The Morrisons and the Hägglunds meet

A family finds peace

Lovisa Samuelsson took the stage around noon. With a guitar that once belonged to folk singer Utah Phillips, she began a song she had written about her great-great-uncle Joe Hill.

"Goodbye, Joe," she sang quietly.

Samuelsson's mother, Pia, and her uncle, Rolf Hägglund, stood with her, counting backward from 60 to represent the final minute of Hill's life — spent strapped to a chair, a target pinned to his chest, before a Utah firing squad.

Their September performance in Sugar House Park brought a little bit of Hill — literally — back to the site of the execution, in a homecoming nearly 100 years later.

After his controversial conviction for the murder of Salt Lake City grocer John G. Morrison, the labor songwriter was sentenced to die on Nov. 19, 1915. He asked his friends to take his body over the state line, famously quipping that he didn't want to be caught dead in Utah.

Hill was cremated in Chicago, his ashes sent to friends and sympathizers around the country. Some found their way into Phillips' guitar.

So there they were, at the former site of Utah's prison: Hill's relatives, who had traveled from Sweden, and Joe himself.

John Morrison's descendants had been dreading centennial events like this. The loss of John and the teenage son killed with him left the Morrison family with lingering pain and anger, amplified by the enduring legend of Joe Hill.

But the past year, as they've told their story and had an extraordinary meeting with Hill's relatives, has transformed them.

It finally gave me a new perspective. A fresh breath. That I'm not going to think the same way I have in the past. I'm going to let it go.

Marilyn Morrison-Ryan, John Morrison's granddaughter, spent hours at the daylong commemoration for Hill on Labor Day weekend. As she listened to Samuelsson sing, she said she felt empathy for the Swedish family.

"It finally gave me a new perspective. A fresh breath," Marilyn said. "That I'm not going to think the same way I have in the past. I'm going to let it go."

And now, with the anniversary coming Thursday, she feels a peace that seemed out of reach just last spring.

"If we hadn't met the Hägglunds," she said, "we would still be carrying that cross that we chose to carry."

Hill's great grandniece meets Morrison's granddaughter

Lovisa Samuelsson, the great grandniece of Joe Hill, meets Marilyn Morrison backstage during the Joe Hill Centennial Celebration in Sugar House Park on Sept. 5, 2015. Morrison is the granddaughter of John G. Morrison, the man Hill was convicted of killing in 1914. The concert was organized by the Joe Hill Organizing Committee as a way to honor the life and legacy of the labor icon who was executed nearly 100 years ago on November 19, 1915. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

In Hill's shadow

The Morrisons were suspicious when reporter Tom Harvey and I asked them to share their history in March.

We expected to meet Jay Morrison, John Morrison's great-grandson, at his home in Highland. We hoped he would have family stories and perhaps old photos to share.

But when we arrived, we were met by a small crowd. Generations who had splintered over time were united in their concern that we were poking around the sorrow they wanted to forget.

They spoke of their family's unusual place in Hill's shadow, feeling forgotten as he is remembered as a martyr for labor and an influential musician. They talked about how writers and historians have gotten basic facts about their family wrong.

For them, this story isn't about history or Hill's legacy — it's a tragedy that still has the power to draw tears.

John Morrison and his son Arling, 17, were killed on Jan. 10, 1914, by two masked gunmen who burst into the family's small grocery store at 778 S. West Temple and yelled, "We've got you now!" Younger son Merlin Morrison, 13, was in the back of the shop.

The murders thrust the family into the spotlight, into financial hardship and into Hill's domain, where the radical Industrial Workers of the World union he'd joined was in a class war against the one-percenters of the day. No eyewitnesses definitively identified Hill, no one testified that he had known John Morrison and, since the gunmen immediately fled without attempting a robbery, Hill's alleged motive was unclear. For many, John Morrison's death became known as the excuse Utah used to weaken the IWW.

But the Morrisons grew up hearing Merlin's account of the night and his unshakable conviction that Hill was guilty. The key evidence against Hill was the gunshot wound for which he was treated the night of the murders, which he told police he'd received in a fight with a friend over a woman. He refused to say more, and police theorized Arling had been able to return fire and struck Hill before dying. The family celebrated Arling as a hero.

In November 1915, John Morrison's widow, Marie, briefly told a reporter that she was happy with how Gov. William Spry had handled Hill's sentence. What wasn't reported: the death threat against the family that followed.

The Morrisons have an audio recording made in the 1960s as Marie discussed the threat with her son Robert.

"About a couple of days later," she said, "why, that little piece that was in the paper was cut out and on the top of it, on the same part of the paper, it said, it was printed, ‘You, Y-O-U, have signed Perry's death warrant.'?"

Perry was Marie's oldest living child. Her fear shaped how she lived and raised her children; her grandchildren still recall how she had her windows painted shut to help her feel safe.

"Each year that the events [honoring Hill] would come up it would raise those emotions again of disappointment, anger and some fear," Marilyn said.

At a gathering in April, 85-year-old John Arling Morrison, a grandson of John Morrison, grumbled, "Here's Joe Hill, rearing his ugly head again."

But our questions sparked conversations between relatives who hadn't spoken to one another in years. Their views of the past shifted as they shared sometimes-differing family stories. Hearing about our reporting helped them understand where those stories do, and don't, fit with court documents and other records.

