Joe Hill

The Making of A Martyr

Joe Hill was tied to a chair. Blindfolded. A small target was pinned to his chest. "Let it go, fire," he yelled.

Rifles protruding from the blacksmith shop at Utah's state prison obliged. Three of the bullets pierced his heart. The fourth went a little wide.

Though that was the last thing he said, it wasn't the last thing people would hear from Joe Hill.

As the centennial of Hill's execution on Nov. 19, 1915, approaches, his critiques of capitalism and the "greedy master class" echo in Occupy Wall Street and in Bernie Sanders' attacks on America's income inequality.

The influence of his protest music, written for the Industrial Workers of the World, can be traced through Pete Seeger and Woodie Guthrie to Bob Dylan to Bruce Springsteen to the rock group Rage Against the Machine.

A Swede who labored around the West, he sought justice for poor immigrants working at hazardous jobs, an issue that resonates today.

Lingering controversy over his execution for the murder of a Salt Lake City grocer has created an enduring, intriguing mystery and reflects ongoing debate about the death penalty.

Utah publisher Gibbs M. Smith, who wrote a 1969 biography about Hill, says the parallels between 1915 and 2015 and the question of whether Utah executed an innocent man have kept Hill's story alive.

Hill "came to symbolize the struggle of the working people against this oligarchy of capitalists," Smith said.

"He symbolized somebody who stood up against injustice. And he symbolized somebody without any real power standing up against guys with power, just by his wits."

Joe Hill

This is one of Joe Hill's booking photos, dating from when he was moved from the Salt Lake County jail to the state prison after his conviction in the death of John G. Morrison. Morrison and his son Arling were fatally shot in January 1914. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune.

He symbolized somebody who stood up against injustice. And he symbolized somebody without any real power standing up against guys with power, just by his wits.

Leaving Sweden

The prison yard in what is now Sugar House Park in Salt Lake City was a long way from Gävle, Sweden, where Hill was born Joel Hägglund in 1879.

He learned to play music and paint in the small port town, where he also began to learn English while working on ferries with his brother Paul. After their father, Olof Hägglund, died in 1887, his children left school to work to support the family.

At the age of 9, Joel worked in a rope factory.

Their mother, Margaretha Catharina Hägglund, died In 1902. Joel and Paul left their four siblings and, like millions of other hopefuls, immigrated to the United States . When Joel arrived in the Land of Opportunity, he got a job cleaning spittoons in a bar in New York City. Disillusioned, he went to Chicago, where he was blacklisted for trying to start a union.

This may be when Joel Hägglund became Joseph Hillstrom. His new name wouldn't have been on blacklists.

Hillstrom headed West, where he would work as a longshoreman and a laborer, as a mechanic and as a miner.

He was in San Francisco during the 1906 earthquake, then headed to the Northwest. He was in Tijuana in 1911, where he and an army of other transient workers took part in the Mexican Revolution. He was in San Diego during a 1912 free-speech fight. But 1910 was key. That appears to be the year he joined the Industrial Workers of the World.

