| OFFICER IN DISTRESS

| OFFICER IN DISTRESSThe hunt for an armed teen turns deadly. Certain that it's his fault, Detective Brent Jex will keep his shame a damaging secret for more than a decade.

The day after their terrifying talk, teacher Jana White found Justin Van Roekel in his first class. When she approached, he started tearing up again.

"I'm really worried about you," she told him. "I have people here to help you if you want it." Then White lied, saying she hadn't told anyone about their conversation, the crimes he confessed to and the violence he felt swirling inside himself.

She took him to the counseling center, where administrators explained an agreement to send him to drug treatment and said West Jordan police officers were there to talk to him. She couldn't stay. A bus full of students was waiting to go on a field trip to the University of Utah. When she got on board, White felt good, having set up a lifeline for a troubled student.

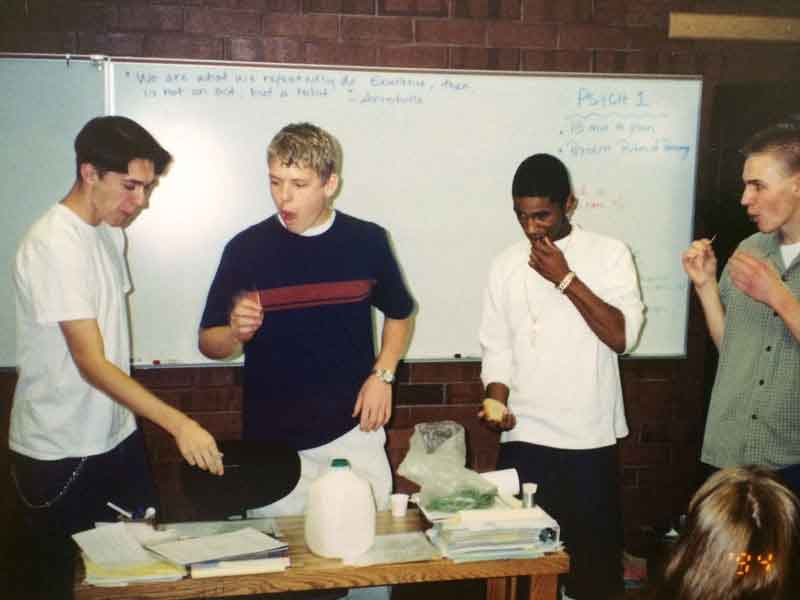

Justin Van Roekel, far left, participates in an activity in teacher Jana White's psychology class.

Photo courtesy of Jana White

Taking a seat in a small office, Detectives Richard Davis and Brent Jex introduced themselves and gave Justin a Coke. Jex asked, "So where do you want to start?"

"I got nothing to say to you," Justin said flatly, feeling he had been duped into a police interrogation. He said he was sorry he'd confided in White.

Davis asked him about the second McDonald's robbery. Justin smiled as he looked at his feet. "I don't know what you're talking about."

Davis asked if he was playing coy because he didn't want to cause trouble for Tyler Atwood. Justin said he and Tyler were ready to go to prison for what they'd done, but he wasn't going to rat on the only friend who understood him.

They got Justin to admit that his mom was alive, he didn't rob a bank, and he had never overdosed. Beyond that, nothing. Jex and Davis told Justin to call them if he changed his mind; then, they walked out of the office. They stayed at the school, waiting for Justin's father, who was on his way. Detective Richard Schaffnit, the school resource officer, slipped into the room to try to coax the teen to open up. The self-confidence Justin displayed with Jex and Davis had vanished. He got up and left the office in a hurry. Schaffnit followed, calling out to his colleagues to back him up.

"Here we go," Jex thought. The three cops trailed Justin into the parking lot, where Schaffnit caught up and put a hand on his shoulder to turn him around. Justin tensed and then crouched into a fighting stance, tears building.

