Kyri Ungatavinekent-Duncan

Special to The Tribune

At a young age, I was always near my grandfather, Clifford Duncan.

He was a self-taught learner, cultural participant in ceremonies and celebrations, and an anthropology consultant.

Through his work and life experiences, Clifford was able to gain knowledge and understanding around working with those who identify differently than him. One thing he always expressed to me and my siblings is that we needed to graduate from high school.

“If you can hold education in one hand, and your culture in the other, you’ll go far in life,” he would say.

Education in his terms can be summarized and interpreted as navigating the world outside of being American Indian. With my family’s strong sense of cultural values and practices, the only thing left was to gain the tools of modern society.

In my mind, all I needed was to graduate from high school to succeed in my family’s eyes. I was a C-average student and had to make up a couple of classes that I failed during my freshman and sophomore years. It wasn’t until my U.S. history and German language teacher Hobart Willis gave me a strong push for me to pursue higher academia that I did.

“I see strong potential for this young man to go to college,” were the words that echoed through my ears when he spoke to my mother.

This sparked motivation to shape up my academic slump. I worked closely with the embedded Johnson-O’Malley advisers — Johnson-O’Malley is a federal act aimed at serving tribal education needs — to get concurrently enrolled with Utah State University’s extension campus. As graduation approached, I was slowly making strides to start my college career.

Looking to be a first-generation college student, there were many things I didn’t know. It was almost a miracle how Martha Macomber, the educational liaison between the University of Utah and the Ute Indian Tribe, came to my aid.

She provided key insights with applying to college, the FASFA financial aid form, scholarships, and other items around admissions. I applied to three colleges with the University of Utah at the top of the list.

Shortly after applying, I was denied admission.

Feeling defeated, I relied on my cultural teachings that my family has instilled. During this time, my father gave me strength with the words, “If you really want this opportunity, offer a word of prayer. That’s what we do when we face barriers.”

After following his guidance, I was informed with the wonderful news that the Beacon Scholars Program was going to sponsor my admittance to the U.

With adrenaline and not knowing what would be ahead, I made the 2.5-hour drive to Salt Lake City.

I was very fortunate that Beacon Scholars, known as First-Gen Scholars now, supported my admittance. Many American Indian students face isolation, imposter syndrome, culture shock and other mentally draining experiences when leaving home to attend college. Luckily, Beacon Scholars was a program that aimed to build a community and offer resources to first-generation students of diverse communities.

Through their mentorship-based structure, I made valuable relationships with peers, faculty, and staff who gave insights that can’t be conveyed through books or presentations. This also led to engagement with various student organizations across campus. With the collective support on and off campus, I graduated in 2020 from the University of Utah with a bachelor’s in strategic communications and a minor in multidisciplinary design — while making the dean’s list for multiple semesters.

Fast-forward to 2023, I currently hold the role as the advisor for the Inter-Tribal Student Association and engagement person for Native American folks with the Center for Equity and Student Belonging at the University of Utah.

As I navigated higher education with little information at hand, I can truly reflect and gain insight on what our American Indian students face at the U. Besides the bare necessities to attend the university (cost for attendance, housing, testing requirements, etc.), there are multiple factors that contribute to a fun, impactful, and successful academic experience. The most itching question is how can we break through the glass ceiling and start making that progress of fulfillment?

Speaking from my experience, I can break it down to two aspects that improve the quality of attending college for American Indians. The first is balancing previous and current environments. As stated in the beginning, I came from a family that believed in cultural teachings and communal support. Most students who I work with share the same upbringings. It was easy for me to get reconnected with those practices because I lived only two hours and some change away (luckily, I got my driver’s license by my freshman year of college). Other students, however, have to drive as much as 13 hours to get home. While some can drive, others have to book flights.

The second aspect is finding representation of your identity through community members, programming and shared spaces. To be quite honest, I was always in the middle of being with my Ute and white peers in high school. Regardless of that, I learned at a young age that my identity holds many aspects, such as my music taste, the way I dressed and communication style. Attending a predominately white institution, such as the U., I had to utilize these ways of seeing myself to find a sense of community and shared space.

American Indian students today face the same predicament. Although we have the American Indian Resource Center at the U., the enrollment number of those students is about 250 people. Being a large campus, the barrier almost seems impossible to overcome for those who are looking to reconnect with their community.

Both aspects could be summarized into building a sense of belonging for American Indian students. With the rise in college attendance from our Indigenous folks, there will be many revelations and resources that we should strive to preserve and implement.

One time, an American Indian youth approached me and asked, “Should I really go to college?” Filtering out the jargon and baggage I carried, I simply responded with, “College is one path that can lead you to what you want to do.”