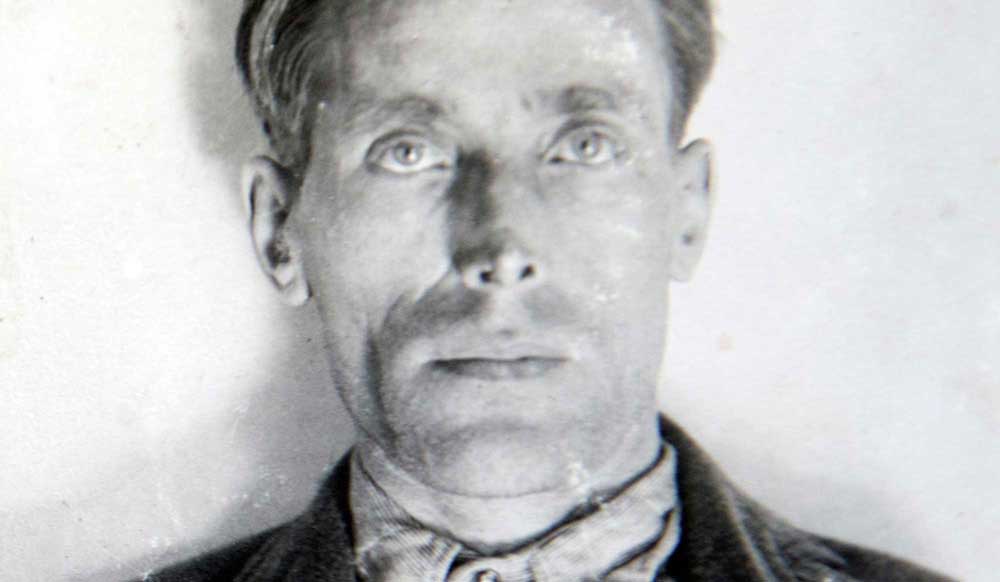

Hill's family

This portrait shows the family of Joe Hill, born Joel Hägglund, circa 1890. His mother, Catharina Hägglund, is surrounded by her children. Joel is standing on the left. To Joel's right are his brothers Ruben, Efraim and Paul. His sister Ester sits in their mother's lap while Judit is seated next to Catarina. Photo courtesy The County Museum of Gävleborg, Sweden.

Joining the singing union

The radical union was a good fit for Hillstrom. The IWW, also known as the Wobblies, was made up largely of immigrants and led by influential left-wing radicals. Their stated goal was to break people free from the exploitation of capitalism and build a new society, where workers owned the factories, mills and mines.

Its members rallied and organized strikes, work slowdowns and, at times, more damaging sabotage. Another tactic, used in cities like Spokane and San Diego: Wobblies would travel to cities for free-speech protests and undergo arrests until the jails were full and the court dockets were clogged.

They were also a singing union, and Hillstrom was a musician. He was soon writing "rebel songs" for his fellow Wobblies.

And we're going to find a way, boys. Shorter hours and better pay, boys. We're going to win the day, boys, where the Fraser River flows.

The IWW first published one of his songs in the 1911 edition of the "Little Red Songbook." The song, credited to Joe Hill rather Joseph Hillstrom, was "The Preacher and the Slave." A few months later, "Casey Jones — the Union Scab" would be published.

The songs soon became IWW anthems and made Hill a well-known union name. In 1912, Hill was in San Diego, San Francisco, Canada and San Pedro. In British Columbia he wrote a song called "Where the Fraser River Flows" for striking railroad construction workers.

The chorus ended with the lines, "And we're going to find a way, boys. Shorter hours and better pay, boys. We're going to win the day, boys, where the Fraser River flows."

Before the end of the summer, he was back in San Pedro, where he was elected secretary of an IWW-led longshoreman's strike. The strike was defeated, the Wobblies were blacklisted, and Hill would eventually spend 30 days in jail on a vagrancy charge. He believed the charge was retribution for his role in the strike.

↕ Riot in downtown Salt Lake City

Shortly after Hill got out of jail, he was on his way to Utah, arriving in the state capitol at a rather inopportune time for a wobbly. Hill's union had just been involved in a riot in the heart of downtown Salt Lake City.

Several weeks before Hill arrived in Utah, IWW members had prevailed in a strike against the Utah Construction Company on a railroad project in Spanish Fork Canyon. While the IWW won, it was not before several strikers wound up in jail in Provo, Utah, after a skirmish with private security guards.

On August 12, 1913, one of the men, a man named James F. Morgan, had just gotten out of jail in Provo and was speaking at an IWW rally in downtown Salt Lake City. Just as the rally was starting, a man who had helped arrest Wobblies in Spanish Fork Canyon led an attack on the rally. As the fight progressed, one of the IWWs pulled out a pistol and started shooting. A riot ensued. The attackers were hailed as heroes in all the papers the following day and Wobbly popularity in the Mormon capitol reached a new low.

