Author points to an alternative suspect

If not Joe Hill, who killed the Morrisons?

If labor troubadour Joe Hill didn't commit the murders for which he was executed on Nov. 19, 1915, then who did?

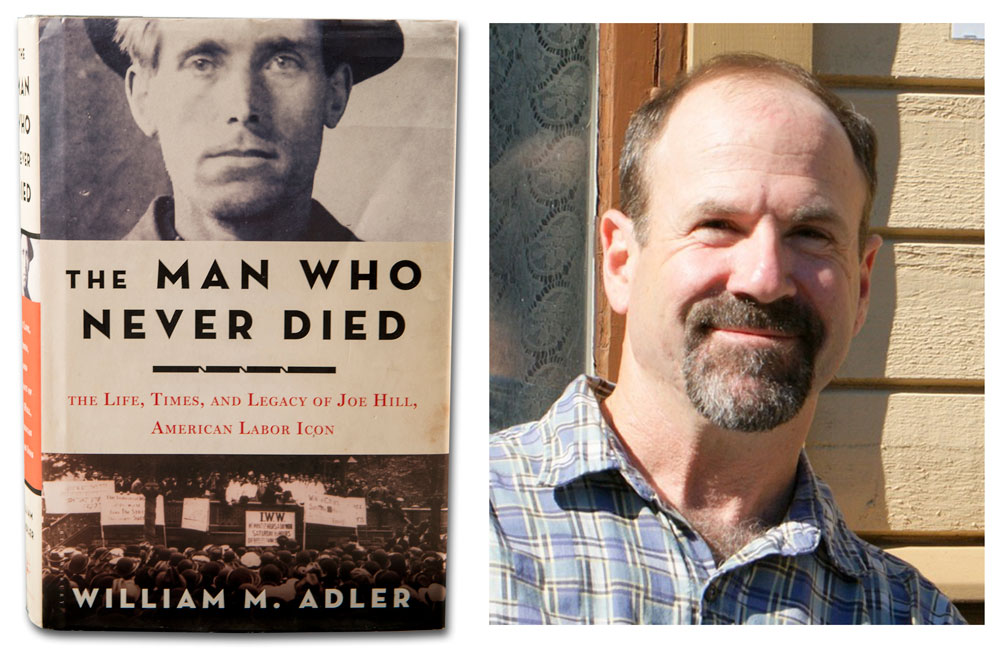

Denver author William M. Adler's 2011 book, "The Man Who Never Died," points to a likely alternative suspect, one who had a "startlingly violent and lengthy criminal career."

Adler, who will speak in Utah the week of events marking the centennial of Hill's still-controversial execution, believes the crimes probably were committed by lifelong criminal Magnus Olson. Adler spent about a year researching Olson, who used at least 20 aliases and was well-known to Salt Lake City police.

Olson, Adler said in a telephone interview, "seemed to fit the profile of a murderer, even though I couldn't say for sure that he in fact had committed the crime for which Joe Hill was executed."

Hill was convicted for the Jan. 10, 1914, murder of grocer John G. Morrison, who was shot in his downtown Salt Lake City store with his teenage son, Arling. A younger son said two gunmen burst in at closing time; no one was charged in Arling's death.

Gibbs Smith, author of the 1969 book "Joe Hill," praised Adler for turning up previously unknown information on Olson. Smith believes Hill would not be convicted today on the evidence available in 1914, and sees Hill, a songwriter for the Industrial Workers of the World, as a "true martyr" to labor.

"I think Adler's close to right," said Smith, owner of Utah-based publishing house Gibbs Smith. "I don't know if he's exactly right."

Others remain skeptical and expect debate about Hill's case to continue long past the 100th anniversary of his execution.

The Man Who Never Died

Denver author William M. Adler's 2011 book, "The Man Who Never Died." Photo of Adler by Randy Nelson.

Similarities between Hill and Olson

Hill and Olson both emigrated from Scandinavian countries, Hill born in 1879 in Sweden and Olson born in 1881 in Norway. Both were about 6 feet tall, weighed around 150 pounds, and had light brown hair, blue eyes and good teeth.

