Sunlight streams through a wall of windows at the George E. Wahlen Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Salt Lake City as Bryant Jacobs takes a lap around the room.

He makes a turn around a set of treadmills and takes another lap inside the hospital's new $5 million physical-therapy center.

His physical therapist, Bart Gillespie, looks on.

"Time," Gillespie finally calls. "That's 6 minutes. Stop right there."

The walking path is 172 feet long. Jacobs has gone just shy of eight laps. At that rate, it would take him about 24 minutes to walk a mile. It doesn't seem likely he could do that, though; he's sweating and panting at the quarter-mile mark.

"That's not a bad start," Gillespie says.

"It sucks," Jacobs replies. "I'm getting cramps in my stump."

"But you're walking — you're moving pretty good," Gillespie says.

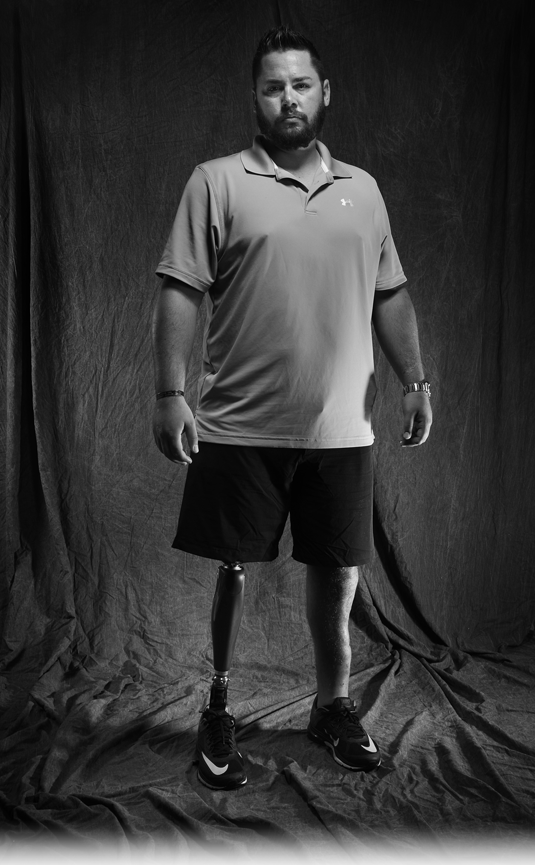

The way Gillespie sees it, Jacobs has made solid progress since his amputation, now nearly six months in the past. His gait is consistently improving; if Jacobs were to wear pants, rather than his usual shorts, few people would suspect he was missing a leg.

He's driving now, using his left foot as most drivers would use their right. The phantom pains he suffered in the months after the surgery used to keep him up all night; now they're rare. He's been able to cut his intake of painkillers in half — and has plans to go lower.

But Jacobs isn't satisfied.

"Everybody says it's a fast progression, but I don't really feel that way," he says. "Day to day, I'm getting sores on my leg. My socket still doesn't fit right — and that's distracting. I'm ready for the day when I can just put it on and be done with it."

It never really works that way. Residual limbs are swollen after amputations, so prosthetists know the first plaster cast they make for a socket is just the start. When amputees get into shape, as Jacobs is trying to do, the residual limb often shrinks. And in the hours between morning, when fluids have gathered in a limb overnight, to the afternoon, when everything is circulating better, a residual limb can lose an inch in circumference.

"It's a moving target on top of a moving target," says Jacobs' prosthetist, Lane Ferrin, who has employed suction, snowboard boot-style dial-down cables, and even Velcro to try to get Jacobs' socket to hold snug. "I know how frustrating that can be for some patients. But little by little they get more comfortable with it."