Reporter Courtney Tanner examined hundreds of pages of records, from the boarding school era to the transition to public schools to recent grades, ACT scores and graduation rates in the Uintah and Duchesne school districts.

Those districts split the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in eastern Utah and serve about 800 Native students — largely Utes — between them.

Ute kids singularly fall behind in every metric and have for decades.

“There was never really a commitment to educate our kids,” said Forrest Cuch, a former education leader for the tribe. “Otherwise, we wouldn’t be seeing this pattern for so long.”

Here’s a breakdown of each part of The Tribune’s series and where to read them:

Part 1: The Ute Tribe’s kids have been failed by the public school system more than any other students in Utah

Ute kids see the lowest test scores and drop out of school at the highest rates in the state. Jayme Leyba, who oversees underrepresented student populations for the Uintah School District, acknowledged the shortcomings. “I wouldn’t blame people,” he said, “for being frustrated.” Duchesne County School District said it is “aware of the gaps in our system.”

The Ute Tribe’s kids have been failed by the public school system more than any other students in Utah.Part 2: The warning signs were clear and repeated

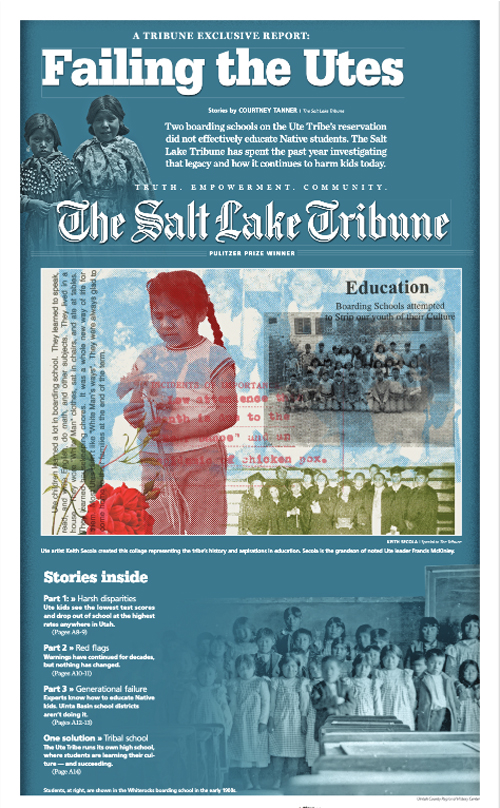

Ute students started being left behind by the two boarding schools on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation — where white superintendents focused on labor over academics. Ute children later arrived less prepared in public schools, once they were allowed to attend, and were not able to catch up. One former tribal education leader thinks the failures in Utah’s education system are intentional.

Utah’s education system is failing Ute kids, and a former tribal education leader thinks that’s intentional.Part 3: Experts know how to educate Native kids. Uinta Basin school districts aren’t doing it.

For the more than 70 years that Ute students have been languishing in public schools, leaders have also known what would help them succeed. It’s a paradox that Bryan Brayboy, a member of the Lumbee Tribe and director of Arizona State University’s Center for Indian Education, finds infuriating.

“Sometimes we forget that what we’re calling for isn’t actually new,” said Brayboy, who is also a professor of Indigenous education. “There’s a long history, a long list of studies that show if you can use culture in the classroom, that students can do really well.”

The Ute Tribe is trying to make up for the state’s education shortcomings, but resources are limited.One solution: A public tribal charter school

The Ute Tribe runs its own high school, where students are learning their culture — and succeeding.