A circumstantial path to execution

District Attorney Elmer O. Leatherwood didn't have a murder weapon. He didn't have a motive.

He didn't even have a witness who would conclusively place Joe Hill inside the Salt Lake City grocery store where John G. Morrison and his son Arling were murdered.

His case was built on this reasoning: Someone who looked like Hill was in the neighborhood and inside the store on the night of Jan. 10, 1914. Someone was shot by young Arling Morrison. Hill was shot that night.

The jury followed his trail of circumstantial evidence to a guilty verdict — a conviction immediately assailed as unfair by Hill's supporters and scrutinized for the past 100 years. Criticism stretches from jury selection to rulings throughout the trial to jury instructions; popular theories have Hill framed by Mormons, by copper barons, by powerful opponents of unions like Hill's Industrial Workers of the World, known as the Wobblies.

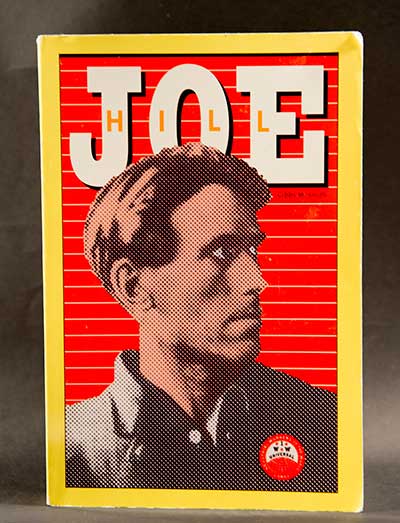

The trial was not as fair as it might have been, Utah historian Gibbs M. Smith concluded in his book "Joe Hill."

"But this raises the question," Smith wrote, "of whether any homeless migrant, Wobbly or not, would have received a fairer trial anywhere in America in 1914. The answer is probably not."

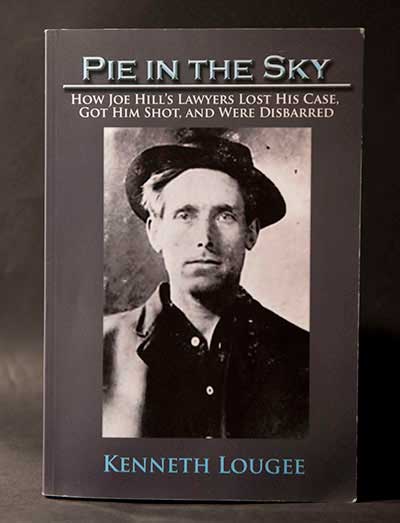

In "Pie in the Sky," his more recent legal analysis, Utah lawyer Kenneth Lougee decided the trial was "legal but not fair" — the assertion made by Hill's appellate attorney. Lougee blisteringly blames Hill's trial lawyers, Ernest D. MacDougall and Frank B. Scott.

"The blame for this result rests not upon the ‘copper bosses,' the Mormon Church, the judicial system, or any other conspiracy. It cannot be blamed on the prosecutor or the judge," Lougee wrote.

"In sum, MacDougall and Scott sealed Joe Hill's fate, and they did it to their client and themselves."

↕ Learn about the IWW

Who were the Industrial Workers of the World? Read more about the union and its presence in Utah here.

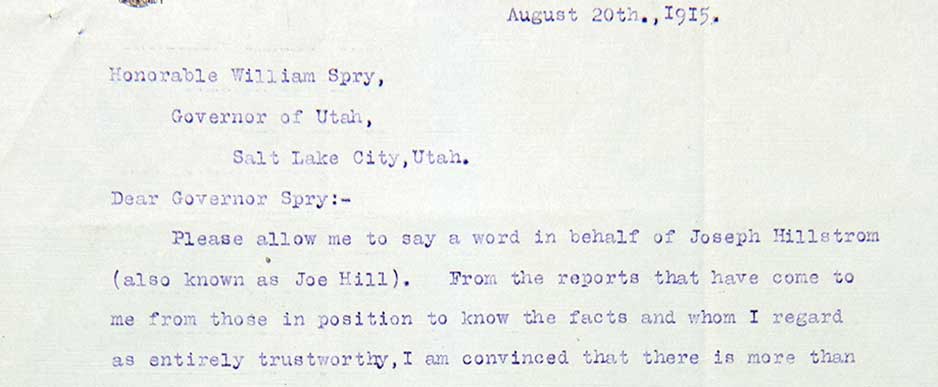

Letter sample

One on many letters sent to Gov. William Spry's office in regards to the trial of Joe Hill.