Jex didn't hesitate. He forced Justin against a car, twisting an arm behind his back before slapping on handcuffs. He told Justin to calm down, said his father wanted to chat. The two of them could talk in private, Jex offered, thinking that might help. He didn't know how strained Justin's relationship with his father had become.

He had been thinking of Justin as an angry kid who robbed a few stores — troubled, but not dangerous. He started to worry Justin might do something desperate, and maybe violent, if things didn't turn around. But then the teen agreed to talk to his dad and seemed to be calm enough, so Jex removed the handcuffs.

The other detectives walked Justin back toward the school while Jex put away his cuffs. As soon as Justin made it inside the door, he ran. Davis and Schafnitt went after him, looking through a maze of lockers, while Jex, about 15 paces back, headed the only other way Justin could have gone, toward the gym. As he searched, Jex radioed for patrol officers to set up a perimeter around the school and to rush over to the Atwood home. They didn't find Justin or Tyler.

Justin Van Roekel likely darted into these banks of lockers to avoid police.

Photo by Scott Sommerdorf | The Salt Lake Tribune

Schaffnit went back to the counseling office, where Robert Van Roekel was waiting. He explained that Justin had run from officers and was a suspect in robberies. The father was stunned, then added that Justin hated cops, and his own opinion wasn't much better.

"Police are only good for documenting things like traffic accidents," Van Roekel said, according to police reports. "Cops only make things worse."

Jex and dozens of other officers would search for the fugitive pair all night, but first, Jex went back to the department to brief his lieutenant. On his way into police headquarters, Jex bumped into Officer Ron Wood, who was heading out on patrol.

"Hey, what's going on?" Wood asked.

"We're just trying to find some problem children," Jex said with an eye roll.

"Good luck with that."

Officer Ron Wood

Photo courtesy of the Wood family.

Wood was about 10 years older than Jex, having gotten into law enforcement as a second career, and yet he was one of the most athletic guys in the department. He had chiseled features, blue eyes and a mischievous smile. He kept his light brown hair buzzed short, with a small wave at the top of his forehead. Some in the department called him "Woody," others "Legs." He loved a good foot pursuit, and he was a mainstay on the department's softball team. He played basketball every Wednesday night with a group of cops.

Wood asked Jex whether he was going to make the next pickup game. Jex said he couldn't because he had a training class in Denver, starting Monday, but he promised to be there the next week. Wood said: "See you then."

Justin hid out with a friend named Colby on Saturday, then he met up with Tyler on Sunday. The two had a few beers and smoked some weed in Tyler's basement bedroom before falling asleep.

Robert Van Roekel, who had been searching for his son all weekend, pulled up around 7 a.m. on Monday, Nov. 18. Tyler's mom let him in. Van Roekel tried the locked knob on Tyler's door, then he knocked loudly. Inside, Justin sat on the bed, holding the Hi-Point pistol, saying nothing. Tyler responded for him: "You better get away from the door or you'll get hurt!"

Van Roekel backed off, but Tyler and Justin could hear him talking to Tyler's mom in the hallway. Tyler told Justin that he should just go with his dad, since it didn't sound like his dad would leave otherwise. Justin stood up, put the gun in the pocket of his blue windbreaker and opened the door.

Outside, his dad ordered Justin into the car, but the teen started walking down the road. Van Roekel followed, continuing to talk. When he got close, Justin turned and pointed the gun at his father's face.

Later, Van Roekel couldn't recall whether his son said anything. In that moment, all he saw was the barrel of the Hi-Point and Justin's fury. A second later, Justin started running. Van Roekel called 911 from his cellphone as he followed him.

"I've got a young man who has got a gun, and he is threatening me with it," he said between big breaths. "He is running right now." The male dispatcher verified the address and a few details before asking, "Do you know who it is?"

"Yes, it is my son," he yelled. "His name is Justin Van Roekel, and he has a gun and he pointed it at me. I'm following on foot, but he is running faster than me."

