On this page:

Muse Harris, in 1968: “You just go to school and finish up.”

Connor Chapoose, in 1960: Pursuing “the knowledge of the white people.”

Ina Lou Chapoose and Marrietta Reed, in 1969: A look at Head Start

Hal Albert Daniels Sr., Hal Albert Daniels Jr., in 1967: Sent to Whiterocks “pretty young.”

Ethel Daniels Kolb, in 1968: “My, how sad I was.”

Cecelia Panteloon Lambeth, in 1968: “They … just let them pass.”

Linda Pawwannie, Clarice Pawwannie, in 1968: “How our people lived.”

Marietta Reed, in 1970: “We have lost true identity.”

Joseph Pinnecoose, in 1970: “I want to go where there’s Indians.”

Katherine Jenkins, 1970: “We really have to … help these kids.”

Glenna Jenks, 1970: “Most of all, concentrate on your work.”

Margaret Eberly, in 1967: “Most of them hate history and I don’t blame them.”

Larry McCook, in 1986: “They didn't even try to teach us.”

Francis McKinley, 1980s: “It was rather harsh.”Julius “Chunky” Murray, Jr., 1980s: “Hated it. You're a prisoner in the school.”

Ethel Grant, in 1982: “I talked mostly Ute language”

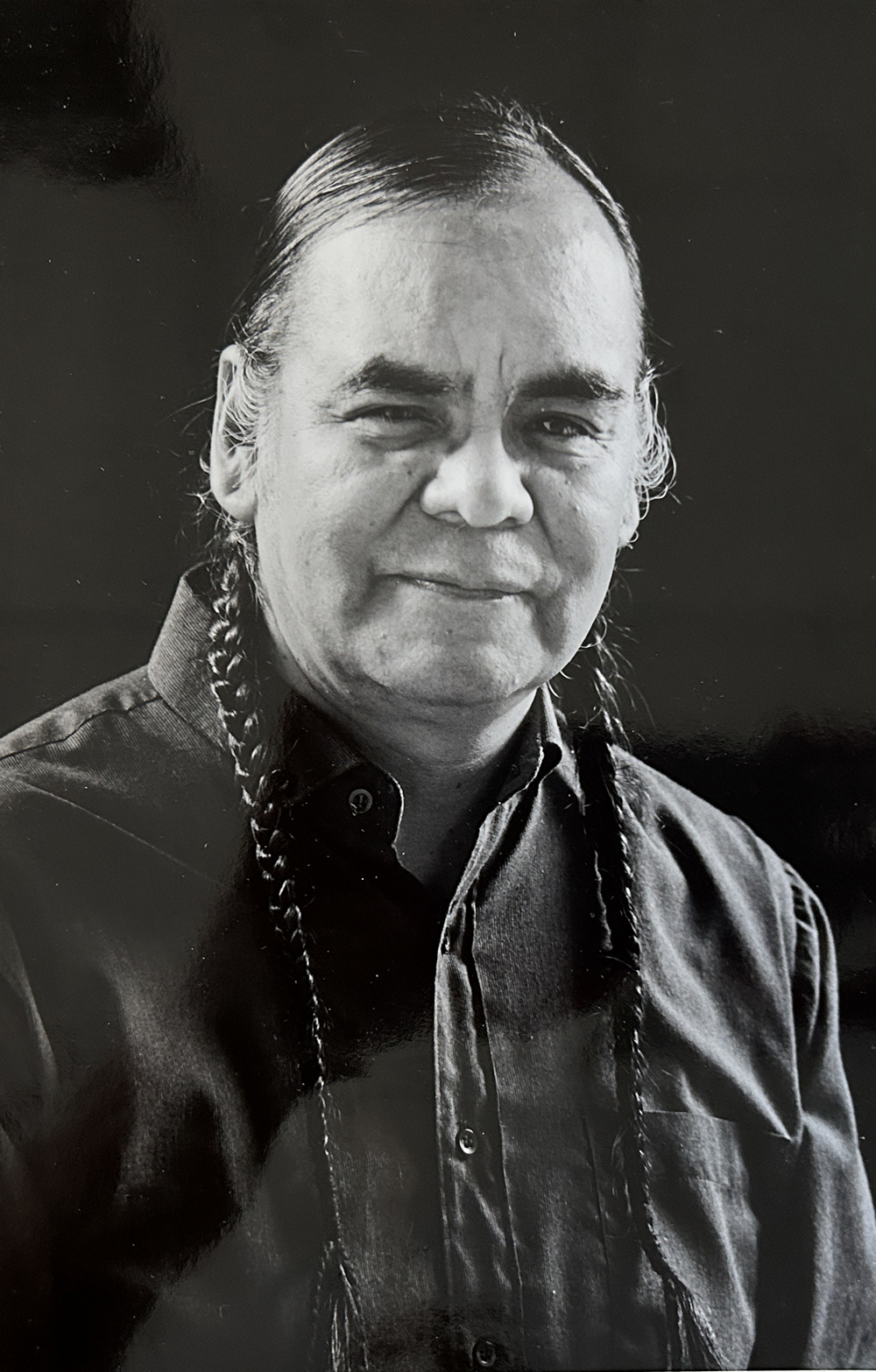

Clifford Duncan, in 1982: “The teacher catches you speaking Indian, that was it.”

Nancy Pawwinnee, in 1983: “You learned to clean house.”

