Staying silent

Why didn't Joe Hill save himself?

It's one of the most vexing mysteries in the story of Joe Hill's 1915 execution: Why didn't Hill just tell Utah authorities who shot him, revealing the alibi that could have saved his life?

Facing an international outcry, Gov. William Spry promised that Hill could walk out of prison a free man — if he would only back up his claim that he had been shot somewhere other than inside the grocery store where a father and son had been gunned down.

Virginia Snow Stephen, the daughter of a late LDS Church president, was one of Hill's most prominent champions. But almost 35 years later, she remained baffled.

"I cannot think that Joe Hill himself could be such a confounded egotistical stubborn fool as to be silent about this," the remarried Virginia Filigno wrote to friend and researcher Aubrey Haan in June 1949.

Yet in the same letter, she describes the chilling atmosphere of fear and threats that surrounded union workers and immigrants in Salt Lake City.

Perhaps the question should be flipped: Why would Hill, or any supporters who may have had clues to his alibi, have trusted Utah's criminal justice system and others in power enough to come forward?

Before his arrest, Hill told a doctor he "got into a stew" with a friend who shot him over a woman, but refused to say more. When he was first jailed, he urged his union, the Industrial Workers of the World, not to get involved. He got angry with his attorneys when they pressed for details about the alibi.

The romantic legend that Hill remained silent throughout his trial and appeals so that he could safeguard a woman's honor doesn't ring true for University of Utah labor historian Matthew Basso.

Hill's radical union had been under attack by local, state and federal officials across the West for a decade, Basso points out. Hill also was an immigrant, living in Murray's impoverished, insular Swedish community, where some felt misled or betrayed by the LDS Church.

Like the tensions underlying today's protests in Baltimore, Ferguson and other cities, many immigrants and IWW members felt marginalized and had a "deep, deep distrust" of police. Hill believed police in California had trumped up a vagrancy charge against him in retaliation for his role in a strike there, and he and others may have felt "justice is not going to be done here," Basso said.

Hill likely would've wanted to protect his friends — perhaps even the man who shot him — his fellow workers and the Swedish family who had taken him in, Basso said. He lived under a code that said his role "is to protect the family, is to protect the movement, to see politicians and authorities as an obstacle to the future these IWW members were hoping for."

