Agent L.M. reports

Undercover at Joe Hill's rebel funeral

She cried when she saw his body. Or at least she pretended to.

There he was, the poet shot four times in the chest by the state of Utah for a crime everybody in the room was certain he hadn't committed.

A mourner patted her on the shoulder. Just think about Joe Hill's bravery, the man told her, how Hill had faced the cowards who gunned him down at the state prison two days earlier. Take comfort in Hill's sacrifice and devotion to his friends.

But she wasn't one of Hill's friends. She was an undercover agent for the Intermountain Protective Service, under contract to Utah Gov. William Spry. Her assignment was to get inside Hill's funeral. Were Hill's supporters plotting to kill Spry? Were they building a bomb? There already had been threats on the governor's life and rumors about a plan to blow up his house.

Spry wanted the Industrial Workers of the World out of Salt Lake City, and Hill's service was an opportunity to plant an agent inside the union's ranks.

So he sent three operatives: No. 158, No. 129 and L.M.

158 and 129 got stuck outside.

L.M. made it in.

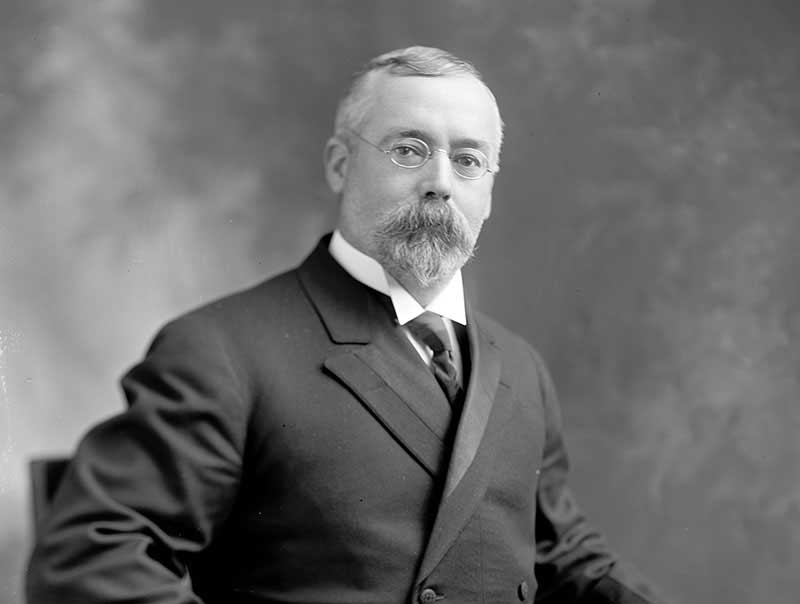

Gov. William Spry

Three of the undercover operatives hired by Gov. William Spry tried to infiltrate Joe Hill’s Salt Lake City funeral.

Raw hearts

The funeral was meant to be just for Hill's friends, a moment for the ones who had proclaimed his innocence, protested his death sentence and raised money for his defense. But Hill's murder trial had been such a sensation that thousands of people crowded West Temple outside O'Donnell's Mortuary, hoping for a glimpse of the man the governor had refused to save.

They weren't going to be let in until after his friends held his rebel funeral. But L.M. pushed her way through the crowd until she was pressed up against the front door. In a bit of luck, it opened and two men, friends of Hill, rushed in. She followed them.

Once inside, she told the young Swedish woman standing next to her how remarkable it was to be there. After all, she claimed, she had only been in Salt Lake City for two hours. She had come in on the noon San Pedro rail line from California to look for work and to pay her respects to Hill.

Impressed, the young woman asked if L.M. wanted to be introduced to Ed Rowan, the secretary of the local IWW chapter, and others in his inner circle.

Of course she did. Getting close to Rowan and his associates was the real reason she was there. The Swedish-born labor agitator in the coffin was, at this point, incidental.

Rowan and his men were very kind, a point she made in her report to the governor.

Instead of a prayer or song, the service opened with remarks from George Child, a member of the local IWW chapter who ran a furniture repair shop downtown. Child introduced a Denver IWW member who said he had been "shocked to the marrow" by the "permitted murder" of Hill. Even Hill's death had not been enough for the "raw hearts" of Utah authorities, who continued to publish untruths about him, the Denver man said.