IWW protest

Joseph Ettor, a prominent organizer with the Industrial Workers of the World, speaks to a group of striking barbers in New York City on May 17, 1913. Photo courtesy Library of Congress.

Into Utah

Shortly after Hill got out of jail, he headed to Utah, where IWW members had just been involved in a riot in downtown Salt Lake City.

IWW members had prevailed in a strike against the Utah Construction Company on a railroad project in Spanish Fork Canyon. But several strikers wound up in jail in Provo, Utah, after a skirmish with private security guards.

On Aug. 12, 1913, James F. Morgan had just been released and went to an IWW rally in downtown Salt Lake City. Rallygoers first sang "Mr. Block," a popular song written by Hill.

As Morgan began to speak, a man who had helped arrest Wobblies in Spanish Fork Canyon led an attack on the crowd. An IWW member pulled out a pistol and started shooting, and a riot broke out.

The attackers were hailed as heroes in the next day's newspapers, and Wobbly popularity in the Mormon capital reached a new low.

That's about the time Hill arrived, along with a friend named Otto Appelquist.

Hill and Appelquist stayed on and off with John and Ed Eselius in Murray, Utah. The Eselius brothers had met Hill and Appelquist as the four men, all Swedish immigrants, worked in San Pedro.

Murray had an impoverished but tight-knit Swedish community, and Hill was a welcome addition. Roger Tonnesen, 82, remembers hearing his mother talk about her brothers' friendship with the songwriter.

"We'd have parties at our house," she told him, "and Joe Hill would come over and bring his guitar and they'd all sing songs and have a good time."

Hill worked for a short time at Park City's Silver King Mine, which belonged to former U.S. Sen. and Salt Lake Tribune owner Thomas Kearns. He fell ill near the end of 1913 and spent two weeks in the Miners Hospital in Park City. Appelquist found work as a steelworker on the Eccles building in Ogden.

Tonnesen's grandfather Olaf Lindegren remembered meeting Appelquist at a Christmas party in 1913. Appelquist was introduced as the fiancé of a woman who was a cousin of the Eselius brothers, Lindegren later wrote. Her name was Hilda Erickson.

Eselius house

The home of the Eselius brothers in Murray, Utah, where Joe Hill was arrested on Jan. 14, 1914, for the murders of John G. and Arling Morrison. Photo courtesy Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

‘Nobody's business'

Someone shot Hill in the chest on Jan. 10, 1914.

"Where or why I got that wound," he would insist, "is nobody's business but my own." Around 11:30 that night, he arrived at the home office of physician Frank McHugh in Murray. He told the doctor he had been shot by a friend in a quarrel over a woman and asked the doctor to keep it quiet.

A gun in a shoulder holster fell from Hill's clothing during his care.

Another doctor, Arthur Bird, had stopped by after seeing McHugh's light was still on. Bird drove Hill back to the Eselius house around 1 a.m. Sunday.

Appelquist and Hill spoke privately in a separate room while the Eselius family readied a cot for Hill. Appelquist then announced that he was going to look for work and left.

Police searches for Appelquist days later were fruitless, and there are scant records about the rest of his life.

Hill rested at the Eselius house until Tuesday evening, when police arrived to arrest him.

A grocer named John G. Morrison and his teenage son Arling had been killed the same night Hill was wounded. Two masked men had entered the family's Salt Lake City store just before 10 p.m. and shot them.

But Arling, the police believed, had shot one of the intruders before he died. One or both of the doctors who saw Hill that night had tipped police.

Hill was booked into the Salt Lake City jail. Early on Wednesday, Jan. 14, 13-year-old Merlin Morrison approached his cell.

The boy, who had been working in the store with his father and brother, told police and reporters that Hill was about the same build as one of the killers he saw.