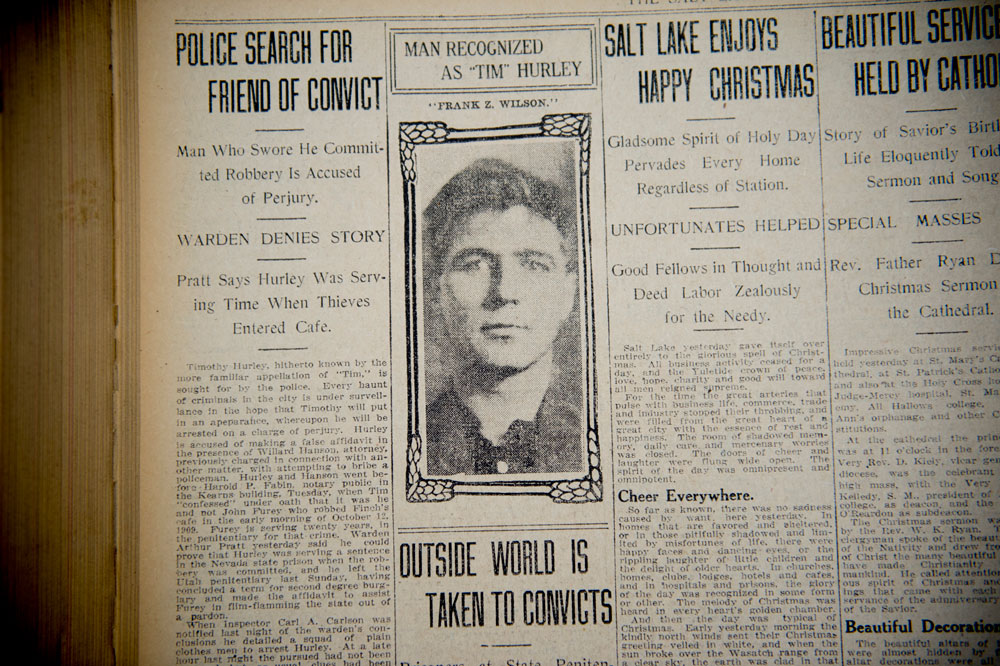

Newspapers reported immediately after the Morrison murders that Frank Z. Wilson — one of Olson's aliases — was a suspect in the killings. A detective even claimed that Hill had given a false name when he was arrested three days later and that he actually was Wilson.

Police had been tipped by a doctor who knew Hill had been shot on the same night of the murders; they suspected Arling had been able to return fire and hit Hill before dying.

Hill had no apparent motive and no eyewitnesses definitively identified him during trial. He initially said he had been shot in a dispute over a woman, but he refused to name the shooter, the woman or even where the argument happened.

Adler found a 1949 letter written by one of Hill's friends, who offered an explanation jurors and Utah authorities never heard. Hilda Erickson was the niece of the Swedish immigrant family in Murray with whom Hill and his friend Otto Appelquist lived, off and on, in late 1913. She was engaged to Appelquist by Christmas of that year, but soon changed her mind.

In a letter to a scholar who was writing a book about Hill, Erickson said Hill admitted to her that Appelquist had shot him. She didn't explicitly say the men fought over her that night, but she wrote that she once heard Hill tease Appelquist that he would steal her away.

Appelquist left town before Hill's arrest. Why Hill and Erickson remained silent about the alibi, even when it was clear Hill would be executed, is a mystery, Adler said.

"You can only speculate," he said, "and my speculation was that he insisted she not say anything."

Magnus Olson

If Hill's wound can be explained through Erickson's letter, then a more likely suspect, Adler argues, is Olson, who spent time in prisons in Utah and had several violent criminal acts to his name.

Olson's parents immigrated to Evanston, Ill., shortly before his third birthday, Adler found. They died when he was young and an uncle took him in. He began his criminal career as a juvenile, and from then on committed burglaries, robberies, assault, arson and attempted murder — and, Adler suspects, murder. He served time in nine states.

Olson came west and was in the Folsom State Prison in California in 1905, then was sent to prison in Nevada in 1908 after he and four ex-cons were arrested for looting railroad cars.

He entered the Utah State Prison in 1911 under the name Frank Z. Wilson for the theft of silks and furs from a rooming house and was released on Christmas 1912. On Jan. 10, 1914 — the day someone murdered the Morrisons — a prison guard saw him in Salt Lake City, according to a newspaper account.

About 40 minutes after the Saturday murders, a man boarded a streetcar about 10 blocks from the crime scene and rode to Main Street. The streetcar conductor later used police photos to identify the passenger as Wilson.

About 1 a.m., or about three hours after the murders, police officers stopped a man walking near the Morrison store. He gave his name as W.J. Williams, or W.Z. Williams, and told the officers he was out for a walk, though he was not wearing a coat and was shivering in the cold January night. The man also gave police false information about where he was staying and working.

Williams was arrested. Officers told reporters he resembled a suspect in the murders and said they believed he returned to the store to look for a wounded accomplice.