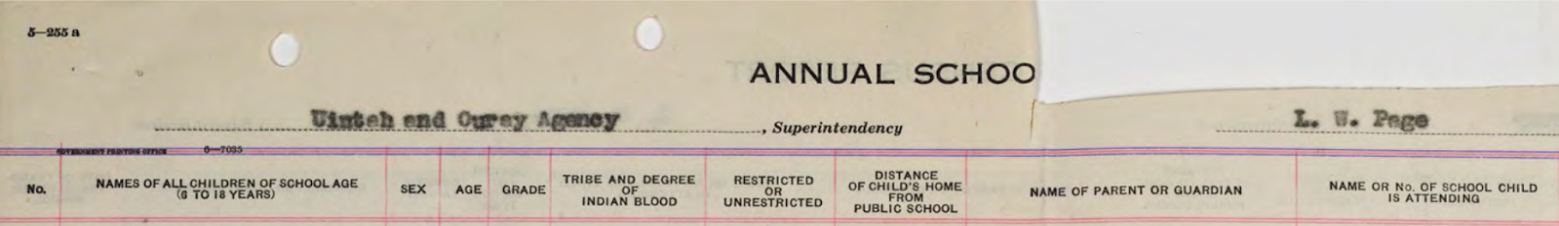

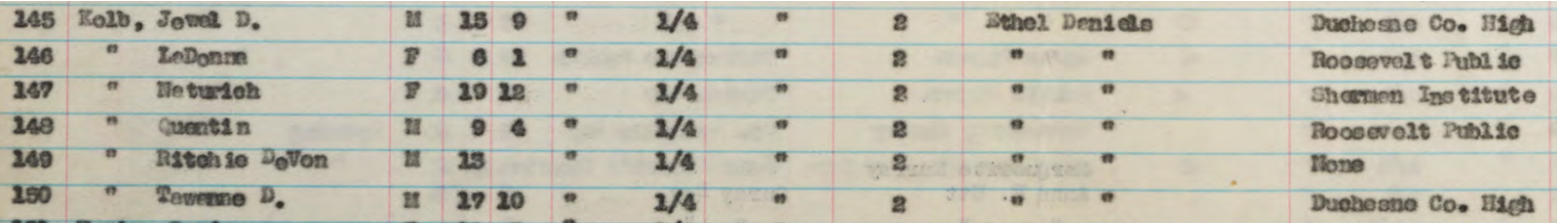

Quentin France Kolb, in 1997: “I certainly would not wish it on anyone.”

By Courtney Tanner and Sheila R. McCann

The Salt Lake Tribune

Most of the time, he and his brother would dig holes under the fences that surrounded the boarding school in the small town of Whiterocks, on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation.

“We’d take off,” he recounted. “We’d make for that hole, and we’d walk or run or bum a ride, anyway we could get home from there.”

It happened again and again. One April, he said, his parents — who were forced to enroll their kids — took the brothers back to the school. “That night we was back home,” Harris said. “We never stayed.”

Harris, who was Ute and born in the 1890s, also went to the second boarding school that operated on the reservation, in nearby Randlett, for a short time before it closed.

He spoke to an interviewer in 1968 as part of the Doris Duke American Indian Oral History Program; such interviews are some of the only accounts of what students experienced, in their own words, in the Uintah boarding school in Whiterocks and the Ouray boarding school in Randlett.

Here are excerpts from many of the Ute oral histories in Utah; find more information below about the collections and where to find them. The name spellings used here are as they appear in the transcripts.

Doris Duke Collection

Muse Harris

Box 8, No. 195

(also Box 9, No. 282)

Muse Harris talks about how he “didn’t take too much schooling” at the federal boarding schools at Whiterocks and Randlett. He was transferred to a public school in Vernal, and finished classes there through the eighth grade. He said he regretted not learning as much as he wanted to.

Harris recounted: “If I had any more grades why I wouldn’t been here now. I might’ve been in the White House. Well, I didn’t learn much, but I’m a kind of funny, I can tell a story and remember pretty good, but by jimminey, I’m not right up qualified like I should be. I know now what I should’a done. But I’ll tell ‘ya, all you kids, by jimminey, if you want to make good, you just go to school and finish up. Don’t quit just as soon as you pass on from the eighth grade.”