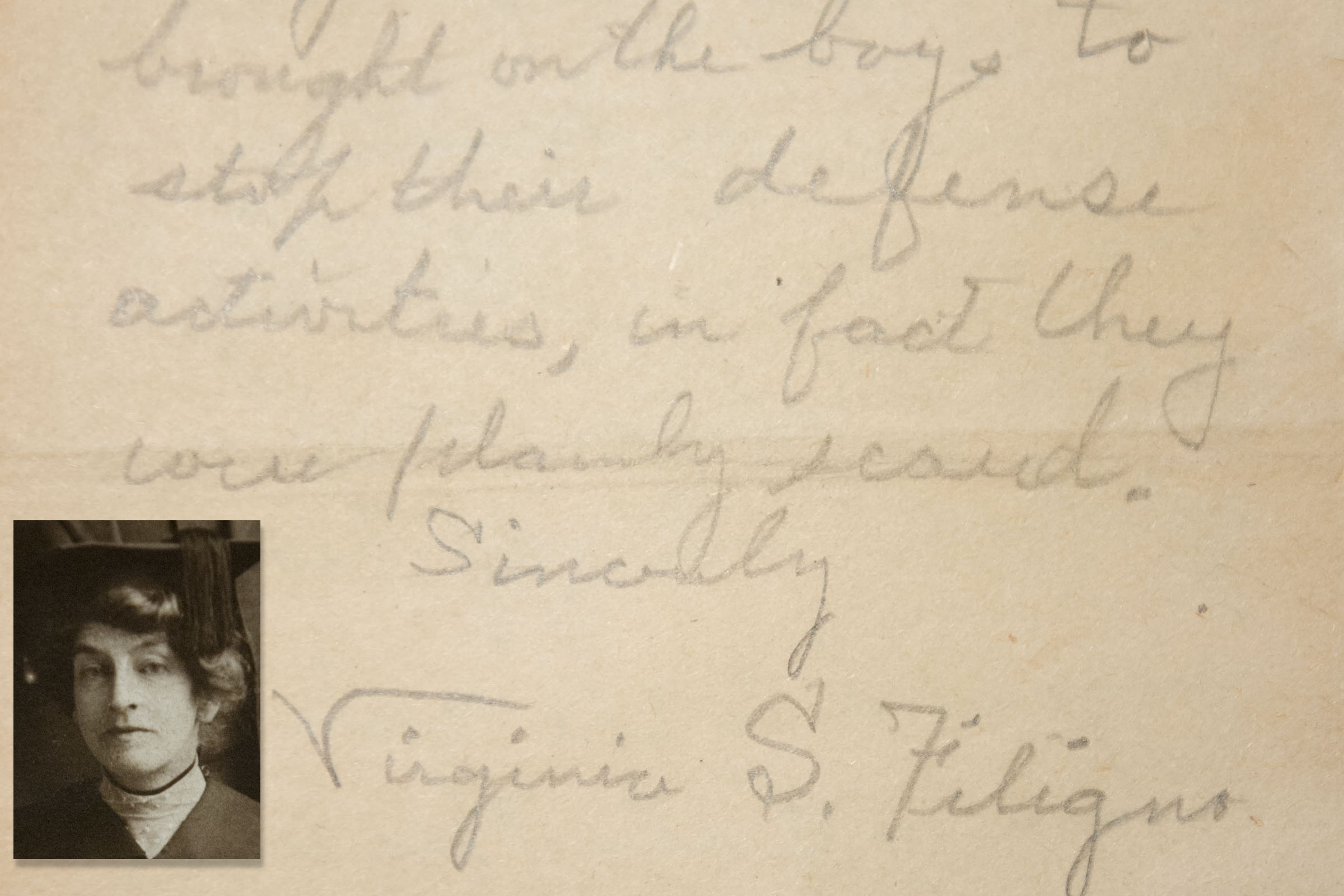

Filigno's letter is one of several documents recently obtained by The Salt Lake Tribune from Haan's daughter, Mary, and it describes how Hill's IWW friends felt they were in danger — and in need of such protection.

IWW leader Ed Rowan, a member of the committee fighting to save Hill's life, "made plain to me that a strong pressure had been brought on the boys to stop their defense activities," Filigno wrote; "in fact they were plainly scared."

One other thing that influences my thinking is that an interview with Ed Rowan made plain to me that a strong pressure had been brought on the boys to stop their defense activities, in fact they were plainly scared.

Virginia Snow Filigno letter

In this letter from Virginia Snow Filigno, she tells Aubrey Haan that Ed Rowan and members of the Joe Hill Defense Committee were "plainly scared" due to pressure put on them to stop their efforts to help Joe Hill. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

A tense relationship

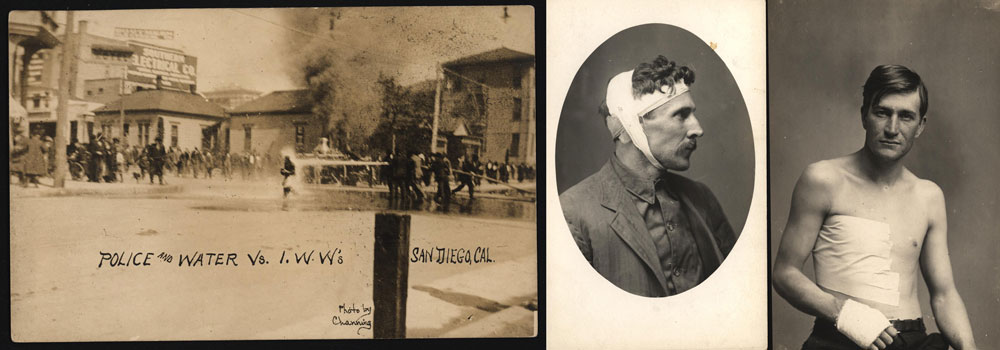

A riot in Salt Lake City four months before Hill's arrest illustrates how IWW members were treated by the law, industry and in public opinion around the West.