↕ Investigating Joe Hill

It wasn't long before the police figured out that Hill was a Wobbly. And not just any Wobbly, either. This was the guy who wrote the song they were singing downtown before everything went crazy last August. This guy was a big deal to the IWW.

Hill decided to represent himself during the January preliminary hearing and he was bound over for a trial that would take place in June.

Judge M.L. Ritchie presided over the trial and Hill was no longer defending himself. He had two attorneys, Earnest D. MacDougall and Frank B. Scott.

On the first day of the trial, Merlin Morrison took the stand. The Salt Lake Tribune reported that if Hill were to be convicted, it would be based on the strength of the boys testimony. The young Morrison "declared positively" that Hill's "general build, height, form of body and shape of head" was like one that of one of the two men who had killed his father and brother.

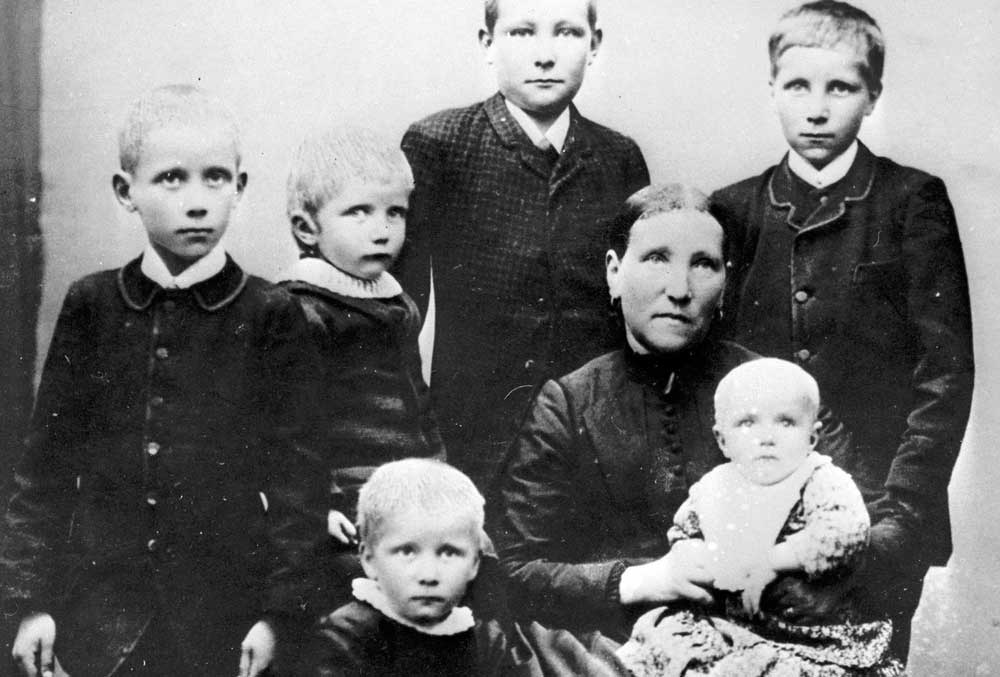

The Morrisons

Left to right, John G. Morrison, Arling Morrison, Merlin Morrison were working in their grocery store the night of Jan. 10, 1914. John and Arling were both killed by masked men.

Guilty as charged

Critics of Hill's conviction and execution typically raise these issues: He had no motive, the prosecution was based nearly solely on the fact he was shot that same night, there was no reliable identification of him as one of the killers, and his attorneys were incompetent.

Yet Hill remains an enigma for never disclosing details of his alibi when the information probably would have saved his life.

↕ Why stay silent?

Why didn't Joe Hill save himself? Read the story here

Hill represented himself during his January preliminary hearing and was ordered to stand trial. On the third day of his June 1914 trial, his frustration with his lawyers — Ernest D. MacDougall and Frank B. Scott — escalated, and he tried to fire them. "Sensation after sensation piled up yesterday in the Joseph Hillstrom murder trial," The Tribune reported. "Hillstrom discharged his own attorneys, F.B. Scott and E.D. McDougall [sic] in open court, declaring that they were in league with the district attorney and that he could conduct his own defense better than they."

