s school session, “out of doors in all but the most inclement weather.”

Nancy Pawwinnee, who attended the school then, remembered the change.

“When I first went up there … it was kind of like a military school, Whiterocks was,” she told an oral history interviewer. “We had to drill, we wore uniforms, but that was just for the one year and my first year up there … We had to drill, we had to march around, we had the captain that cracked the whip, and I mean cracked the whip too.

“But then they kind of eased up on that. They finally did away with the military type of thing.”

The children were given time to practice traditional arts, such as beading and weaving. Those afternoon sessions, however, remained in a rotation with work, such as doing laundry. And the detailed scheduling of their days was little changed from 1930.

1935-1936 Report of Girls’ Adviser: “As homelike as possible.”

For the 46 girls who attended this school year, Girls’ Adviser Grace E. Shively wrote, “We endeavored to make Minnetaka Hall as homelike as possible. The girls were given considerable freedom and as a rule they did not take unfair advantage of their liberty.”

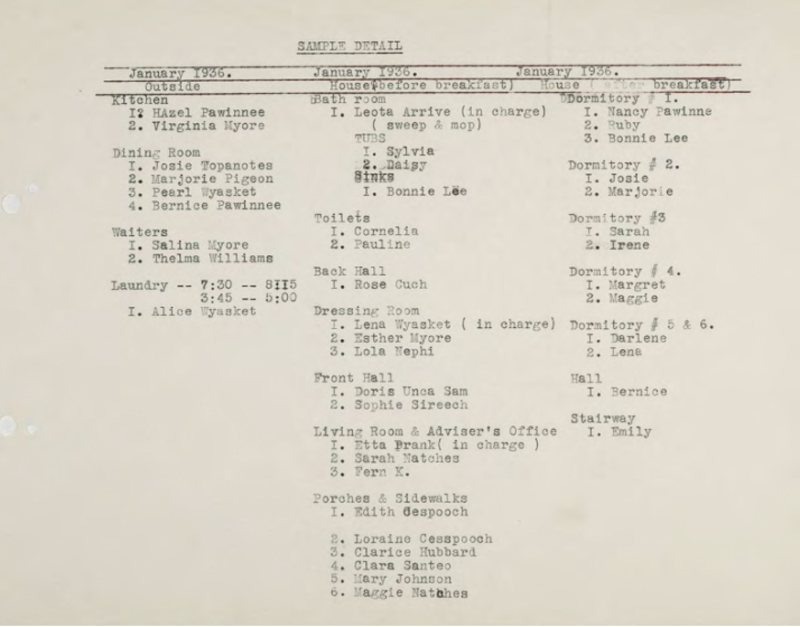

The calendar shows such liberty remained carefully scheduled. Shively also described the continuing work details, providing a January 1936 example of girls’ duties that included the names of the students assigned “outside” or as “house girls.”

“Saturday was special ‘clean up’ day,” she wrote. “All of the woodwork was washed, floors waxed, porches and sidewalks scrubbed and yard raked on this day. When the Saturday cleaning was finished the girls were at liberty to do anything for themselves such as mending, person[a]l washing, etc.”

An activity calendar showed the children were taken on picnics, shopping outings in Roosevelt and occasional field trips, to place like the nearby fish hatchery and Dinosaur National Monument.