The issues

The jury was evenly split between Mormons and non-Mormons, according to a letter sent after the trial from Gov. William Spry's office. Among the issues jurors considered:

↕ Letters

Read letters sent to and from Gov. William Spry about the Joe Hill case here.

The eyewitness:

Merlin Morrison, then 13, was in the back of the store when his father and older brother were fatally shot. After Hill's arrest, Merlin went to observe him in jail. "As the light was dim [in the store] I could not get a lasting impression of the man's features, but Hill appears to be very much the same build as the man who entered the store first and whom I saw fire at my father," he said afterward, according to an account in The Salt Lake Tribune. He reportedly gave similar testimony at a preliminary hearing. But Hill later claimed Merlin "spoke his mind right out" at their meeting, saying, "No, that is not the man at all. The ones I saw were shorter and heavier set."

At trial, Merlin said he had not seen the first shot and whether it hit his father, and could only say that Hill's general appearance was the same as one of the killers, who both wore hats and had bandanas over their noses and chins.

↕ The Morrisons

The Morrison family's grief has echoed through five generations before finally finding peace.

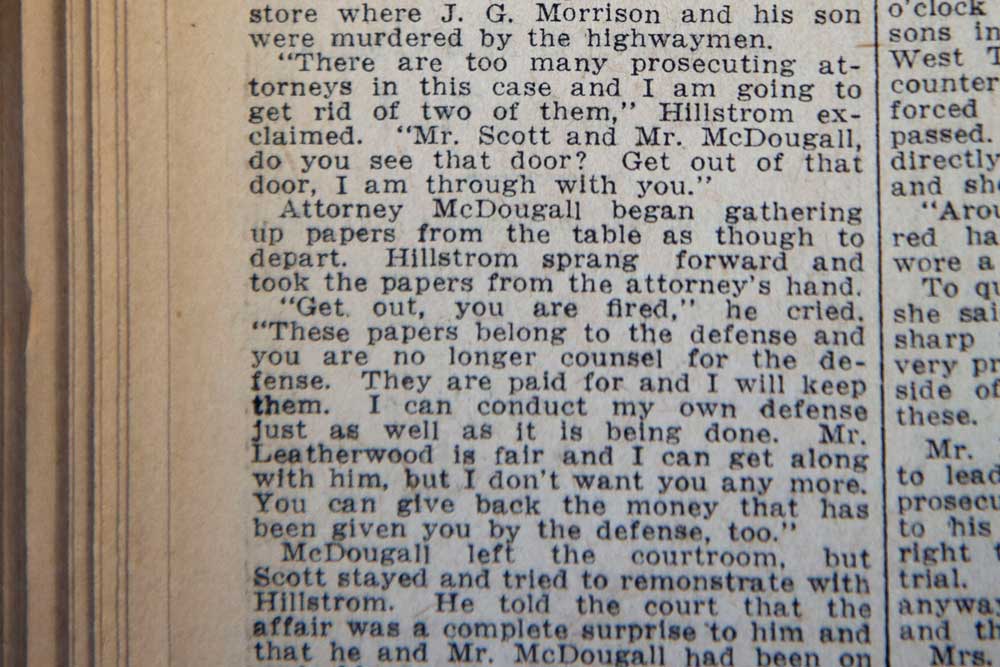

The outburst:

Frustrated by his attorneys' solicitous questioning, Hill stood on the third day of trial and asked to be heard. Without excusing the jury, Judge Morris L. Ritchie told him to go ahead.

"There are too many prosecuting attorneys in this case and I am going to get rid of two of them," Hill said, asking to fire his two lawyers and represent himself.