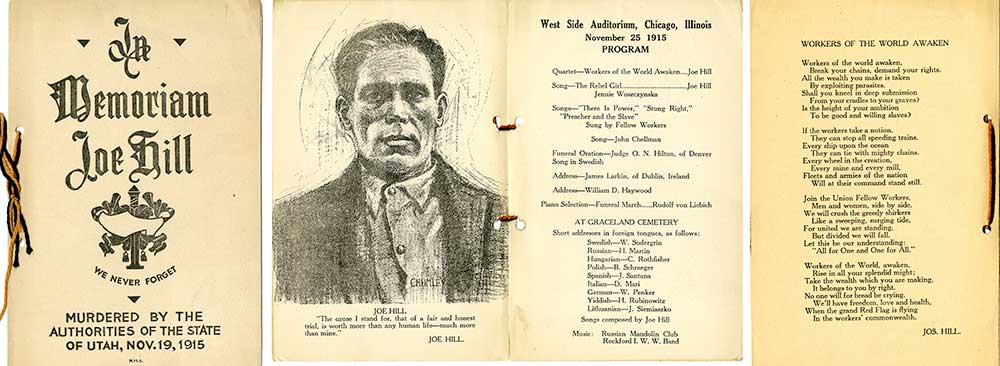

Funeral program

This is the program from Joe Hill's funeral in Chicago on November 25, 1915. Attorney Orrin N. Hilton was later disbarred in Utah for comments he made during his speech at the funeral. Photo courtesy Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives

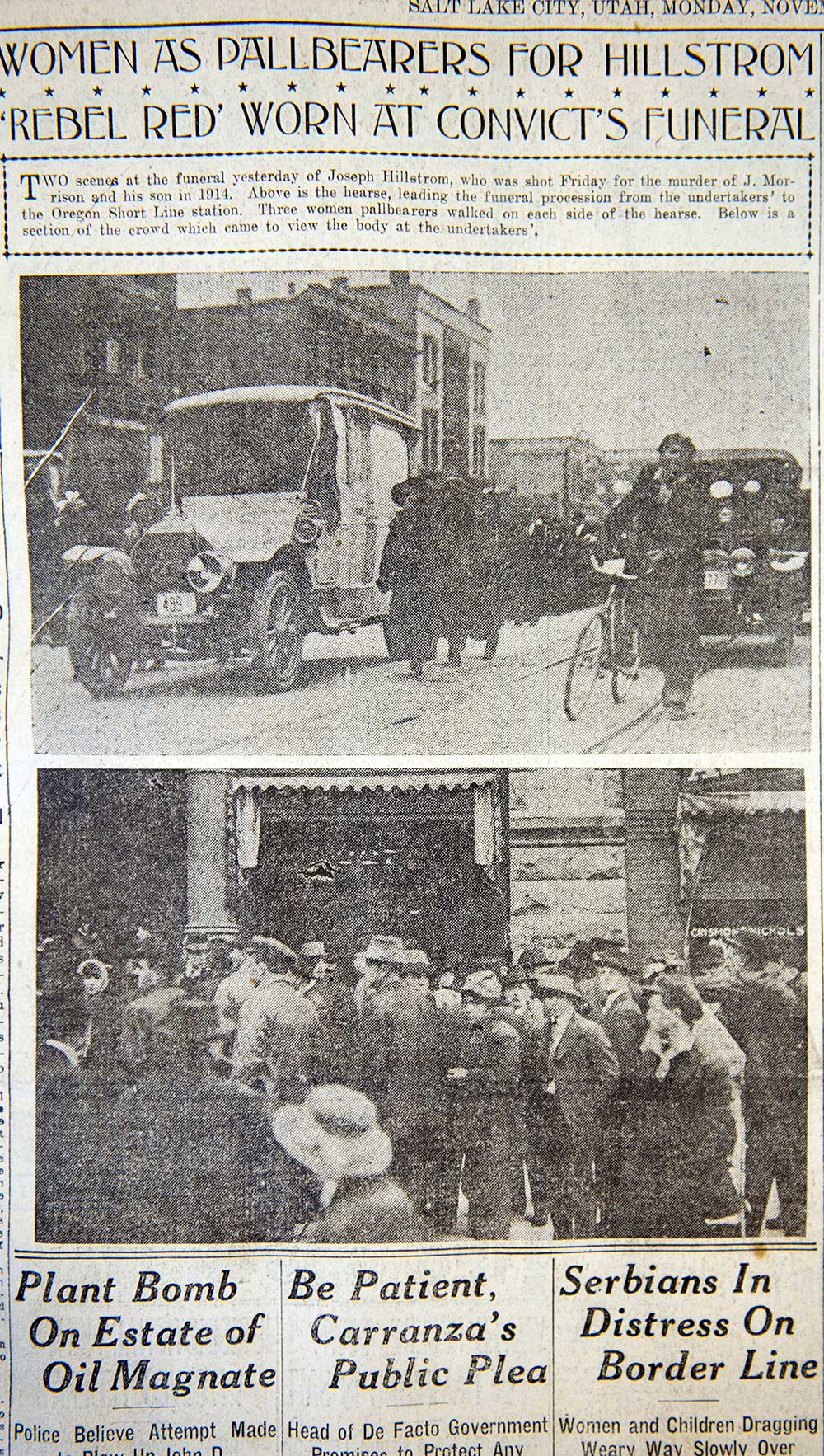

↕ News coverage of the Salt Lake City funeral

Joe Hill's funeral

The Salt Lake Herald-Republican published these two photos of Joe Hill's funeral service in Salt Lake City on Nov. 22, 1915. The top photo shows the hearse that carried Hill's body to a train depot. Six women, including his friend, Hilda Erickson, walked alongside as pallbearers. The bottom photo shows the crowd gathered outside O'Donnell's Mortuary, where Hill's service was held earlier in the day. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

He thanked Hill for "not wanting a minister to console him to the end," L.M. reported. "He brought out points to show that Hillstrom was more spiritual than any priest, minister or bishop in Salt Lake City."

