| OFFICER IN DISTRESS

| OFFICER IN DISTRESSSeeking redemption, Detective Brent Jex hunts for everyone who ever touched the stolen gun used to kill Officer Ron Wood.

Broke, drunk and itching to get high, Andrew Valdez, Anthony Montes and two buddies crept toward the Western Farm & Home Supply in Utah's Uinta Basin, an area dotted with oil fields near a Ute Indian reservation. Late at night, with no one around, Montes threw a rock through the glass door.

Western Farm was a catchall where locals could get their lawn mowers fixed or rent DVDs, but this crew was after only the firearms. Shattering display cases, the four made off with 15 handguns, each with a price tag attached by a string. They took only the weapons off the top shelves, ignoring the ones in other cases and the dozens of rifles leaning against the wall.

Why the hasty retreat? Most likely, they thought they had tripped an alarm. They hadn't. By walking through the busted glass door, they avoided the motion detector attached to the frame. Even if it had gone off, it would have made an annoying noise audible only to the burglars in this sparsely developed commercial area. The alarm didn't call police. And the store's security camera wasn't working.

The assistant manager arrived to open the store at 7:30 a.m. on Dec. 11, 2001. He saw the shattered glass, footprints in the snow and, most important, a smattering of blood drops near the gun cases. One of the culprits must have gotten hurt, but it wasn't clear how.

IN THIS GALLERY: Andrew Valdez, Anthony Montes and two others broke into Western Farm in 2001. See the crime scene photos.

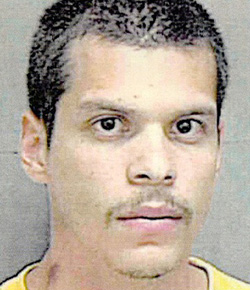

Andrew

Valdez

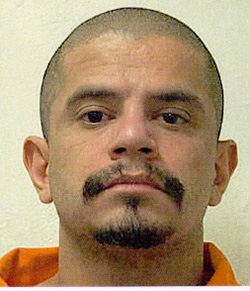

Anthony

Montes

By the time the assistant manager called police, the burglars were back in Salt Lake City, after driving 2½ hours in a red Geo Metro with the guns wrapped in towels and hidden in the trunk. Valdez, 24, was a member of Surenos Chiques, one of the state's larger Latino gangs. Montes was 38, a three-time felon. Both had criminal pasts involving burglaries and drugs.

They checked into a Super 8 motel at 5 a.m. and used the room phone to call friends and fellow gang members, trying to find someone to take the whole haul for $3,500. The burglars' plan was to split the cash and use it to buy drugs and maybe a few Christmas presents.

They had mostly Smith & Wesson .40 calibers and Ruger 9 mms, though they also had two revolvers and a Hi-Point C9. That last gun, molded in an Ohio plant nine months earlier, was selling for $79.26, by far the cheapest of the lot.

Carlos “Psycho” Trujillo

One of the potential buyers they called was Carlos Moses Trujillo, who went by the street name "Psycho." He is Valdez's younger half brother, and he also was a member of Surenos Chiques, though he had connections to other gangs. Psycho reached out to "Droopy," a guy saddled with his street name because of his sad, downturned eyes and a perpetual frown reminiscent of the cartoon dog. Droopy was a member of the King Mafia Disciples and, at 27, had worked his way up to being a "minister," essentially a shot caller. Unbeknownst to Psycho, Droopy also was a confidential informant for the FBI and the Metro Gang Unit.

Four months earlier, another KMD member went to the wrong house party, got in a fight with rival gang members and stabbed a 24-year-old man to death. Seeking help that night, he called Droopy, who picked him up and hid him. The FBI found out about Droopy's involvement and gave him an ultimatum: He could reveal the killer's whereabouts and become an informant, or he could face charges as an accomplice to murder.

The feds caught Droopy at a vulnerable time. He had young children, and he'd been trying — and failing — to distance himself from the KMD. "At that point, it was a means to an end," Droopy said. In FBI jargon, he became a "cooperating witness."