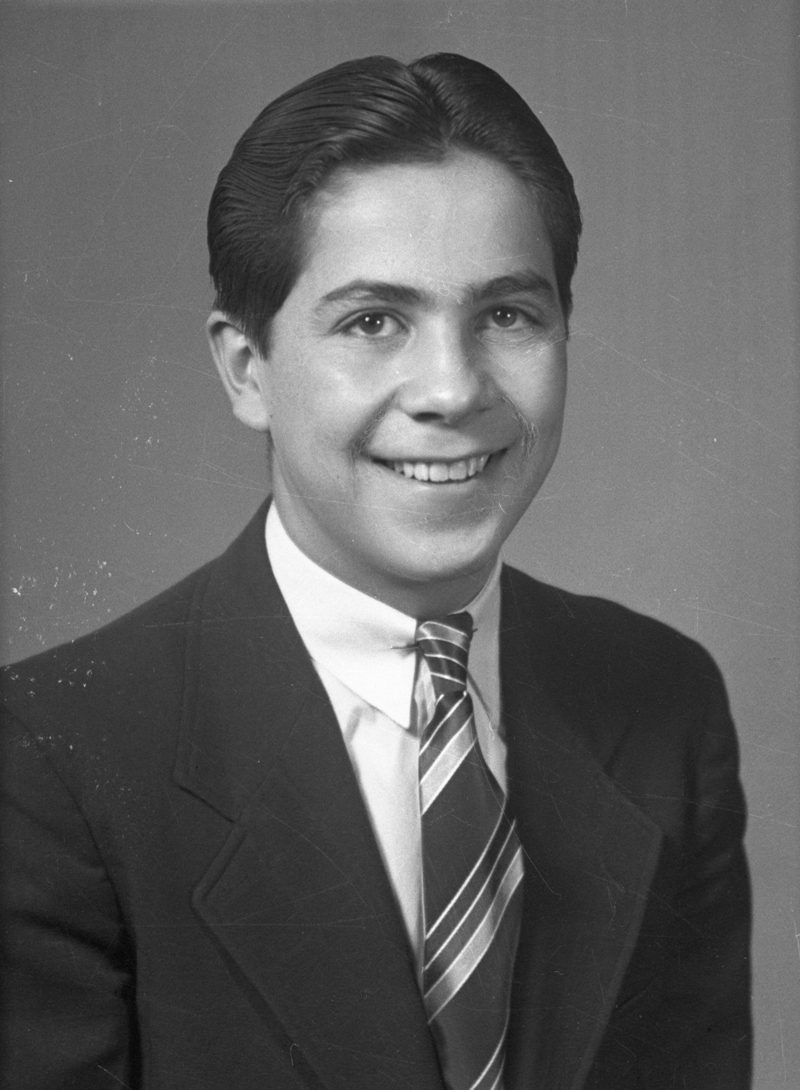

“The knowledge of the white people.”

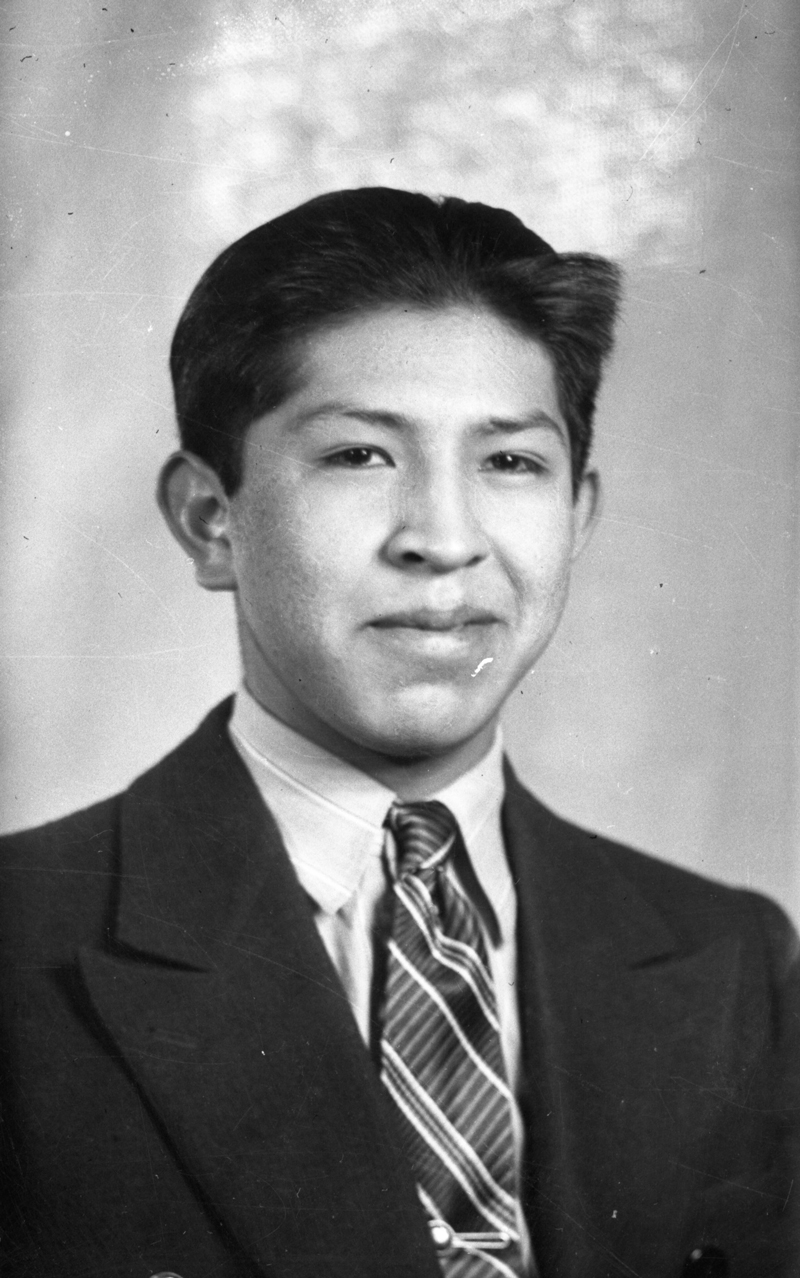

Conner Chapoose

Box 1, No. 1-11 (5, 7, 8 include discussion of boarding schools)

Interviewed in 1960, Connor Chapoose described the transition for Ute kids from the boarding school at Whiterocks, which closed in 1952, to the public schools in the Uinta Basin.