He then read the poem Hill had written on the eve of of his death.

"My will is easy to decide, for there is nothing to divide," the verse began. "My kin don't need to fuss or moan, moss does not cling to a rolling stone."

Oscar Larson then spoke "with great emotion." As president of the Swedish Temperance Society, he eulogized his countryman in his native tongue. The young woman who had just introduced L.M. to Rowan now translated for her.

"She said that he ridiculed the Mormons," L.M. said, "and told how the Mormon missionaries who visited Sweden persuaded some of the natives to come to a country where love and freedom ruled; that when they did, they were shot and murdered by the authorities of that glorious State of Utah."

She said that he ridiculed the Mormons and told how the Mormon missionaries who visited Sweden persuaded some of the natives to come to a country where love and freedom ruled; that when they did, they were shot and murdered by the authorities of that glorious State of Utah.

Rowan told the crowd about the morning of Nov. 19, when he and others had gone to the prison to support Hill. The warden turned them away -- swearing at them and claiming Hill didn't want to see any of them. Rowan knew that was a lie.

He told them about Hill's only belongings, the few things the poem lamented would be easy to divide. There was a silk handkerchief. Rowan was keeping that. There was a photograph of a boy on a pony. It was the son of Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Hill's "Rebel Girl," the inspiration behind his song. The photo was to be given to the other woman in Hill's life, Hilda Erickson.

L.M.'s report referred to Erickson as one of Hill's "closest friends." Many wondered whether she was the woman Hill was fighting over with a friend on the night he was shot, and had since refused to name.

Prosecutors, of course, had argued Hill was shot by teenager Arling Morrison after Hill fatally shot the boy's father, John G. Morrison, in their Salt Lake City grocery store.

Rowan again read Hill's will.

"My body? Oh, if I could choose,

I would to ashes it reduce

And let the merry breezes blow

My dust to where some flowers grow

Perhaps some fading flowers then

Would come to life and bloom again

This is my last and final will

Good luck to all of you, Joe Hill."

It was time to escort Hill's body to the train station for his funeral in Chicago. As mourners marched towards the Oregon Short Line depot, they sang Hill's famed "There is power in a union."

After a singing a few more songs at the depot, "People drifted this way and that all with the name of Joe Hillstrom on their tongues," L.M. wrote in her report.

↕ See Joe HIll's last will

Last will

This poem was written by Joe Hill on November 18, 1915, on the eve of his execution in Salt Lake City. The poem was given to local IWW chapter leader Ed Rowan who read it at Hill's funeral in Salt Lake City. Photo courtesy Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Archives

There Is Power in a Union

One of Joe Hill's most enduring recruiting songs. After his execution, the song was sung at his funeral in Salt Lake City and again at his funeral in Chicago. The song is performed here by Folk Hogan in Salt Lake City's Sugar House Park, near the site where Utah's state prison once stood and where Hill was executed by a firing squad on Nov. 19, 1915.

Gaining trust

L.M. had started to leave when two of the Rowan associates she met at the funeral — Paul Roudine and a Mr. Hedberg — offered to help her find a place to stay.

She claimed one of Hill's friends had already recommended a boarding house at 402 E. 200 South. Other reports show another undercover operative had been staking out the boarding house a week earlier.

Hedberg was surprised — that was where he had been staying for the week or so that he had been in town, helping to coordinate IWW telegrams and meetings. L.M. took a room two doors down from him and would spend more than two weeks reporting on his movements and visitors.

As L.M. left for dinner, Hedberg apologized for asking but wondered if he might join her.

As they walked, the conversation inevitably turned back to Hill, and more specifically to Spry's desire to chase "all undesirables" from the state.

"We don't want to do anything rash," Hedberg told L.M. "That would not bring back the life that has been killed, but the governor better live and let live. That is our motto, we only want justice. While I know the governor can ship us all out, I hope for all concerned he won't try it."

During dinner at the Star Cafe on State Street, "Everyone in there was talking about the execution of Hillstrom, some being in sympathy and others declaring that the governor did the right thing. None of them seemed radical," L.M. said.

After dinner, Hedberg offered to take L.M. to church or a picture show. She asked him to take her to an IWW meeting instead.