He later explained that his lawyers were failing to pin witnesses down about discrepancies between their testimony at the preliminary hearing (where he had represented himself) and at the trial, a point Lougee agrees with and finds deplorable. Hill objected through the testimony of two witnesses before Ritchie dismissed the jury to question him. After meeting privately with his attorneys, Hill agreed to have them join him in examining witnesses.

Outburst

On June 19, 1914, Joe Hill tried to fire his attorneys by rising to his feet and telling them to get out of the courtroom. His outburst occurred while the state chemist was testifying about blood spots found near the grocery store where John G. and Arling Morrison were fatally shot. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

The neighborhood witnesses:

At the preliminary hearing, Lougee writes, no witnesses mentioned seeing scarring on the faces of men walking toward or away from the Morrisons' store. Yet at trial, "several of the witnesses had recovered a recollection of a man with prominent scars," Lougee writes. Hill had scarring on his face from a treatment after a bout with tuberculosis in his native Sweden.

MacDougall and Scott, in Lougee's opinion, "simply let the witnesses get away with changing their story."

The witnesses agreed one of the men they saw was similar to Hill, but none definitely said it was Hill.

↕ The night of the crime

Read more here about the night of Jan. 10, 1914, when the Morrisons were murdered and Joe Hill was shot.

Arling's shot:

The attorneys sparred over whether Arling Morrison had actually fired the gun he grabbed from an ice chest. One of the several points of contention: The bullets fired by the intruders were all found in the store; Arling's bullet was never found. The bullet that struck Hill exited out his back.

Under the prosecution's theory, Hill later wrote sarcastically, the bullet went through a bandit, dropped to the floor and disappeared, leaving no mark. "If I should sit down and write a novel, I certainly would have to think up something more realistic than that, otherwise I would never be able to sell it," he wrote.

The gunshot wound:

The bullet hole in Hill's clothing was several inches lower than the entry wound. A defense doctor testified that Hill must have been holding his hands over his head when he was shot. Leatherwood suggested Hill may have been leaning over the store's counter to shoot Arling, and fate directed Arling's shot in return, leaving "the indelible mark on the murderer of his father." In one of his few comments on his wound, Hill wrote to the Utah Board of Pardons: "At the time when I was shot I was unarmed. I threw my hands up in the air just before the bullet struck me."

Hill's gun:

Hill claimed he had purchased his gun, a Luger, at a secondhand store in December. As a doctor treated his wound on the night of Jan. 10, the gun fell out of his clothing but remained in its shoulder holster. There were two physicians in the office that night; Hill later said he threw his gun out of the car as one gave him a ride home. That doctor testified the gun was similar to a .38 caliber Colt entered into evidence as the type of gun used to shoot John Morrison. The other testified he could not say.