Families in the tribe, he said, “pretty much faced that we have to go to school, that the law meant for us to go to school and to acquire, to get to know the knowledge of the white people.”

ut the public school districts didn’t effectively serve Native children. Chapoose said Ute students often sat in the back of the class and got called “dumb” by their white peers. White parents, he recalled, also told their kids: “Don’t you play with that filthy Indian.”

The result, he felt, was that Ute kids didn’t do as well in school they should have, and could have.

A look at Head Start

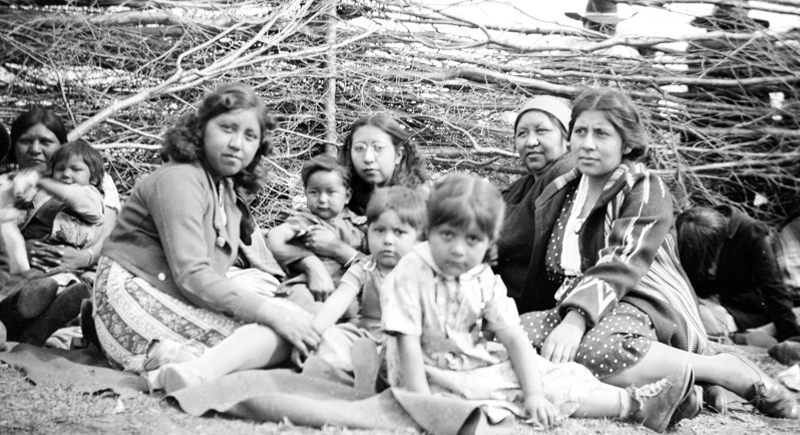

Ina Lou Chapoose and Marrietta Reed

Box 4, No. 65

Ina Lou Chapoose and Marrietta Reed, (sister and daughter of Connor Chapoose) worked at the Head Start program to help Ute kids learn better in school. They describe having story time, songs and crafts that worked well for Native students. About 15 were enrolled at the time, in 1969.

Chapoose said Ute parents “have now come to realize how important education is to our children.”

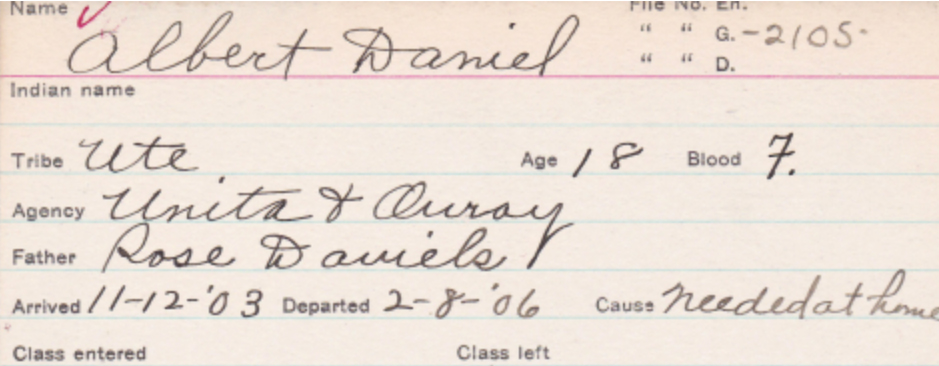

“I was pretty young.”

Hal Albert Daniels Sr. and Hal Albert Daniels Jr.