The feds, along with the gang unit, saw the KMD as a potential test case in Utah, where they'd try to dismantle the whole gang using racketeering charges. Agents Scott Suitts and Juan Becerra gave Droopy a small rectangular recording device that he could slip into his pocket, no wires needed. He turned out to be a well-placed informant, even on a few things that had little to do with the KMD.

After getting the call from Psycho, Droopy contacted his FBI handlers and told them about the cache of stolen guns. He offered to set up the buy if the agents could get the cash. He didn't hear back for a full day, and in that time, the burglars moved to a Ramada across the street. They had already sold 11 of the guns. Droopy told Psycho he'd take the rest.

"When you are dealing with stuff like that, there's a window of opportunity," Droopy said. "You either get it or you don't."

“

When you are dealing with stuff like that, there's a window of opportunity. You either get it or you don't."

"Droopy," an FBI informant

He picked up Psycho and drove to a Salt Lake City motel, knocking on Room 162. A shirtless man with "Mendez" tattooed across his lower back answered the door. When Droopy flashed the cash, Mendez pulled out three of the four remaining guns. Droopy said he wanted the fourth as well, but Mendez said that one wasn't for sale.

FBI agents watched as Psycho and Droopy left the motel. They didn't attempt to arrest anyone, wanting to protect Droopy's cover. Instead, they wrote a report on the gun buy and shelved it.

About six months later, the FBI brought racketeering charges against 10 KMD members, securing lengthy prison sentences for many of the gang's leaders. Droopy has since moved on from gang life and keeps a low profile. He says just about every one of the guys he knew in the gang is either in prison or dead.

Michael Minichino, a special agent with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, made it to Western Farm the day after the heist.

Minichino had been an ATF agent for a year when he was assigned this case, but it felt as if he'd been in the bureau his whole life. His father, John, had joined when the ATF was still a division of the IRS. Minichino's family moved all over the country, including two stints in Utah, where his father eventually became the resident agent in charge of the Salt Lake City office before retiring in 1997.

Tall and broad-shouldered with dark black hair, Minichino has a ready smile and arched eyebrows, which give him a mischievous appearance. The Western Farm burglary was his first serious gun case and he didn't have much to work with. He started by searching for a disgruntled employee but found none. No witnesses came forward. The blood didn't match anyone in the system. The best news Minichino received came from Salt Lake City police. Officers there got one of the Western Farm guns from a mother who found a pair of firearms in her teenager's room. A third gun surfaced during an investigation of a drive-by shooting in which no one was hurt.

ATF Special Agent Michael Minichino while qualifying at a gun range east of Salt Lake City.

Photo by Scott Sommerdorf | The Salt Lake Tribune

Suitts and a buddy on the gang unit gave Minichino tidbits about Droopy's gun buys, but, worried about jeopardizing the racketeering case, they wouldn't let him see their reports or talk to their confidential witness for months. All they gave him was a rough description of the men in the hotel room and the first name of the go-between, Carlos. "By the summer of 2002, there wasn't much for me to do," Minichino recalled. "I was waiting for a good lead." He got one that August, when someone arrested for a minor crime offered information to avoid prosecution.

In a matter of days, Minichino sat across from the confidential source at the ATF's Salt Lake City office. As he listened and later checked out the story, he saw three options: The informant watched the crime go down, participated in it or got the rundown directly from one of the burglars. The information was that good.

The source said Anthony Montes smashed the door and was the first to enter Western Farm, followed by Andrew Valdez. They were joined by Lino Montes — Anthony's brother — and a friend named Steve Mendez. The Montes brothers supposedly started tossing the handguns to the other two, who would load them into a truck. Valdez missed one, and it hit him in the face, splitting his lip, which explained the blood drops found in the store.

The informant picked all four out of photo lineups and reported seeing the guns at the home of a guy named Carlos and at a Ramada Inn.

Finding a "Carlos" with ties to Valdez, Minichino put together one last photo lineup. The source pointed to Carlos Moses Trujillo, aka "Psycho."

An assistant U.S. attorney considered the source's statements solid enough to get a search warrant for Valdez's blood. What better way to nail this case than to match it to the DNA found at the crime scene? Now Minichino just had to find Valdez.