Our American Indian people were born resilient and found any means necessary to survive. The creator put Ute/American Indians on this earth to be useful and utilize what’s in front of us. Whether you are a self-learner or take academic means to attain knowledge, we must still inspire our people to live the best life they can.

I would like to thank all those who support our American Indian students from K-12 to higher academia and The Salt Lake Tribune for giving me the platform to elevate the experiences stated above. Tah-gway-yahk (thank you).

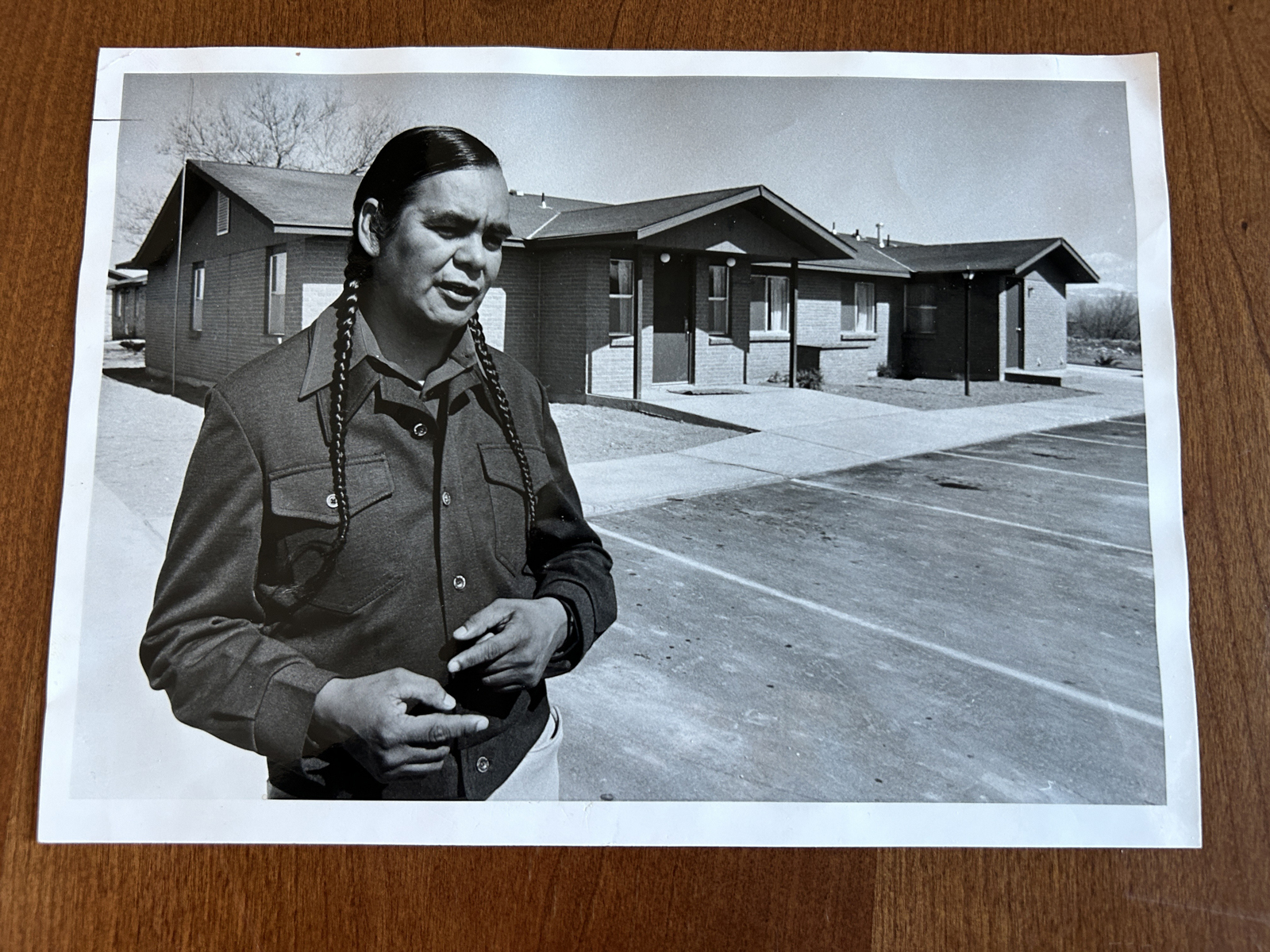

Kyri Ungatavinekent-Duncan, Uncompahgre of the Northern Ute Tribe, grew up on the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in eastern Utah. He is now the advisor for the Inter-Tribal Student Association and engagement person for Native American folks with the Center for Equity and Student Belonging at the University of Utah.