Box 4, No. 66

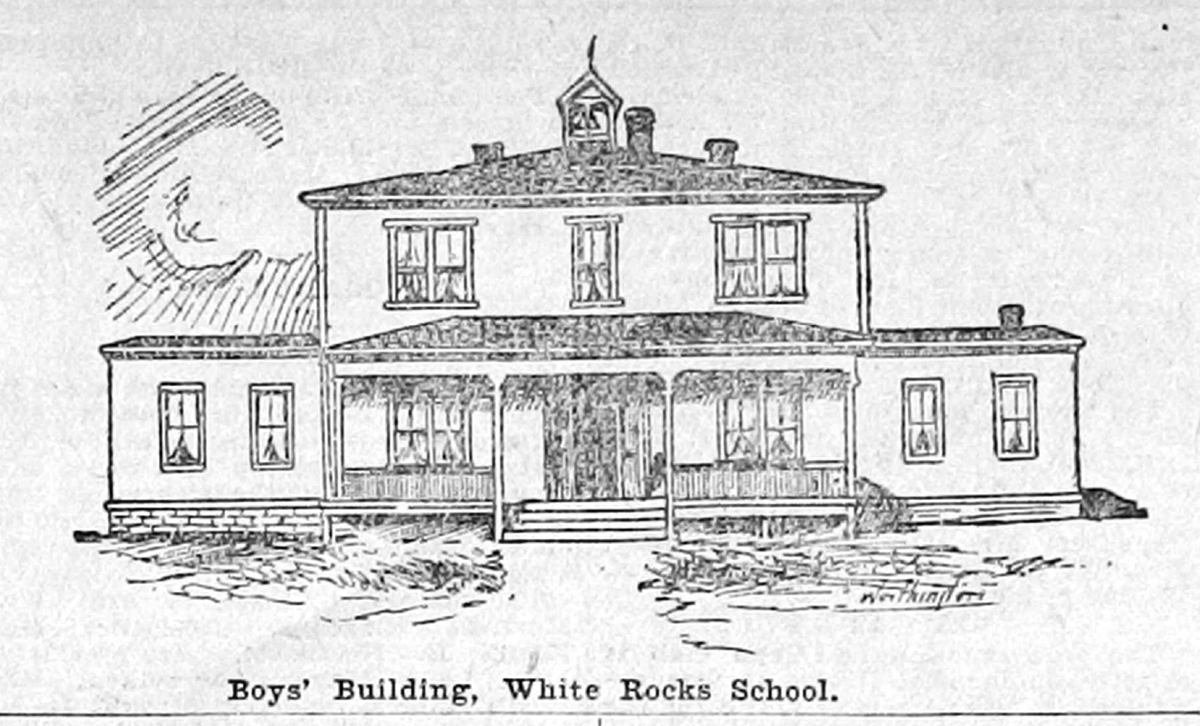

Hal Albert Daniels Sr. attended the boarding school at Whiterocks, starting when he was 5 years old.

“I was pretty young,” he said in the 1967 interview. “… They just built them great big buildings they used to have up there — the boys’ dormitory and the girls’ dormitory, then the boys’ room.

He then went to a boarding school in Grand Junction, Colorado, for a year in 1893. And after that, he was transferred to the Carlisle Industrial Boarding School in Pennsylvania.

“And you got a lot of discipline there,” he said. “They had a lot of it.”

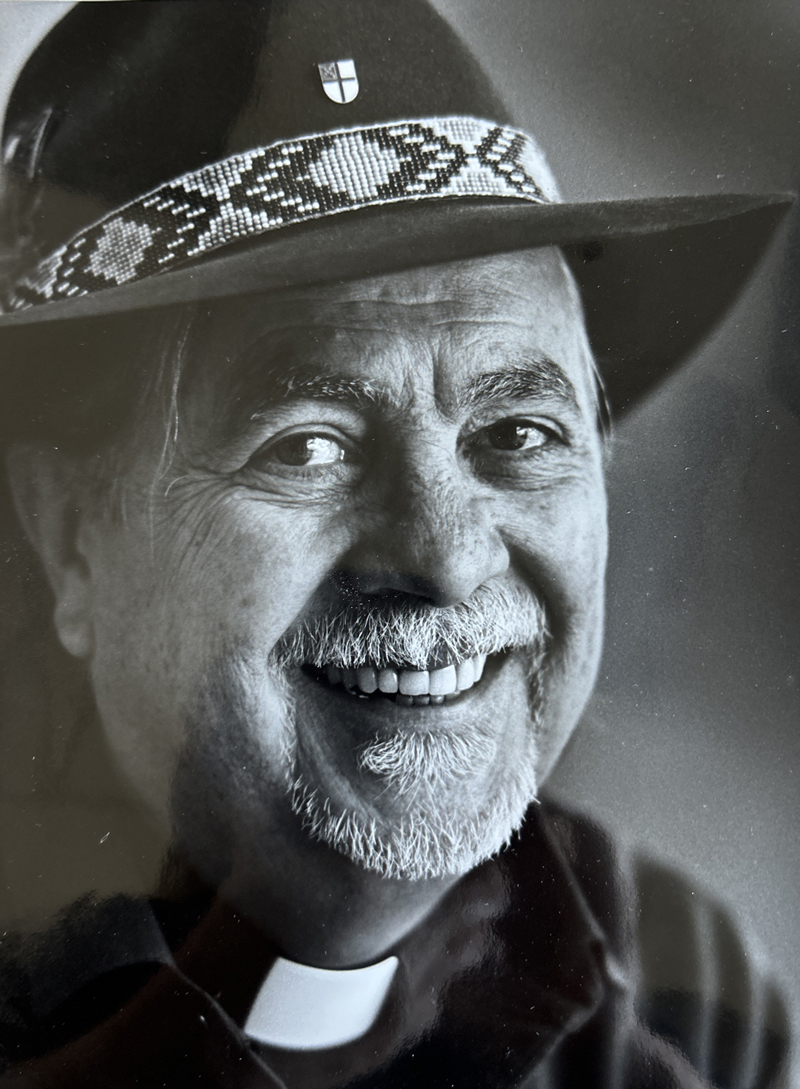

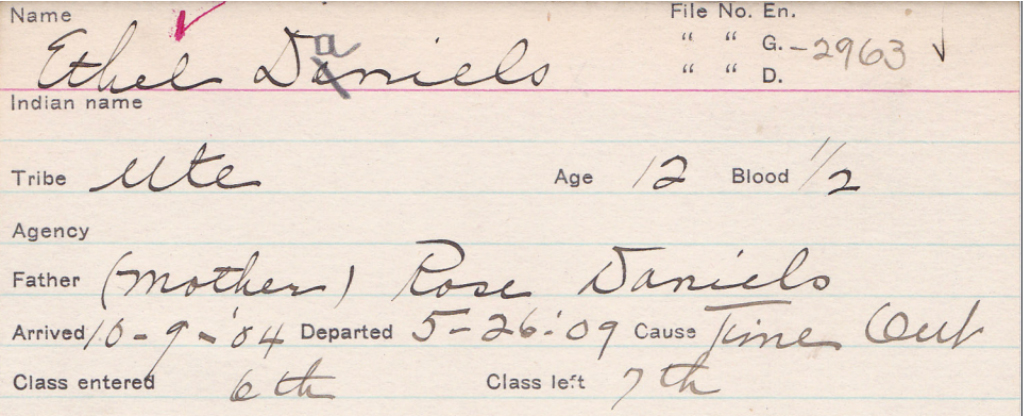

“My, how sad I was.”