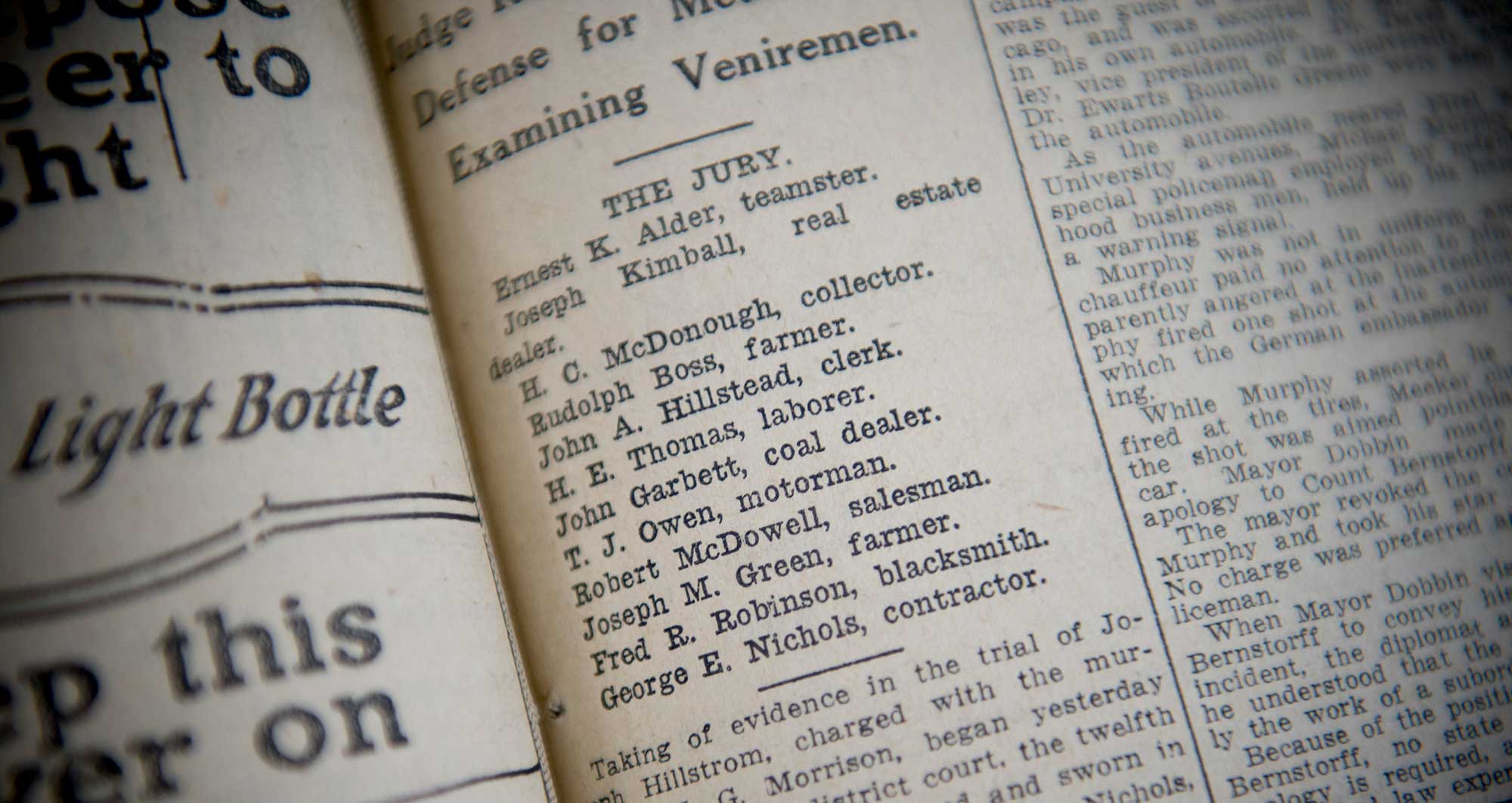

The Jury

These are the names of the jurors in Joe Hill's trial. The list appeared in The Salt Lake Tribune on June 18, 1914. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

What the jury did not consider

There were also issues the jury did not consider.

The revenge theory:

John Morrison had thwarted two earlier attempts to rob him, and in between those failed attacks, had briefly served as a police officer. He told several people in the months before the murders that he feared someone from the neighborhood wanted to kill him. Police first theorized that he and his son had been murdered by men seeking revenge. But the judge refused to admit testimony from a reporter who had interviewed Morrison about his fears.

A motive:

The assassins made no attempt to steal money from the store before fleeing. There was no evidence that Hill had known John Morrison and had any disagreement with him. On appeal, prosecutors insisted a motive was "clearly discernable," but didn't specify it. "It may have been robbery. It may have been revenge," their brief said. They also pointed out that the law didn't require them to prove a specific motive.

Hill's alibi:

Hill told the doctor who treated him that he had been shot in a dispute over a woman. He never named her or the shooter or the location. Hill's attorneys promised they would prove how he had been shot; in the end, Hill did not take the witness stand. Historians and others have speculated about his reasons ever since.