And while they still believe Hill was guilty, they've been touched to learn how many people feel empathy for their family.

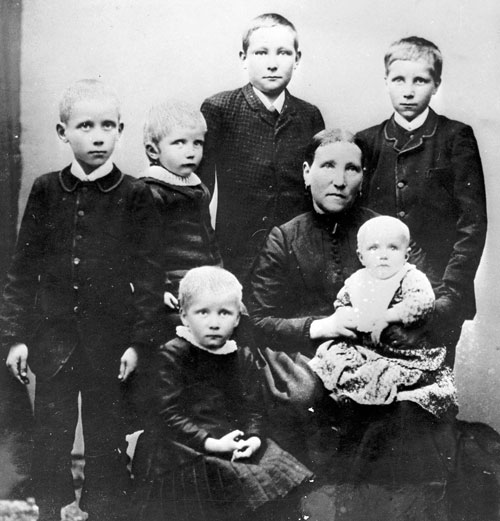

John G. Morrison's family meets Joe Hill's family

In 1914, Joe Hill was convicted of killing John G. Morrison. Hill was executed for the crime on Nov. 19, 1915, an act that remains controversial today.

Instant bond

When I told Jay that Hill's relatives were coming to Salt Lake City for the September concert, he asked if I could arrange a meeting. At first, Jay and Marilyn thought they would keep the idea quiet, concerned about other relatives' past hostility. But soon, the extended Morrison clan was eager to come. I was nervous, hoping the gathering would be a positive experience for both families.

That evening, the night before the September concert, their bond seemed instant.

Marilyn and Rolf Hägglund, the grandson of Hill's brother, clasped hands and held tight the moment they met at Marilyn's condo near Hogle Zoo.

Eighty-year-old Merlin Morrison — named for his father, the 13-year-old witness who testified against Hill in 1914 — beamed as he shook hands with Rolf, Rolf's sister Pia and his wife, Annya.

"It's amazing that we're all here and we all understand," Merlin said. "There is no animosity. We all wish that what happened didn't happen, but it did, and it's in the past."

Both sides had been worried about meeting. At first, Pia said, "I really wondered what I was doing there." She was afraid she would be forced to defend her family's belief that Hill was wrongfully executed.

"Oh, how wrong I was," she said.

The Tribune's first story about the impact of the murders on the Morrison family was published a week before the families met. Leslie Clements, Marilyn's daughter, said, "The thing that was most surprising to me when this whole thing started was that there was going to be a voice for our family."

It's been important to share their history not only with the public, but with each other, she added.

"I think some of the progression was really getting back into the genealogy of our family," Leslie said. "It's a sad story, on both sides, but for me it's nice to see my family members just take a deep breath and say this is some kind of peace that we can find so we don't have as much anger and anxiety about this anymore."

Jay said, "We've been working it like we're trying to forget it. And now we can keep it as a memory because it doesn't have to be painful."

John Arling, who is Jay's father, said he had always wished people would just forget about Joe Hill, so the reminders of his family's trauma would stop. The meeting, he said, gave him the same realization; he can remember his family's history but let go of their pain.

Two families meet

Pia Samuelsson shakes hands with John Arling Morrison during an event where the two families met each other on Sept. 4, 2015. Samuelsson's and Hägglund's grandfather was Joe Hill's brother. The other two men standing by them are Rolf Hägglund, Samuelsson's brother, and Merlin Morrison, John Arling's cousin. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

'Put the old stuff behind'

Rolf said that before the meeting, he hadn't understood the burden the Morrisons have carried through the years. He had only ever considered the events from his family's point of view.

"During our get-together I felt real warmth and love and some kind of longing to put the old stuff behind," he said recently in an email.

At the September concert, Rolf was scheduled to speak for 5 minutes about Hill. But when one performer didn't show, Rolf was given an extra 10 minutes. He used the time to speak about the Morrisons.

During our get-together I felt real warmth and love and some kind of longing to put the old stuff behind.

He said that to his family, Hill had disappeared when he left home and immigrated to America.

"He was lost in this continent," he said. But when John and Arling Morrison were shot, the Morrison family lost a father, a provider, a brother and a son.

"That's a bigger loss than the loss we had, so my heart goes out to the Morrison family," Rolf said.

After he left the stage and walked back to where the two families were sitting together in the grass, Leslie and Marilyn embraced him with tears in their eyes. The families have continued their conversations by email.

"Since Joe didn't leave any family of his own in the U.S.," Rolf wrote recently, "maybe I could adopt the Morrisons as the U.S. branch of the Hägglunds."

Joe Hill Centennial Celebration

Merlin Morrison, left, Marilyn Morrison-Ryan and her daughter Leslie Clements watch the Joe Hill Centennial Celebration in Sugar House Park on Sept. 5, 2015. The concert was organized by the Joe Hill Organizing Committee as a way to honor the life and legacy of the labor icon who was executed nearly 100 years ago on November 19, 1915. The Morrison family are descendants of John G. Morrison, the man Hill was convicted of killing in 1914. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

jharmon@sltrib.com @JoeHill_history

Join the discussion

Join the discussion