Ethel Daniels Kolb

Box 8, No. 229

Ethel Daniels Kolb said she went to the Whiterocks school for a short time before also being transferred to Carlisle.

“A wagon picked me up at the farm, and we went as far as Wells Station, between Myton and Nine Mile,” she said. “My, how sad I was thinking of Mother and Mentora alone on the big farm, and I wouldn’t see them again for five years. You know we had to stay that long when we went away to school.”

The first three weeks at Carlisle, she said, were the worst. “I cried a lot and wanted to go home so badly, but of course I couldn’t,” she said. She mentioned learning to sew there. She also noted other Ute students there with her: Dick Quip, Laura Taylor, Lottie Sireech, Robert Ouray and Fred Mart. Sireech died at Carlisle.

“Boarding schools are fine, when you get over being homesick,” Kolb said in the 1968 interview. “I know we learned a lot and met lots of other people.”

“They … just let them pass.”

Cecelia Panteloon Lambeth

Box 11, No. 366

Cecelia Panteloon Lambeth in 1968 recalled attending Whiterocks and talked about her teachers there, all of whom she said were white. They included Mrs. Wapstock (sic), Mrs. Jones and Mrs. Phillips.

Lambeth said she attended school there through the fourth grade and then transferred to a school in Salt Lake City for a year. “That was the last time I ever went to school,” she said.

The interviewer asked Lambeth if her parents were resistant to sending her to school.

“They were just the old Indian type that didn’t, they didn’t have any education themselves, either, and they just didn’t, I guess they didn’t care whether we went to school or not,” Lambeth responded.

She noted her parents didn’t speak any English.

Lambeth also said she thinks the boarding schools, as well as the public schools, didn’t know how to teach Native kids.

“A lot of these Indian children down here went to school and they never learned anything, in fact, they, I guess the teachers didn’t like too much time with them,” she said. “They just, you know, just let them pass. I know some young men and women down there that went to as far as eleventh grade or on up, and they just, they can’t hardly read.”

But she said she considered education what the Utes needed most. “Yes, I think Indians have just as good a chance as a white person has, if they have the education and the training for the job,” Lambeth said.

“How our people lived.”

Linda Pawwannie and Clarice Pawwannie

Box 11, No. 371

In 1968, Clarice Pawwannie (sic) said she had heard about the mistreatment of Ute students by their teachers in the public schools, but her daughter, Linda, didn’t experience that.

Linda talked about attending Union High School and planning to go to college with her friends. But she said she would’ve liked to learn more about “how our people lived and stuff before” while she was in school.

“We have lost true identity.”

Marietta Reed

Box 11, No. 372

(also Box 17, No. 605)

Marietta Reed, who worked in the Head Start program, also said she wanted more Native curriculum in schools.

“I feel in a way we have lost true identity as Indians,” she said in 1970. “We were the first people that were to be here on this earth, as I have gathered. And I think it would mean a lot because in some way our young children have lost their identity as the Indian people.”

Reed said she was worried about youth no longer knowing about their culture.

“We should continue to teach our Indian children to speak the Ute Indian language,” she said. “And so many of our young people have forgotten. They have even forgotten how to talk it. Some of them don’t even know anything about Ute Indian people.”

She urged the Ute Tribe to work with the schools. Reed mentioned some Ute kids participating in the Latter-Day Saint Placement program, but she felt schools were a better place for them to learn.

She said there is still “the feeling that we are not quite welcome in the non-Indian society as of yet,” but she hoped it could be addressed through education.

“I want to go where there’s Indians.”

Joseph Pinnecoose

Box 17, No. 603

Joseph Pinnecoose was a Ute student in the public schools who later went on to attend Brigham Young University.

But his time at BYU was a challenge, he told an interviewer in 1970, and he flunked out. “It seemed that I couldn’t get any help all that time,” he said.

He said he wanted to try another college where there were more Native students like him.

“I want to go where there’s Indians,” Pinnecoose said. “I would like to go to a school in South Dakota, but I don’t know. It really makes me feel like being around Indians more, rather than being around with the Anglo.”