As Minichino searched for the Western Farm burglars, he got a call from West Jordan Detective Brent Jex about three teens — Tyler Atwood, Justin Van Roekel and Sean Tims — who were caught in September 2002, casing a neighborhood with guns, masks and a night vision scope. At Jex's request, Minichino tracked the seized guns. They didn't come from Western Farm.

One was tied to a dealer who didn't keep the appropriate records, and the other was sold at a Texas gun show. Minichino couldn't prove that either had been stolen, which would have gotten the teens locked up.

Two months later, the Hi-Point stolen from Western Farm was in the hands of Tyler and Justin, who used it in a few armed robberies. Then, on Nov. 18, 2002, Justin pulled the trigger four times, ending two lives — Officer Ron Wood's and his own.

Minichino's investigation into the Western Farm burglary immediately morphed into something far more personal: tracking a gun used to kill a fellow cop. He gained a partner in Jex, a detective driven by the anguish of losing a friend and by a hidden need for redemption.

IN THIS VIDEO: Detective Brent Jex explains what the gun investigation meant to him, as he holds a tape of the 911 calls from the day Officer Ron Wood was killed.

Prosecutors succeeded in moving Tyler's robbery case to adult court, though he was still a minor. That's the outcome Jex wanted, but it came with a downside. Tyler's defense attorneys refused to let Jex and Minichino talk to their client about the Hi-Point 9 mm. Without Tyler talking, Jex wondered whether this gun investigation would go anywhere.

"I thought that no one who was involved in selling a firearm that was used to kill a cop would be willing to cooperate," he said.

Also, Minichino had been taught that stolen guns rarely stayed in the same hands for long. After the Western Farm burglary, the Hi-Point had been on the streets for 11 months, and there was no telling which path it had taken on its way to Tyler and then Justin.

With Tyler off limits and Andrew Valdez and Anthony Montes still at large, the investigators were struggling for a starting point — then, a high school teacher called police.

Ten days after his friend killed a cop and then died by suicide, Sean Tims was struggling. Terry Jensen, a teacher at Valley High in South Jordan, could see it, so he approached Sean in the parking lot.

Sean said he expected to be arrested because of his ties to Justin and Tyler. Jensen joked that Sean must have been involved in an armed robbery. Taking the question seriously, Sean said he didn't do the crime, but he said he had some of the stolen cigarettes stashed under his bed.

The police raided his house that morning, Sean said, and he woke up to an officer pointing an AK-47 at his face. Jex later said that never happened. Sean was exaggerating. Jensen said he suspected as much at the time.

They talked again after class, and Sean remained agitated. Jensen told him that if he did nothing wrong, he had nothing to worry about. Sean blurted out that he'd sold Justin and Tyler the guns that police seized during their September arrest, and that he had been the getaway driver for at least one robbery. But, he said, Tyler was the only person who could implicate him and he was sure Tyler "would rather kill himself" than rat him out. He left Jensen's classroom. The teacher realized his student had just confessed to a crime. Jensen called Sandy police, who, in turn, contacted Jex.

Sean, who erroneously believed there was such a thing as "teacher-student confidentiality," refused to say anything to Jex, but his mother let police search his room, where officers found cigarettes and a throwing knife. Resigned to the idea that Sean wasn't deeply involved, Jex sent the teenager to juvenile detention, using his September arrest to file a charge of carrying a loaded firearm in a car.

Sean's case seemed like nothing more than a distraction until, in mid-January, his attorney wanted to cut a deal.

Minichino, Jex and another West Jordan detective went to the detention center, where Sean told them about the McDonald's and Food 4 Less robberies. He said he saw Tyler and Justin with the "Scream" masks and heard them brag about other crimes. He also said a "Mr. C" sold the Hi-Point to Tyler.

A search of the gang-unit database brought up Michael Sathaphan, a member of the Original Laotian Gangsters who went by Mr. C. He was 17, with a juvenile rap sheet that included stealing cars and evading arrest. Jex used car-registration records to find Sathaphan's address.