On Aug. 12, 1913, about 500 people gathered for a downtown rally that began peacefully. The crowd sang Hill's "Mr. Block," a sarcastic ode to a worker who naively believed his employer, politicians and the law would watch out for his interests.

But gunfire broke out after security guards for the Utah Construction Company attacked IWW speakers.

"A free-for-all fight occurred, broken only by the fire department drenching the crowd with streams of water," IWW member George Child said in a 1914 description, according to Haan's notes. Although there was no question that the company guards had initiated the conflict, only IWW members were arrested. The construction company had been targeted in an IWW strike earlier that year.

Axel Steele, a company guard who led the attack, was shot, but not seriously injured by IWW member Tom Murphy. Murphy claimed self-defense but spent a year in jail for shooting and injuring Steele and others.

The city's police chief banned IWW street meetings and Steele was considered a hero, winning sympathy by "claiming that his attack on the IWW was an act of patriotism," author Gibbs Smith wrote in his 1969 biography of Hill. And Utah was part of a bigger picture, Smith said in a recent interview.

Since its founding in 1905, the IWW had been involved in strikes and in often-violent fights with various city governments for the right to even hold a meeting. IWW members clashed with authorities in Spokane, Wash., and Missoula, Mont., in 1909; Fresno, Calif., in 1910; Aberdeen, Wash., in 1911; and Denver and Wheatland, Calif., in 1913.

The free-speech fights in San Diego in 1912 were among the IWW's longest and most violent; members were beaten and some were killed. In his 2011 book, "The Man Who Never Died," author William M. Adler confirmed Hill was in the San Diego area during that time.

IWW member Charles Hanson described being forced onto a train with other union members, then taken out of town where they were met by a mob of vigilantes. Hanson said the union members were severely beaten by intoxicated men brandishing wagon-wheel spokes and other items as clubs.

California Gov. Hiram Johnson sent to San Diego an investigator who was critical of IWW actions.

But he also decried the brutality of their attackers, writing, "Surely, these American men, who as the overwhelming evidence shows, in large numbers assaulted with weapons in a most cowardly and brutal manner their helpless and defenseless fellows, were certainly far from ‘brave' and their victims far from ‘free.'?"

San Diego free speech fight

Police use a fire hose on a man on March 10, 1912, during the San Diego free speech fights. Industrial Workers of the World members ignored a city ordinance that barred its street meetings from a large area of the city, claiming the law violated their free speech rights. Police and others responded with brutal violence. Vigilantes took IWW members outside of the city, where mobs would beat the so-called Wobblies with a variety of weapons, and some were killed. An investigator dispatched by California Gov. Hiram Johnson condemned the actions of both sides. The men on the right were both victims of the violence during the fight. Photos courtesy University of Michigan Library, Special Collection Library, Joseph A. Labadie Collection.

'Doctrines of hate'

On the first day of November 1915, Salt Lake City was on edge. Hill was scheduled to be executed in a little less than three weeks; rumors circulated that the IWW was planning to blow up the governor's residence and that 500 men were going to storm the prison and free Hill. (Neither proved to be true.)

Prominent community leader and former federal Indian agent Howell Myton bailed out of jail that day just in time to have lunch at the local Elks Club, where he was greeted with supportive handshakes in a hero's welcome.

The day before, he had killed a Salt Lake City IWW member named Roy Horton.

The official story was that Horton had been standing outside a bar on 200 South in the early morning hours of Oct. 31, talking with his friends about the police. Horton reportedly said, "Any man who wears a star is a dirty _______."