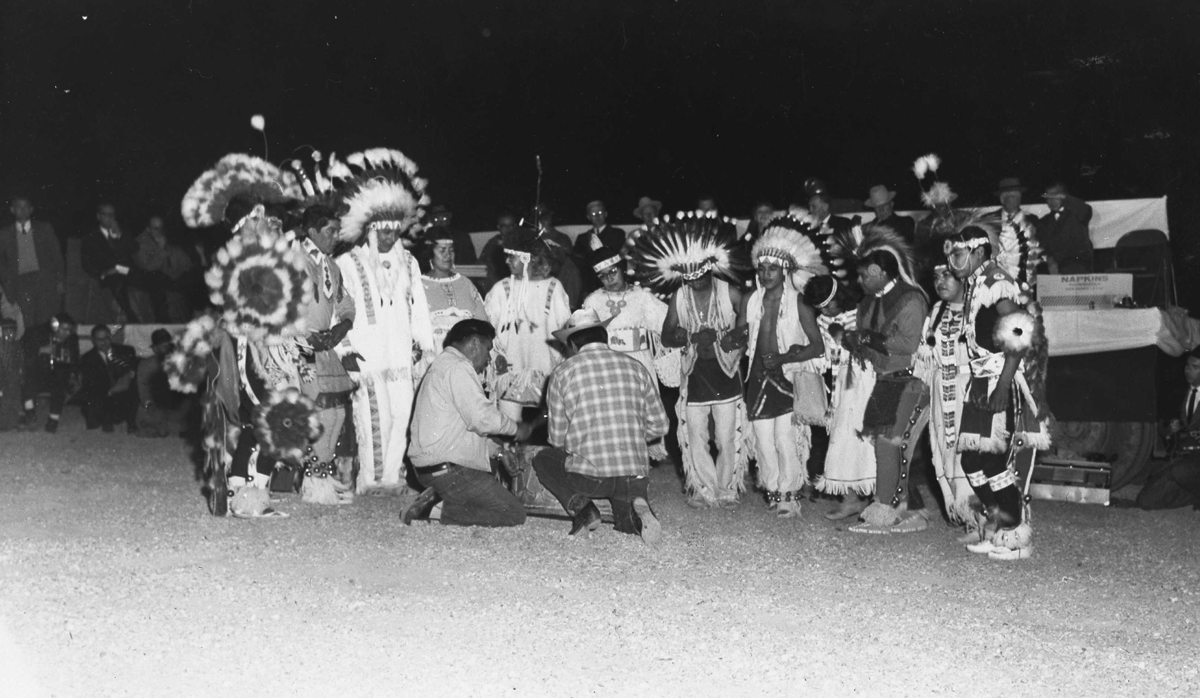

Pinnecoose also encouraged public K-12 schools in the Uinta Basin to teach Ute culture and history. But he said traditional songs and dances should be kept only within the tribe.

“We’re Indians, and we’re not going to share our culture, only to show it,” he said. “But we should keep our culture within us, not spread it all over the place among the white people.”

“We really have to … help these kids.”

Katherine Jenkins

Box 17, No. 606

Katherine Jenkins noted in her interview that she saw education improving for her kids in the public school system: “And I guess, this goes to show that we really have to put our efforts in ourselves to help these kids in every way we can, so that they can get better education than we did when we were little.”

“Most of all, concentrate on your work.”

Glenna Jenks

Box 17, No. 628, 629

Glenna Jenks talked about being an A student in public schools. She said it took hard work and diligence and propelled her to later win the title of Miss Utah Indian.

When the interviewer asked what advice she had for other Ute students, Jenks said: “Most of all concentrate on your work. No matter if people are picking on you or things like this. … No matter if your skin is one color or a different color. It’s just a matter of having faith within yourself. And you can do it.”

Jenks, who attended Brigham Young University, said she wanted to go to college so she could become a teacher and help Ute kids graduate.

Jenks said some Native children choose to go shoot pool instead of attending classes. “Maybe it is a type of inferiority that they have. I know sometimes I feel this,” she said.

She also mentioned a girl she went to school with, who sat at the back of the class and rarely participated. “And today I look at her, she’s adjusted sort of, she accepts her role as being a ‘D’ student, she accepts her role as being that inferior type of person.”

“The whole thing is so negative”