The dispatcher told him to stop following and then launched into a maddening series of questions about Justin's height and age, how his name is spelled, the color of his hair and what he was wearing. Justin had on white New Balance sneakers and blue jeans, a black T-shirt with the logo of the band Korn and a lightweight blue jacket.

Then a female dispatcher, who had been talking with patrol officers, jumped on the line. "Sir, do you know where this guy lives?" she asked. Van Roekel thought she meant Tyler, leading to confusion over who had the gun, who was his son and where exactly the armed teen was.

"Sir, do you think he is at Tyler's house right now?"

Van Roekel's voice was awash in anger as he responded. "No, he just left Tyler's. That is what I am telling you. I was there. I was with them. They were in their room, both of them. He came out. He was acting like he was going to come home with me. He walked out the door. He started walking down the road, and I said, ‘Come home.' Then, he turned around and pointed a gun at me."

Just as he finished this last sentence, Ron Wood pulled up in his police car.

As a traffic cop, Wood had no reason to be there. This was a patrol officer's job, but Wood was close and thought he could help. Van Roekel pointed the officer in the direction his son ran, and he ended his call with dispatch.

Wood parked in a short alley leading into Jordan Meadows Park, the same park Tyler had run into in September, when he was being chased by police. Ahead of Wood was a fence with an opening big enough for two people to walk through side by side and reach a pavilion and playground. On the right was a house, its backyard shielded by a 6-foot chain-link fence made opaque with brown plastic slats.

Wood, who never lost a foot chase, dashed through the opening. He made it two steps before Justin pulled the trigger.

Crouched against the fence, not 10 feet from Wood, Justin held the Hi-Point in his left hand, turned sideways. After the first bullet missed, Wood barely had time to turn toward Justin and start to drop into a crouch before the teen squeezed off two more shots. One round hit Wood near the center of his scalp, briefly grazing his head before passing through his skull and into his brain. The impact knocked him flat on his back.

IN THIS VIDEO: Listen to Robert Van Roekel's 911 calls.

Justin darted past his father, who had been trailing Wood, and took off into side streets. He put the gun back into his jacket pocket and searched for a way to escape. Just then, a white minivan turned in front of him.

Judy Linford, a grandmother of eight with white curly hair, was heading home from her water aerobics class when she saw Justin, the hood of his jacket obscuring his face and his hands in his pockets. He was blocking the street.

"What is this dumb kid doing?" she wondered as she swerved to get around him. Justin walked back into her path. She swerved again. Justin blocked her. Linford stopped the car, and the teen approached.

"I need you to take me for a ride," Justin said, clearly upset. "Please take me. Please take me."

Linford, in an upbeat, apologetic tone, said, "Oh, I can't do that." Just as she started to push the gas pedal, Justin pulled his gun and said, "Don't do that."

She stopped and unlocked the doors. Justin walked around front, got into the passenger seat and told her to drive. They hadn't made it to the end of the block before Justin started crying, slowly at first and then more desperately. "I'm already looking at 30 years in prison for what I've done, and now I've shot a cop. I shot a cop!"

Despite his chilling confession, Linford saw Justin as a troubled kid and felt pity, not fear. Still, she immediately started looking for a way to get him out of her car. He told her to turn right at a church. She responded by saying her husband was waiting for her, and she suggested she could drop him off. "No, go to the light."

Justin asked whether she had a cellphone. She handed hers over. With the gun resting in his lap, he called Tarek, his only close friend who owned a car. Tarek was at West Jordan High when he got the call. Justin, half-crying, half-screaming, said he was running from his dad, had shot a cop and had carjacked a woman. He wanted Tarek to meet him somewhere. Tarek could barely understand him. Justin said he really needed someone to talk to. Tarek told him to get out of the car, but Justin stayed.

Focused on her predicament, Linford didn't hear much of their conversation. Following Justin's orders, she had turned on 7000 South, which had two eastbound lanes. Between the early-morning commuters and the police rushing to help Wood, traffic wasn't moving more than 10 mph. Then, it came to a dead stop. She quietly unlatched her seat belt, and when she saw a cop driving slowly down the median, she thought, "This is it."