While newspaper reports left out the objectionable word, whatever he said angered Myton, who was passing by and confronted Horton. "This was meant for you or any other _______ who will wear a star," Horton told him.

"I'll kill you for that," said Myton, who went to his room in the Walker Building, got a gun, came back out on the street and shot Horton three times. He argued self-defense and was acquitted.

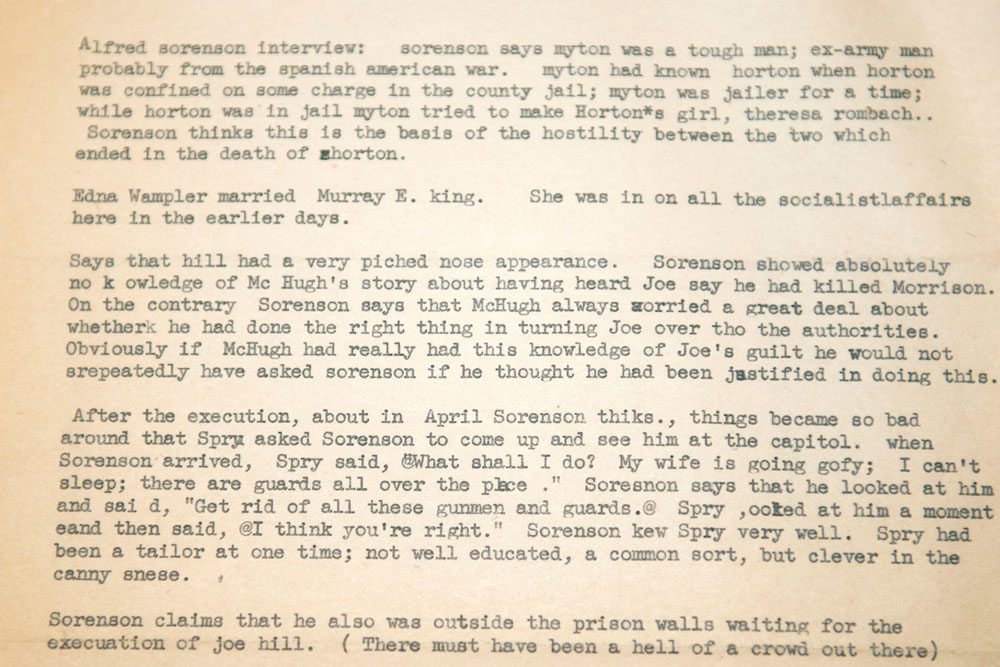

However, Haan learned of a substantially different version of events.

Alfred Sorenson, a Salt Lake City jeweler who was a member of Hill's defense committee, told Haan that Myton had previously made advances towards Horton's girlfriend while the IWW man was in jail.

↕ Alfred Sorenson interview

Alfred Sorenson interview

These are notes Aubrey Haan made of an interview with Alfred Sorenson. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

"That's new," Smith said. If others in Hill's IWW circle believed police and prosecutors were covering up the facts, it was another reason to distrust the system.

The Salt Lake Herald-Republican said Horton had earned his fate.

Horton's death, it opined, was just the "natural, logical sequence of the doctrines of hate that have been preached by agitators in this community."

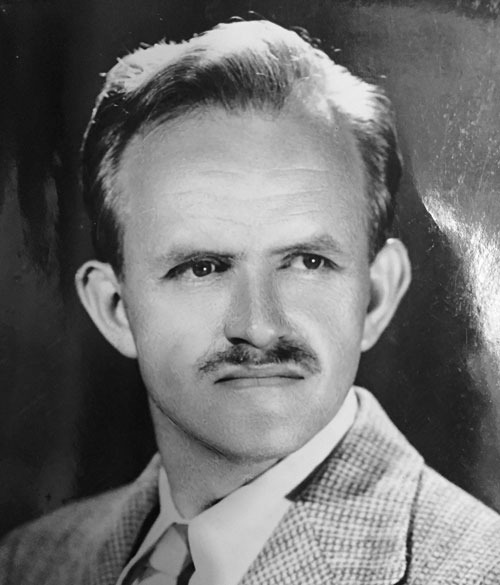

The death of Roy Horton

Roy Horton was an Industrial Workers of the World member in Salt Lake City. Unarmed, he was shot and killed on on Oct. 31, 1915, in downtown Salt Lake City by a former police officer, who was eventually acquitted. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