Margaret Eberly

Box 3 No. 57

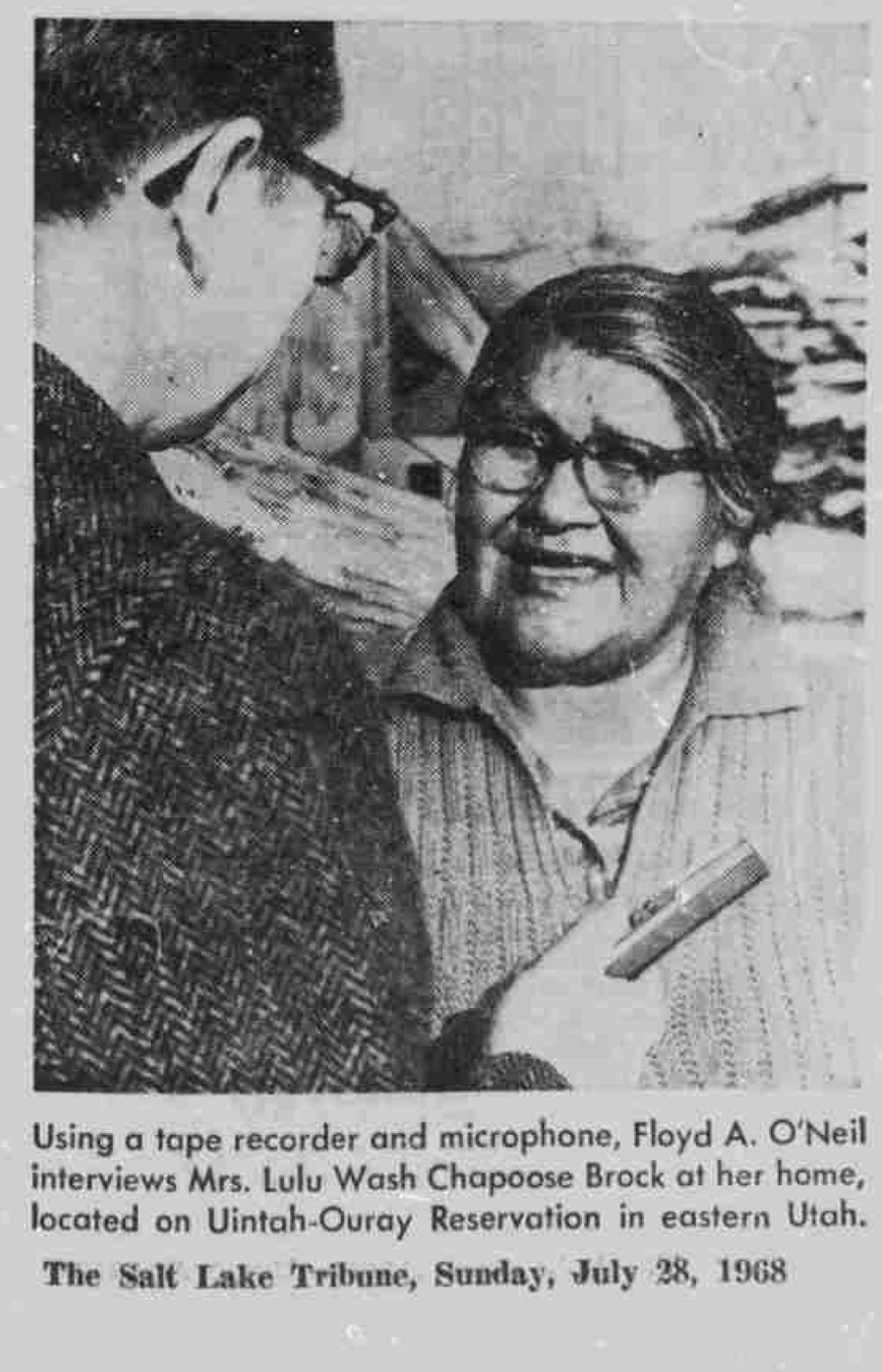

Eberly was a non-Native who worked in education. During their 1967 conversation, interviewer Floyd O’Neil asked her: “Back to this idea of what we can do for them [young Utes] for education. Is the local high school doing the job?”

She answered: “I don't think so. … This isn't only a problem here in the Uinta Basin. I think it's nationwide. Where Indian history, you know, per se, like we expect these kids to go to school and read about how the Mormons came to Utah and you know, conquered the valley and were great and brave and true and beat off the Indians here, and succeeded, you know, I just can't see Indian kids being overly sympathetic to that idea.

“Most of them hate history and I don't blame them.”

She also thought there should be more efforts to integrate the Ute language into education, suggesting “conversational youth corps” in high school “for two reasons: Number one, one of the complaints is that the kids speak Ute in class to get back at the teachers and if the teachers have a working knowledge of the language it wouldn't do any good to speak Ute, and I expect that would clear up the problem.

“And the second thing is whether the money, whether we get it or not, it's a bilingual situation and you're helping relations all around.”

Some students spoke Ute at home and knew enough English to get by, she said, “but any word that is the slightest bit unusual that comes up, they don't know what it is. Most of the time, they won't tell you they don't know; they'll just pass right over it.”

At one point, she said, “a few of teachers got together and they decided the next kid who spoke up in Ute in class and got caught, he was going to get nailed against the wall. That's his words”.

A Ute teenager she knew “was the kid that did it. He spoke in Ute, and I guess they nailed him against the wall, whatever that means. He told me, he told me what he did, behaviorwise, but he didn't do anything, either, just sat there and vegetated for the rest of the year. He probably will again next year. So here's a kid getting penalized for speaking his own language.

“And besides not learning any Ute Indian history. Also, you know, what he speaks, [there] is something bad about that, too. The whole thing is so negative. I don't know how they expect — I don't know how these kids have learned as much as they have.”

For more information about Doris Duke project interviews with Ute members, you can search descriptions here.

How to find Ute oral histories

The University of Utah hosts the largest repository of oral histories from the Ute Indian Tri

be, in its portion of the national Doris Duke collection . The heiress and philanthropist Doris Duke funded seven universities, including the U., to record first-person narratives from Native people across the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. Key to the U.’s effort was Floyd O’Neil of the U.’s American West Center.

Printed transcripts of the interviews are stored in the Special Collections of the U.’s J. Willard Marriott Library and available upon request. And librarians are currently working to digitize the collection , thanks to a recent grant from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation.

Special Collections also has the Ute Indian Oral History Project collection, which includes transcripts of tapes of interviews with 18 members from 1982 to 1985. The interviews included questions about their values, religious and family traditions, education and other topics.

Some interviews with Utes from Utah are included in other oral history collections at the U., and some are available online. For the Everett L. Cooley oral history project, for example, the late Ute spiritual leader and retired Episcoplal Rev. Quentin France Kolb in 1997 shared chilling memories of discipline at the Uintah Boarding School.

And researcher Kim Gruenwald included transcripts from several interviews in the draft for her thesis project on Ute education for Utah State University in 1989 . Those include conversations with Forrest Cuch, Gloria Thompson and Bob Chapoose. Cuch’s mother went to the Whiterocks boarding school, and he later experienced discrimination in the public schools; Thompson experienced the same. Chapoose attended the Whiterocks school.