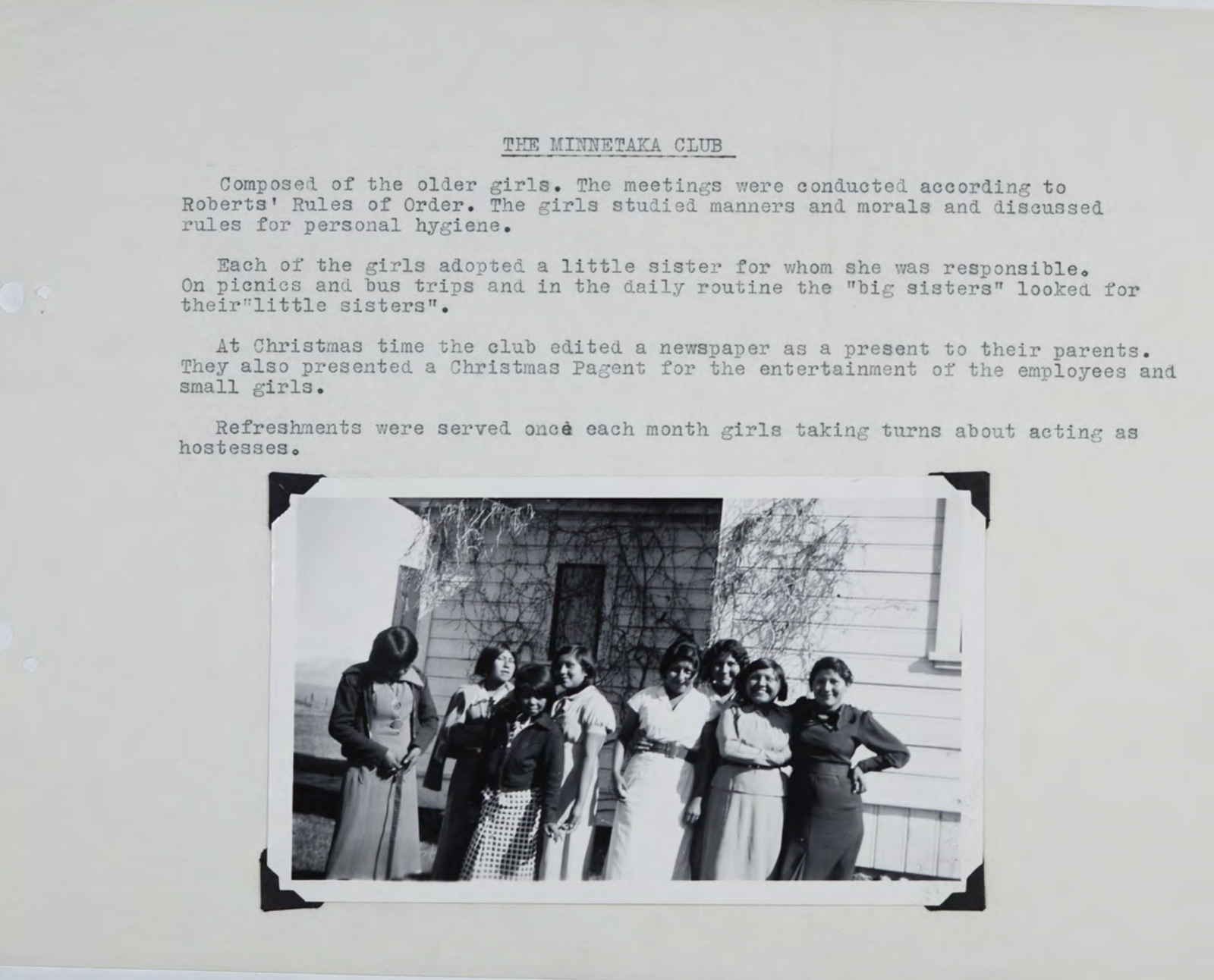

The girls participated in Girl Scouts and had clubs within the school — the smaller girls studied English in their meetings, and the older girls learned manners in theirs.

Sickness among girls at the Uintah Boarding School seemed common.

“At no time during the year were there less than two girls sick in bed,” Shively wrote, and then seemed to refer to her work caring for the girls in the third person.

“Since there was no isolation room caring for them was made rather difficult. However, we managed very nicely by making beds in the adviser’s office when only two or three were ill,” she continued. “By doing this stair climbing was not necessary and the sick were near the advisers quarters thereby making it easier for the adviser to care for them. Since there was no school nurse the adviser did all of the bed side nursing.”

There were two epidemics of scarlet fever, “one in November and part of December and the other in January and February,” she noted.

“During these epidemics the play room was converted into an isolation ward and quarantined. The adviser cared for the children both day and night, prepared their trays, boiled their dishes and cleaned the ward. The doctor did not allow her to mingle with the well children hence most of the routine work was done by the assistant.”

While some girls remained ill with scarlet fever, she continued, “several girls came down with the mumps and were isolated in the adviser’s office. Hence for a period of several weeks the adviser had from ten to twelve children to nurse day and night.”

With the disruptions caused by changes in personnel and the epidemics, Shively concluded, “The girls have been most patient and helpful during an exceedingly difficult year.”

Read the 1935-1936 Report of Girls’ Adviser

Index for 1935-1936 Report of Girls’ Adviser

Student names appear in on Page 21, in a sample of work details.

Column one

Hazel Pawinnee

Virginia Myore

Josie Topanotes, later Josie

Marjorie Pigeon, later Marjorie

Pearl Wyasket

Bernice Pawinnee, later Bernice

Salina Myore

Thelma Williams

Alice Wyasket

Column two

Leota Arrive

Sylvia

Daisy

Bonnie Lee

Cornelia

Pauline

Rose Cuch

Lena Wyasket, later Lena

Esther Myore

Lola Nephi

Doris Unca Sam

Sophie Sireech

Etta Brank or Prank

Sarah Natches, later Sarah

Fern K.

Edith Cesspooch

Loraine Cesspooch

Clarice Hubbard

Clara Santeo

Mary Johnson

Maggie Natches, later Maggie

Column three

Nancy Pawinnee

Ruby

Bonnie Lee

Josie

Marjorie

Sarah

Irene

Margret

Maggie

Darlene

Lena

Bernice

Emily