She swerved the van toward the officer, opened the door and put her left foot on the road as she waved her arm up and down to draw his attention. The officer drove right past her as Justin screamed: "Don't do it. Don't do it." Then he dashed out of the van, just as Judy jumped back in to stop it from continuing to roll forward.

"I'm either really dumb or really blessed," she'd say later. "I don't know which."

IN THIS VIDEO: KUTV interviews Judy Linford about her run-in with Justin Van Roekel.

Justin ran into the next lane, toward a purple Ford Explorer driven by Casey Hopes, a University of Utah student on his way to drop off an assignment. He tapped the gun on Hopes' window and then ran around the vehicle. The doors were unlocked, but Justin didn't immediately try the handle. That gave Hopes enough time to hit the gas, but with the traffic so clogged, all he could do was move up one car length. It was enough to spook Justin, who ran.

Detective Jim Lang had just unlocked his office at West Jordan Middle School when he heard on the radio that a teen had pulled a gun on his own father. Then, an unfamiliar voice screamed that Officer Wood had been shot.

Lang, who wasn't in uniform, threw on a bulletproof vest with "POLICE" written in big white letters across the chest. He ran toward his unmarked car, hoping to make it to Wood, one of his closest friends. But Lang didn't know where he was headed, and two officers he encountered as he drove were no help. He decided to go back to the middle school in case the shooter was heading that way, so Lang turned onto 7000 South and sat in the same traffic that blocked Justin's escape. Frustrated, he had pulled off to take side streets when he heard on the radio that a person matching the shooter's description had briefly carjacked a woman and was now on foot.

Lang stopped his gold Chevy sedan in the middle of the road, close to Reaper Circle, and watched as a teen, who he thought could be the shooter, walked toward him and then tried to wave him down. Lang opened the door and grabbed the radio to call for backup. When he stood up, Justin could see Lang's vest and realized he was staring at a cop. The detective saw the panic in the kid's face as Justin struggled to pull a gun out of his jacket.

Lang drew his .40-caliber Glock and fired two, maybe three, shots before Justin was prepared to return fire. He missed, and the teenager didn't seem to flinch. Instead, Justin placed the barrel of his Hi-Point against the roof of his mouth. He pulled the trigger and collapsed on the grass parking strip in front of a home. It had been 15 minutes since Van Roekel called police.

experiencing suicidal thoughts at 1-800-273-TALK (8255)

IN THIS GALLERY: Crime scene photos from the park where Justin Van Roekel shot Ron Wood.

About a half-block away, Mike Searle heard three gunshots from his driveway. The tow truck driver walked toward the park, saw an officer lying on the grass and rushed over.

As he approached, he swears he heard a faint, "Help me." Van Roekel, who had called 911 again, told dispatch he heard the same thing.

Searle had a contract with the city and knew just about every officer. He knelt to check Wood's pulse, then he grabbed the radio attached to his shoulder at 7:46 a.m. "Officer Wood has been shot."

Patrol Officer Denise Vincent was about a block away when she heard Searle's message. She was one of the officers dispatched to Van Roekel's original 911 call. Wood simply beat her to the scene.

She spotted Searle as she pulled up and asked him to watch her back as she began CPR. The shooter could return, she thought, and she wanted to keep Van Roekel, whom she didn't know, at a distance.

Van Roekel's updates to dispatch started to become unintelligible as shock set in. Searle grabbed the phone to demand that the ambulance hurry, then she gave it back as Van Roekel again answered questions about Justin. "It's my son, but I don't know him. He is not acting like my son." He mumbled something about Justin's drug use. "I don't know why he thinks he's so desperate."