Frank Z. Wilson

This mugshot ran in The Salt Lake Tribune on Dec. 26, 1912. The names Frank Z. Wilson and Tim Hurley were aliases used by a career criminal named Mangus Olson. He was arrested as a suspect in the murder of Salt Lake City grocer John G. Morrison and Morrison’s son Arling before police pursued Joe Hill. Olson was not charged, and was instead turned over to authorities in Nevada, where he was wanted on burglary charges. Olson went on to become a bodyguard for Al Capone and was connected to Chicago's Valentines Day Massacre in 1929. In his 2011 book, “The Man Who Never Died,” historian William Adler offers a compelling argument that Olson could have killed the Morrisons. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

Based on newspaper reports and the transcript from the Hill trial, Adler writes that the man who gave his name as Williams was actually Wilson — or, to use what Adler believes is his real name, Olson. Save for the missing coat, he fits the description of the man who earlier boarded the streetcar. A police search of Williams' clothing, later on Sunday after his arrest, turned up a bloody handkerchief.

But Williams was apparently released on Monday and police didn't think he committed the murders, The Salt Lake Tribune reported on Tuesday, Jan. 13.

Police did rearrest Williams two days later, on Jan. 14, believing he might have knowledge about the killings. He again was held for two days and released, according to a book about the Hill case by Utah attorney Kenneth Lougee.

About two weeks after the murders, Wilson again was arrested in Salt Lake City and this time, he confessed to having robbed a boxcar in Elko, Nev., three days before. He was turned over to the Nevada sheriff.

Adler speculates Olson — as Williams or Wilson — may have paid off the detectives who questioned him about the Morrison murders, citing newspaper articles that said one of the officers was "infamous" for soliciting bribes.

A different view

Lougee is skeptical about seeing Olson as a prime suspect. He argues that police in 1914 used the word "suspect" to refer to people officers picked up because they might have information about a crime, not necessarily because they might have committed the act.

Lougee examined Hill's legal case for his book, "Pie in the Sky," which lambastes Hill's lawyers for shoddy work. He's not convinced Magnus Olson is Wilson's real name, and says court records he's examined show Wilson more as a bumbling burglar than a violent criminal.

"I certainly don't think the evidence is there that the guy is a psychotic killer," Lougee said in an interview.

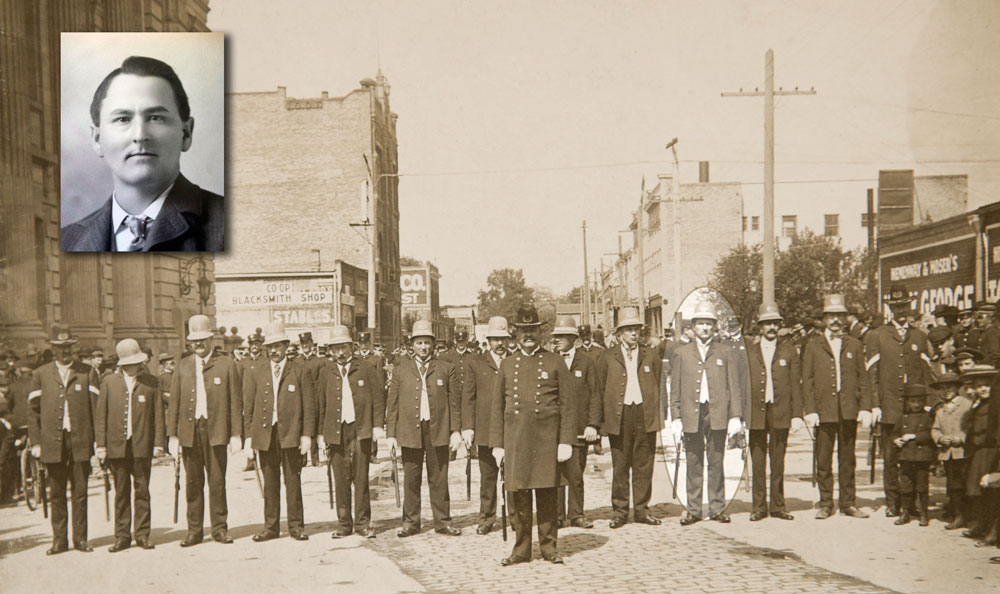

A trial attorney, Lougee said he would have looked for an alternative suspect in John Morrison's own fears. Morrison told his wife, a police captain, neighbors and a reporter that someone in the neighborhood — an unnamed person he had arrested when he worked briefly as a police officer — was trying to kill him.

"I don't think there's anything of more important relevance than the fears of the soon-to-be victim and the consistent story he's telling," Lougee said. But police already had their suspect: Hill.

John G. Morrison

Morrison, the fourth officer from the right, stands with other members of the Salt Lake City police department at the intersection of Main Street and Exchange Place, near what was then the U.S. Post Office and Courthouse. Photo courtesy of the Morrison family.

tharvey@sltrib.com @TomHarveySltrib

Comments

Comments