A ‘terrible suggestion'

Hilda Erickson claimed she always knew exactly who shot Hill: her former fiance, Otto Appelquist. Erickson told her story to Haan in 1949, but publishers rejected Haan's manuscript, and the letter remained unknown until Adler brought it to light in his book.

Appelquist and Hill were staying, off and on, with Erickson's uncles in Murray. She had broken off the engagement a week before Hill was shot, and she wrote, "I heard Joe tease Otto once that he was going to take me away from him."

Erickson said Hill told her, "Otto shot him in a fit of anger. He was sorry right after and carried him" to a doctor for treatment. "I saw Joe every Sunday afternoon in the Salt Lake jail," Erickson wrote. "I would speak English to him, but he would talk Swedish to me in a low voice and tell me not to say a word because he was innocent of the Morrison case, therefore the State of Utah could not prove him guilty."

In another letter, she reiterated that Hill "did insist" that she not talk about the case. Filigno was skeptical.

"I can only think that your letter may have suggested to her the idea of making up a romantic story with herself as heroine," Filigno wrote to Haan. Filigno seems to debunk the idea that Erickson's honor would have required her and Hill to remain silent, and it doesn't appear in Haan's other correspondence, either.

I can only think that your letter may have suggested to her the idea of making up a romantic story with herself as heroine.

Even if Erickson's story was true, Filigno said, "any common, ordinary run of the mill girl" would have spoken up "at the time everybody was aware Joe's life was at stake, would have made some effort to save him, as it was so plain what effect her story might have had."

Filigno also objects that such a secret would have been impossible to keep: "And besides the whole family must have known all about it."

Then her mind turned to what she called "one terrible suggestion." She realized, she wrote, "that as this story would of course help the defense, the whole outfit at that den at Murray, might have been by means of intimidation and threats, paralyzed with fear, into complete silence."

Filigno and Erickson

Virginia Snow Stephen, later Virginia Snow Filigno, and Hilda Erickson are seen sitting together in this undated photo. Both women were involved in the events surrounding the execution of Hill on November 19, 1915. Photo courtesy Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

The reason for Hill's silence was clear to fellow Swedish immigrant Olaf Lindegren, who lived in Murray and knew Hill, Appelquist and Erickson. And it wasn't Erickson's honor that was relevant to Lindegren when he decided to explain the situation to Spry just weeks before Hill's execution,

Instead, after describing the relationships between the men and Erickson's relatives, he said: "As Hillstrom and this family were strong friends, fraternity brothers and countrymen, it is only natural to suppose that Hillstrom will not bring them into the case at any price."

Lindegren urged the governor to investigate, suggesting, "with great precaution enquire [sic] of the girl Hilda."

It's impossible to know all of the reasons for Hill's silence. But as his execution drew closer, many historians believe Hill had embraced his fate, perhaps believing he could do more for the IWW dead than he could alive.

Adler writes that before Hill's death, "He was the good soldier in the class war; afterward, he became one of the most decorated there ever was."

Publicity generated by Hill's imminent death had given his life meaning, Adler writes. "The cause needed a martyr, someone to incite his fellow workers, to inspire them not to mourn but to organize, and he cast himself in that swaggering role."

Hill said he knew the stakes and accepted them.

Shortly before his execution, he stood before Utah's Board of Pardons and said, "Gentlemen, the cause I stand for, that of a fair and honest trial, is worth more than any human life — much more than mine."

jharmon@sltrib.com @JoeHill_history

Join the discussion

Join the discussion