Sgt. Bradley Sundquist and Capt. Gary Cox arrived and helped Vincent. Sundquist applied pressure to the head wound. Cox elevated Wood's feet and fixated on the blood that flowed from Wood's head each time Vincent pushed on his chest. Paramedics, delayed when firefighters got lost, weren't allowed to approach until police could verify that the park was safe. The all-clear came two minutes after Justin shot himself less than a mile away. It took another 20 minutes for a medical helicopter carrying Wood to take off for the trauma hospital at the University of Utah.

Van Roekel agreed to go to the station with Officer Dan Briggs, but first he wanted to make sure his car was locked at the Atwood home. It is unclear whether police told him at the park or later at the station that his son had killed himself. But during that brief detour, Van Roekel told Tyler's mom that Justin had shot a cop. Tyler, who overheard the conversation, gathered a few of his things and slipped away.

Police worried Tyler might also be violent, so Schaffnit put the high school on lockdown for two hours. The school erupted into chaos, with TV trucks, police officers and scared parents.

Classmate William West also had heard Justin say he wanted "to kill someone, his dad or a cop. … It's just that no one took him seriously."

Officers found Tyler wandering the neighborhood at 5 p.m. and arrested him without a fuss.

Brent Jex and a group of detectives were packed into a hotel conference room, ready to learn interrogation techniques, when a woman slipped a pink note in front of him. It urged him to call the Salt Lake Metro Gang Unit. He reached Sgt. Bill Robertson, who delivered the news: Ron Wood had been shot, his prognosis wasn't good and a West Jordan officer had taken down the suspect.

Jex, his mouth agape, tried to process as Robertson continued: The shooter was Tyler Atwood. As soon as he hung up, the phone rang again. Robertson had a correction. The shooter was Justin Van Roekel.

"Just instantly, I couldn't even respond," Jex said.

He stood in the hallway, staring blankly, his mind running over the last time he saw Wood, not long after he released Justin from his handcuffs and watched as the teen fled. If only he had kept Justin in custody.

He waved his Utah colleague Luis Argueta out of the class. "We have to go back." As they drove, Jex got a call from Scott McKane, a veteran reporter for Salt Lake City's Fox affiliate, who said doctors had pronounced Wood dead.

On a two-hour stretch of road with no cellphone service, Jex continued to replay Friday's events at the high school.

"You want to talk about straight-up regret," he said. "And there was nothing anybody could have said to convince me otherwise. I was angry. I was angry at myself. I was angry at a lot of people. I was angry at other officers."

Jex drove straight to the station. Everyone else had already begun grieving, and he was trying to catch up. He walked near the interview room where Tyler sat alone. Detectives were milling outside, including Richard Davis, who had worked the robbery cases with him. Jex caught his eye and quietly asked, "What the hell? What happened here? How did this go so wrong?"

Jex had already come to one painful conclusion: Ron Wood's death was his fault, and he knew his fellow officers blamed him, even if they wouldn't say as much to his face.

At 2 a.m., the squad room was still packed with officers and one civilian, Mike Searle, the tow truck driver who first reached Wood. They were telling stories about "Woody." Jex was there, but he didn't say much.

One officer told of the time Wood confronted a man riding a motorcycle on a private field. When the motorcyclist tried to speed off, Wood ran after him, caught up and pulled the guy right off the bike. Then, there was the time Wood chased a man who was wandering the city naked and, eventually, hit him with some pepper spray. They talked about how he always carried a bag of new socks in his trunk to hand to homeless people, how skilled he was on a motorcycle and how no one, and they meant no one, was more prolific in writing tickets.

The department's computer system tallied citations each officer gave in a year, up to 999, since no traffic officer got close to topping 1,000. But in 2001, Wood wrote 2,697 tickets. His personnel file included no complaints. Instead, he received a couple of letters thanking him for his professionalism.

Jex thought the gathering and the occasional laughter were cathartic. A few days later, he would have a far more negative reaction to the department-organized "critical incident stress debriefing."