Judge Morris L. Ritchie allowed the jury to remain as he initially questioned Hill, then resumed testimony over Hill's continued objections. In the end, after a recess, Hill agreed that Scott and MacDougall could stay on.

Another "sensation" came when two women entered the courtroom that day, "each shrouded in mystery, which counsel for the defense could not or would not clear up," The Tribune said.

One was Erickson, Appelquist's former fiancé. Many speculated she was the woman behind Hill's shooting. But when asked by reporters, his attorneys said they did not know who Erickson was, and they complained that when they asked Hill about her, he "shuts up like a clam."

The other woman was Virginia Snow Stephen, the daughter of late LDS Church President Lorenzo Snow. She was an art professor at the University of Utah and prominent in Salt Lake City's social circles. She was convinced Hill was innocent.

Stephen contacted well-known labor attorney Judge Orrin N. Hilton of Denver, who had been representing union members in high-profile cases for years. He wasn't able to join Hill's team immediately, but he recruited a local attorney, Soren X. Christensen, to sit in on the trial. Hilton also agreed to handle an appeal, if one was needed.

Hill was convicted of first-degree murder on June 27, 1914. At his July 8 sentencing, he chose the firing squad.

Virginia Snow Stephen and Hilda Erickson

Both women attended Joe Hill's trial shrouded in mystery.

‘I am going now'

Goodbye, Bill, I die like a true blue rebel. Don't waste any time mourning. Organize.

Hill had become international news. The IWW started a letter-writing campaign in an effort to free him. Letters came in from around the globe, and there were rallies and protests around the country.

Union halls drafted resolutions and sent petitions. Utah Gov. William Spry heard from people opposed to the death penalty, as well as some who threatened to kill Spry if Hill wasn't released and a few who complimented the governor on the handling of the case.

Hill was prolific as well, writing articles and songs that appeared in various Wobbly publications. They include the song "Rebel Girl," inspired by his friendship with IWW leader Elizabeth Gurley-Flynn, and a later telegram to IWW leader William Haywood that would become a mantra for his supporters.

"Goodbye, Bill, I die like a true blue rebel," he wrote shortly before the execution. "Don't waste any time mourning. Organize."

Hill's appeal to the Utah Supreme Court failed; the justices ruled against him on July 3, 1915.

Hilton's plea for a commutation of Hill's sentence from the Utah Board of Pardons failed; the board ruled against him on Sept. 18, 1915.

With hours to go before Hill's scheduled Oct. 1 execution, President Woodrow Wilson sent a telegram to Spry, asking for a postponement so the Swedish minister could have time to examine the case.

Spry reluctantly agreed. But when the stay expired shortly after Hill's 36th birthday, he rebuffed Wilson's second request, and Hill's execution by firing squad was set for Nov. 19, 1915.

The Salt Lake Herald-Republican declared in bold red type: "Governor turns deaf ear to Wilson's appeal; Hillstrom to be shot to death this morning."

The Salt Lake Telegram's headline read: "I.W.W.'s must leave Utah, says Spry."

When Hill was led into the prison yard blindfolded, he seemed to be calling out to the friends he had asked to attend. The warden had refused to let them in.

"I am going now, boys," Hill said. But no one answered.

The guards strapped him into a chair. The Herald-Republican reported his last words: "Let it go, fire."

Joe Hill House mural

This mural depicting the execution of Joe Hill was on one of the walls inside the Joe Hill Hospitality House, a homeless shelter in Salt Lake City run by a social activist named Ammon Hennacy in the 1960s and '70s. Photo courtesy Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

jharmon@sltrib.com Joe Hill on Instagram

Join the discussion

Join the discussion