He said none was planned, but led her to a little house on 600 East between 200 and 300 South.

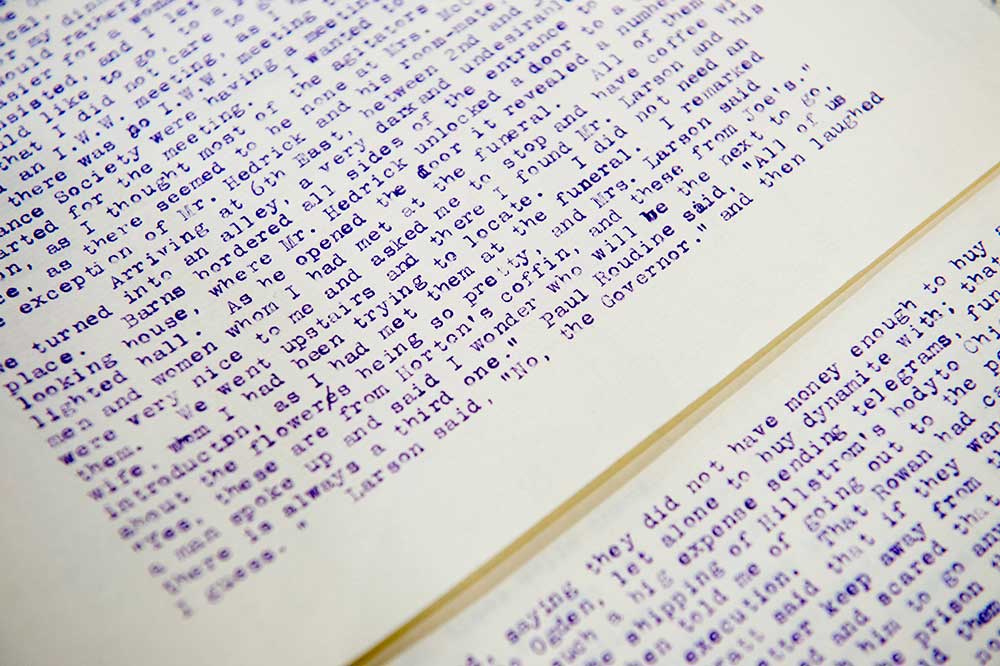

L.M.'s report

This report was written by a female agent known only as L.M. It details her work on November 21, 1915, as she goes undercover at Joe Hill's Salt Lake City funeral, gets close to IWW leaders and starts what would be about two weeks of work keeping tabs on members of the cities radical community. It is part of a 80 pages of reports written by a dozen agents working for the Intermountain Protective Agency as they gathered information for Governor William Spry. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

Women cried, men raged

The home sat at the end of an alley and was a "very dark and undesirable looking place." She stepped into a dimly lit room where she recognized a number of people from the funeral earlier in the day.

They went upstairs and found Oscar Larson, the leader of the Swedish Temperance Society, and his wife, sitting with other men and women. L.M. was pleased, noting, "I wanted to get in touch with Larson, as I thought most of the agitators would be at his place."

L.M. commented on the beautiful flowers in the room. "Yes, these are from Horton's coffin," Mrs. Larson said. "And these from Joe's."

Roy Horton, a fellow IWW member, had been killed a few weeks before Hill. He was shot three times in downtown Salt Lake City after mouthing off about law enforcement. The man who killed Horton was later acquitted.

Roy Horton. Joe Hill.

Roy Horton's headstone

Roy Horton was an Industrial Workers of the World member in Salt Lake City. Unarmed, he was shot and killed on on Oct. 30, 1915, in downtown Salt Lake City by a former police officer, who was eventually acquitted.

A man in the room asked who would go next. These things always happen in threes, he observed. "All of us, I guess," Roudine responded. "No, the governor," Oscar Larson said. Then he laughed. An assassination just wasn't plausible. Sending telegrams, arranging Hill's funeral and shipping his body to Chicago had been so expensive that supporters "did not have money enough to buy a telegram to Ogden, let alone to buy dynamite with." The group talked about going to the prison with Rowan to see Hill on the morning of the execution. As Hill's friends, thwarted by the warden, waited outside, the sun rose and they began to be hopeful. Perhaps Spry had given in to President Woodrow Wilson's request for a stay and Hill would be spared for a short time longer. Then shots rang out from behind the walls. "The women cried," L.M. reported, "and the men raged." The group then went downstairs for a society meeting, singing, reading and serving coffee. It was "very enjoyable," L.M. said, "and without threats of destruction to any buildings or persons." Hedberg walked her back to the boarding house. She stayed awake in her room until she could hear him snoring. "I then discontinued," she said, "it being 11 p.m."

jharmon@sltrib.com Joe Hill on Instagram  Join the discussion

Join the discussion