Officers and support staff were urged to pick a session, where they would sit in a semicircle while a therapist with long white hair and a beard, glasses perched on his nose, stood before them. Officer Denise Vincent bolted when the first cop began talking. When Jex walked into his session and saw the therapist, he thought, "Nice try."

"If that meeting lasted 15 minutes, I'd be surprised," he said.

The therapist asked each officer to state his or her name and involvement in the case. "Screw you, I don't want to be here," one blurted.

As the others spoke, Jex's anger grew, his arms crossed as he stared at his shoes. When it was his turn, he just said: "It doesn't matter what I did."

Jex had no intention of ever discussing this case — not with a department-issued shrink, and not with his co-workers. Not even with his wife. And, for years, he didn't.

Ron Wood last visited his family Nov. 17, when he came, as always, to Sunday dinner. He insisted on giving his father, Blair, a stereo originally intended as a Christmas present. When he left, he gave his mom, Birgitta, a big hug.

The next morning, the Woods sat transfixed by TV coverage of a police officer who had been shot in West Jordan. Birgitta's sister called. "Is Ron OK?" Birgitta wasn't sure, but she didn't have any sort of ominous feeling, and she was pretty sure she would if her son were hurt. The phone rang again. This time, it was West Jordan Police Chief Kenneth McGuire. Even hearing that Wood had been shot didn't send Birgitta into a panic. She assumed it was in his arm or leg. He'd be all right. She rather calmly called her four other children before heading to the hospital.

They arrived at the medical center the police chief directed them to, only to find out their son wasn't there. He had been taken by a helicopter to the University of Utah's hospital. That's when Birgitta started to worry.

Officer Ron Wood with his mother, Birgitta.

Photo courtesy of the Wood family

Wood's wife, Lourie, had been watching the news in her pajamas, but she hadn't heard anything about a shooting and wouldn't until she got a knock on the door.

Wood met Lourie Pulido on a dating site, when the Filipina was working in the United Arab Emirates. She was slight, soft-spoken and a little sarcastic. She knew English but wasn't confident in the language. Lourie loved how family-oriented Ron was, and when he finally flew out to meet her in person, she had assembled her whole family to greet him at the Manila airport. Lourie moved to Utah about a year and a half after they started talking, and she married Ron in May 2001.

Somehow, Lourie didn't learn that Ron was a police officer until after she landed in Utah. Her uncle was a police captain in the Philippines, and while she respects cops, she viewed law enforcement as a dangerous profession.

Officer Ron Wood with his wife, Lourie.

Photo courtesy of the Wood family

"It scared me all to heck," she said. She pushed Ron to find another line of work, and he had started taking computer programming classes, following the career path of his younger brother, Marlan. They were also trying to have kids and were still grieving after Lourie's miscarriage a few weeks earlier.

On the morning of Nov. 18, the couple fell into their normal routine. Wood left the house at 5:45 a.m., telling Lourie, "I love you. Take care." She was flipping channels when there was a knock on the door. It was the police chief.

"Something bad has happened," McGuire said, not elaborating. He encouraged her to get dressed, and as she did, she thought, "Ron must really be hurt for the police chief to show up personally."

They rushed to University Hospital, where most of Wood's family members were already waiting.

He was in the neurocritical care unit, his head heavily bandaged and his hands in bags, a precaution to protect gunpowder residue in case he had fired his weapon. The metallic smell of blood overwhelmed the room. The family held vigil as Wood suffered a series of heart attacks. Doctors informed them that he had very little brain activity.

Marlan Wood had grown increasingly close to his big brother in recent years. The two had gone paintballing just a few days earlier, and as the family sat quietly, Marlan stared at the tiny welts on his brother's muscular torso.

Birgitta, who was rubbing her son's feet, recalled an article she read in the Ensign, a Mormon magazine, that described a mother instructing her dying child to "go where the light is." Birgitta began saying the same thing to her son, preparing herself to let go.