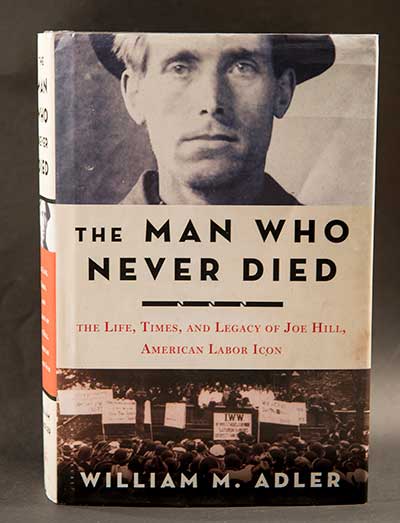

Author William M. Adler says a letter he discovered sheds some light. It was written in 1949 by Hilda Erickson, a Utah woman who had once been engaged to Hill's friend Otto Appelquist. Hill had once teased Appelquist about taking her away from him, she wrote, and that night, "Otto shot him in a fit of anger."

Erickson spoke with Hill the day after he was shot. She was in the courtroom the day Hill fired his attorneys, and he agreed to let them continue participating in the case after speaking with her. The story in the letter has its weaknesses, Lougee has written, but also appears credible.

Hill's confession:

Physician Frank McHugh, the doctor who treated Hill's gunshot wound, claimed decades later that Hill had confessed to him. In 1946, McHugh told a Cornell University professor that Hill said he had shot the Morrisons in self-defense as each reached for a gun. There was no evidence John Morrison, who had been moving potatoes when he was shot, ever reached for a gun.

Adler dismisses the confession story; Lougee says McHugh's failure to mention it in court could have been part of the state's trial strategy. Smith, the Utah author of "Joe Hill," adds it to the pile of "remaining mysteries" of the case.

'The acid of hate'

Hill was charged only with the murder of John Morrison, not Arling; police suspected Appelquist had been his accomplice but had been unable to locate him.

But Leatherwood, during his closing argument, called Hill a brute who shot out every "spark of life" from Arling Morrison.

Such a killer, Leatherwood argued, must be "some cold thing, some bloodless thing" whose veins were filled with "the acid of hate."

All three of Hill's defense attorneys — lawyer Soren X. Christensen had joined the team — offered arguments to support an acquittal. Christensen said the state hadn't proven that Hill had been shot at the Morrisons' store, or that Arling had even fired a shot. Scott contended that Hill's outburst the day he fired his attorneys demonstrated that Hill had the sensitive feelings of a musician and therefore could not be the ruthless killer the prosecution had described.

MacDougall's closing was more incendiary. Over the course of a four-hour monologue, he discussed evidence that had not been admitted and called the testimony from one neighborhood witness a "frame up."

He attacked Utah's court system and said Utah prosecutors did not believe in the presumption of innocence. Leatherwood, he said, did not care about justice.

Prosecutors, expected to make their case beyond a reasonable doubt, are given the final word.

Leatherwood said MacDougall's characterization of the trial made his blood boil with "keen resentment." And he seemed to make a reference to Hill's membership in the Industrial Workers of the World as he told jurors they had a duty to keep people safe from "parasites on society who murder and rob rather than make an honest living."

Verdict

On June 27, 1914, Joe Hill was convicted of killing John G. Morrison. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

The verdict

I have been shot a few times in the past and I guess I can stand it again.

Within hours of receiving the case on Friday, June 27, 1914, the jury reached its verdict. It was announced the next morning: Hill was guilty of first-degree murder, a capital offense.

At a sentencing hearing on July 8, Hill chose death by firing squad.

"I have been shot a few times in the past," he said, "and I guess I can stand it again."

A year later, Hill's appeal to the Utah Supreme Court failed; the justices ruled against him on July 3, 1915.

Hill's appellate attorney, Orrin N. Hilton, asked the Utah Board of Pardons to commute Hill's sentence; the board ruled against him on Sept. 18, 1915.

Amid international outcry, President Woodrow Wilson sent a telegram to Spry, asking for a postponement of the Oct. 1 execution date so the Swedish minister could have time to examine the case.

Spry reluctantly agreed. But when the stay expired shortly after Hill's 36th birthday, Spry rebuffed Wilson's second request.

Hill was executed by firing squad on the morning of Nov. 19, 1915.

Joe Hill on Instagram  Join the discussion about the trial

Join the discussion about the trial

Compiled and written by Sheila R. McCann