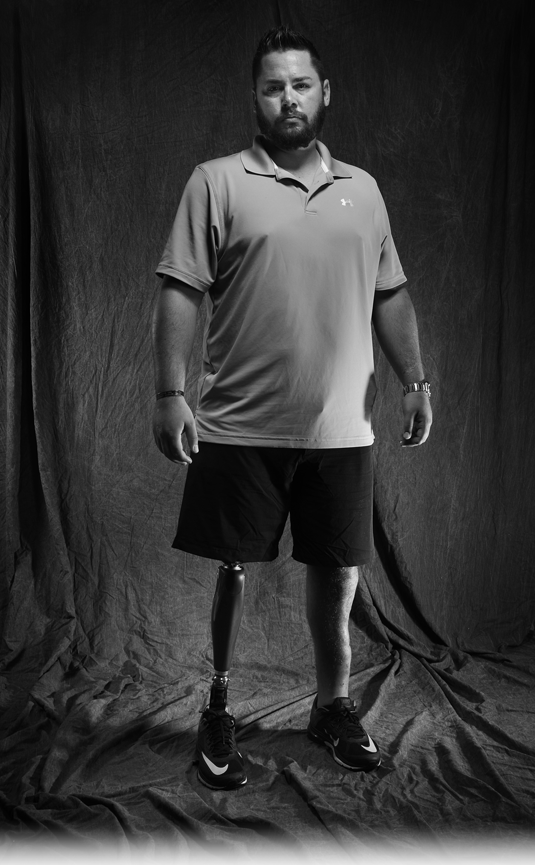

Bryant Jacobs' computerized knee joint, worth more than the Nissan Titan truck he recently financed, is among the most advanced pieces of medical technology in the world.

His carbon-fiber foot is the result of decades of research and development.

But the socket that connects all that technology to the stump of his amputated leg works about the same way as ones developed during the Civil War.

Back then, sockets were made of leather or wood; today, they're plastic or carbon fiber. Modern materials can be better fitted to the contours of a patient's residual limb, but the function remains the same for an above-the-knee amputee. The socket is intended to hold snugly around the limb, distributing the load of the user's weight across as much area as possible.

When the fit isn't quite right, or Jacobs wears it too long, he gets sores, abrasions and blisters.

Skin problems that develop under a socket frequently force amputees to take a break from using prosthetics. When that happens to Jacobs, he has to return to his wheelchair.

These challenges are why, just months after learning to walk in his prosthetic leg, the 34-year-old Army veteran is eyeing his next bionic step.