Michael

“Mr. C.” Sathaphan

In the early hours of Jan. 29, 2003, Jex stood by as the heavily armed West Valley City SWAT team stormed the two-story duplex and handcuffed Mr. C and three relatives. Jex and Minichino found 71 grams of meth on the floor of the big bedroom Sathaphan admitted was his. They found a Browning handgun in Sathaphan's closet and pulled two more firearms from under the bed. Inside a black day planner was $2,795 in cash, along with a list of what appeared to be people who owed money.

As the search continued, Jex sat next to the handcuffed Sathaphan and said the raid stemmed from the murder of Officer Ron Wood. Jex said he was pretty sure Sathaphan sold the Hi-Point to Justin or Tyler.

Sathaphan, who stood 5-foot-11 and was a muscular 180 pounds, seemed genuinely pained and was willing to talk, in part because he hoped his cooperation could get him a lighter sentence. During an interview, Sathaphan said he met Tyler a little more than six months earlier and bought cocaine from him. But soon, Tyler was coming to him to get high, buying coke at least 30 times, Sathaphan said. On one of those occasions, Sathaphan said, he sold Tyler the Hi-Point for $100. Sathaphan said he got the gun, and plenty of drugs, from a Surenos gang member who went by "Shorty." All he knew was that Shorty hung out with a guy who went by "Wicked." It was thin, but enough. Sathaphan's reward was a sentence of five years and three months.

Busting Shorty didn't take any early-morning SWAT raid. Instead, it required a deep dive into old police files.

The investigators discovered that Shorty was the street name for Francisco Marcos Echeverria, a 28-year-old Guatemalan national who had been granted asylum. The databases didn't show much in the way of a record, though Echeverria's wife, Kara, had been arrested more than once for dealing drugs.

Jex got creative. He searched dispatch logs, not arrest records, for Shorty and got a hit. It involved a case the district attorney decided not to pursue. Jex and Minichino pulled the file.

Francisco “Shorty” Echeverria

A little less than a month before Wood was killed, Salt Lake County sheriff's Detective Rudy Chacon had busted Kara Echeverria for having drugs and a gun in her car. Kara, who was on parole, admitted that the stuff was hers and then volunteered that her husband also carried guns and, likely, dope in his car. She even told police Francisco's silver Honda Civic was parked in the backyard of a nearby house.

Chacon found the car and spotted the tip of a handgun peeking out from under a jacket. The detective decided he had probable cause to search the unlocked car, finding a Glock, $6,888 in cash, 2 ounces of meth and nearly 4 ounces of cocaine. Chacon left a receipt in the car, letting the owner know deputies had been there and had taken the items. The district attorney thought the case was weak, with no direct tie between Francisco and the contraband, and declined to prosecute.

Minichino thought he could take the case federal. He got a search warrant for the Echeverrias' house and, on March 3, 2004, the gang unit sent a team. The officers knocked, and, to their surprise, Francisco answered. He showed none of the remorse exhibited by Mr. C. He denied knowing Sathaphan or Tyler, and he said he certainly didn't sell anyone a Hi-Point. He ended up pleading guilty to drug dealing and took a five-year prison sentence.

Where did Francisco get the Hi-Point? His refusal to talk left Jex and Minichino stuck. But they did have some success in tracking the Western Farm burglars during the previous months.

The gang unit had named Valdez and Montes joint public enemies No. 1, a move that led to plenty of media coverage and a stream of new tips.

One informant told detectives that Valdez was hiding in a beige duplex in Ogden. Late on April 25, 2003, an FBI agent said he spotted Valdez through a window. Ogden's SWAT team surrounded the house, backed up by six Metro Gang Unit detectives.

IN THIS VIDEO: ATF Agent Michael Minichino explains how the gun investigation affected him.

Minichino hesitated when he received the call and decided to pull "a reverse Murphy," he said. Based on Murphy's law, the adage that anything that can go wrong will go wrong, he believed the chances of bringing in Valdez and Anthony Montes were better if he stayed away.

Jex, who thought Minichino's reasoning was hilarious, had no intention of missing the arrest. He sat on the perimeter.

A woman and her son, arms up, were the first to exit the house, then came another woman. After detectives called for everyone to leave, out walked Valdez, followed by Montes.