Lourie couldn't fathom saying goodbye to her husband of only a year and a half. "I was like, ‘No. No, he's not going to go. He's going to stay.'" At that moment, she felt betrayed. "He promised that we were going to stay together forever."

A doctor pronounced Ron Wood dead at 10:30 a.m. He was 39 years old.

IN THIS GALLERY: Photos from Officer Ron Wood's funeral.

So many people showed up for Wood's service at Copper Hills High School that officials had to shuttle hundreds into the gym, where they watched the proceedings via closed-circuit television.

Marlan thanked the community. "We have seen messages posted on the internet and in front of businesses. I know some of you may have traveled great distances, and we thank you all for being here. We also, as a family, would like to express our condolences to the family of the boy who took Ron's life as well as his own. There were two families that lost a son that day, and we feel sorry for their loss as well."

Blair Wood, Ron's father, had asked Marlan to mention the Van Roekels. Most of the Wood family had already forgiven Justin, a feat made easier by the teen's suicide.

"There's no point in hating anyone," Blair told reporters at the time. "It would only ruin more lives. Ron wouldn't want that, and we don't want that for our family."

Justin had no funeral, at least not in Utah. His ashes were sent to relatives in New Mexico, where their disposition is unknown.

A 3-mile procession accompanied Wood to the city cemetery. Three helicopters flew over the gravesite, and the one that had carried him to the University of Utah diverted to the hospital in a symbolic salute.

Over the radios, a dispatcher began the traditional end of watch. It began with a request for response from Motor 72, Wood's call number. His family, surrounded by hundreds of police officers at his graveside, waited silently. The dispatcher spoke again, pronouncing Wood's tour of duty complete: "You have served company and West Jordan with great honor and integrity. May God go with you."

Bagpipes played in the distance.

IN THIS VIDEO: Brent Jex describes the first time he saw Lourie Wood after the death of her husband.

Jex's guilt was so raw that hugging Lourie Wood at the funeral caused him physical pain. He barely held it together when Wood's casket passed him at the graveside service, and he lost it when the dispatcher called out the end of watch for Motor 72.

Unlike Wood's family, Jex felt no forgiveness. In his eyes, Justin was a murderer, and Tyler was just as much to blame.

On the day of the shooting, five officers had executed a search warrant at the Atwood home. They found a bank bag under Tyler's dresser that had checks made out to McDonald's and receipts dated Oct. 25, the day of the second robbery. The officers also found a black backpack that held cigarettes, matching those taken from the Food 4 Less. They didn't find the "Scream" masks, but they had enough. A search of Justin's room came up with nothing helpful.

The blood samples from the stolen blue Civic and the tissue found in the parking lot conclusively linked Tyler to the McDonald's robbery. He was going to prison, and likely for a long time, even though he was a teenager and not directly involved in Wood's shooting.

Jex pressed prosecutors to craft a conviction that would leave Tyler in a cell until every officer on duty the day Wood died became eligible to retire — at least 20 years. The detective thought, "I don't want to have to deal with him again."

But even that wasn't enough. Jex needed redemption for letting down his friend, his department, his profession. He just didn't know how to go about it.

A few days after the funeral, Michael Minichino, an agent with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, paid Jex a visit, saying, "I know where the gun came from."

He told Jex about a rural store that had 15 handguns taken in a smash-and-grab. One of them was the Hi-Point. Minichino asked Jex to help him figure out how the gun ended up in Justin's hands.

"And that's all I needed to hear," Jex said.

Tracking the gun gave him a place to direct his anger. He could seek not only redemption but retribution, not just against Tyler but anyone who had ever held the Hi-Point.

"That's all I could think about, all I wanted to work," he said. "I was target locked."

Mental health resources

Learn about the Utah Fraternal Order of Police Mental Health Program.

See DunamisPolice.org's page about trauma and mental health.

Find help for anyone experiencing suicidal thoughts at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). Utah also has crisis lines statewide.

The SafeUT app offers immediate crisis intervention services for youths and a confidential tip program.