His "reverse Murphy" having worked, Minichino rushed to get the first crack at interviewing the men he'd hunted for eight months. But when he got to the Salt Lake County Sheriff's Office, where the suspects were waiting in separate interview rooms, an FBI agent warned him that Valdez was already asking for a lawyer.

"When they invoke counsel, then they're off limits unless they initiate contact, so I just said, ‘My feelings aren't hurt. That's your stance right now, and the ATF office number is 524-7000.' I probably said it, like, three times," Minichino recalled. "I didn't think either one of them was paying attention."

Three days later, he received a call. A woman said she was reaching out on behalf of Montes. That led to a recorded confession that began: "I, Anthony Montes, was home on a snowy night."

Montes threw the rock through the door, he said, and Valdez was the one who cut himself. "We loaded up on guns," he said.

Minichino had Montes' taped confession, and he got a blood sample from Valdez, which matched the DNA found at Western Farm. Shortly before this raid, investigators found Carlos "Psycho" Trujillo at his mother's house. He admitted to brokering the gun sale, and each man would plead guilty.

Prosecutor Leisha Lee-Dixon, a favorite among the gang detectives, made sure no amount of cooperation would result in a lesser sentence for Valdez or Montes. In making her case, she pointed to Ron Wood's killing, arguing that the pair should shoulder some responsibility.

"Can we say, first of all, that Officer Wood would not have been killed?" she said in January 2004 at Valdez's sentencing hearing. "I think the fact that this defendant stole that particular firearm, put it in the stream of commerce, which eventually led to this individual who shot Officer Wood, certainly gives him some culpability."

Valdez's attorney argued that the burglary was a spur-of-the-moment decision with the goal of scoring money to buy drugs. Valdez told the judge: "I know I made a mistake, but I had no intention of nobody getting hurt. It was a one-time thing. ... It breaks my heart every time I think about the stuff that happened."

U.S. District Judge Dale Kimball gave Valdez a stiffer penalty than the law required — eight years and four months in federal prison. Later that year, he gave a similar "upward departure" to Montes, sentencing him to 13½ years.

Psycho, who had no priors, was charged with possession of a stolen firearm. He was sentenced to serve 18 months.

By the time they were done, Jex and Minichino had recovered 11 of the 15 stolen guns. They tracked the Hi-Point's path from Valdez and Montes to a man named Teddy Barrera, who knew Droopy, the FBI informant. The investigators also were sure that Tyler bought the Hi-Point from Sathaphan, who got it from Francisco Echeverria. But it appears that at least one suspect got away: as Minichino could find no connection between Barrera and Echeverria.

Isidore Theodore “Teddy” Barrera

Tyler Atwood

In the following years, the prosecution of the other three men — Barrera, Mendez and Lino Montes — unraveled, when prosecutors wouldn't divulge the identity of the first confidential source.

But Jex didn't track any of that. For him, the Hi-Point investigation ended in April 2004, during a lunchtime ceremony at the office of the U.S. attorney for Utah, where Sen. Orrin Hatch, R-Utah, and U.S. Deputy Attorney General James Comey, who would later become the FBI director, presented Minichino and Jex with a plaque and a certificate honoring their investigation.

It should have been a proud moment, but Jex wished he could have avoided the recognition. He couldn't stop thinking of Ron Wood and the opportunity he had to arrest Justin days before the shooting.

"Internally, I'm thinking, ‘So what?' I light a house on fire and then help put it out and everybody's like, ‘Oh, thanks for helping us put it out.'"

As the years passed, his guilt eased. He thrived within the Fraternal Order of Police, becoming president of the state lodge in 2012. The post gave him a new vantage point from which to view his profession and an avenue to get involved politically. Generally, he felt fulfilled and invested.

But then another friend in blue died.

And six months later, another.

Mental health resources

Learn about the Utah Fraternal Order of Police Mental Health Program.

See DunamisPolice.org's page about trauma and mental health.

Find help for anyone experiencing suicidal thoughts at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). Utah also has crisis lines statewide.

The SafeUT app offers immediate crisis intervention services for youths and a confidential tip program.