Joe Hill's music

The defiant power of song

Mr. Block knew he could rely on his employer to take care of him and his family.

He could count on his political leaders, too. And if for some reason they failed, there was still the law to protect him. He was a common worker, proud to be a believer in the system.

The Wobblies couldn't believe how naive he was.

"Tie a rock on your block," the radical union members sang fiercely, at meetings, at street rallies, on picket lines. "And then jump in the lake, kindly do that for Liberty's sake!"

The scornful "Mr. Block" lyrics were written by Joe Hill, a Swedish immigrant who worked as a laborer around the West and became a famed songwriter for the Industrial Workers of the World, known as the Wobblies.

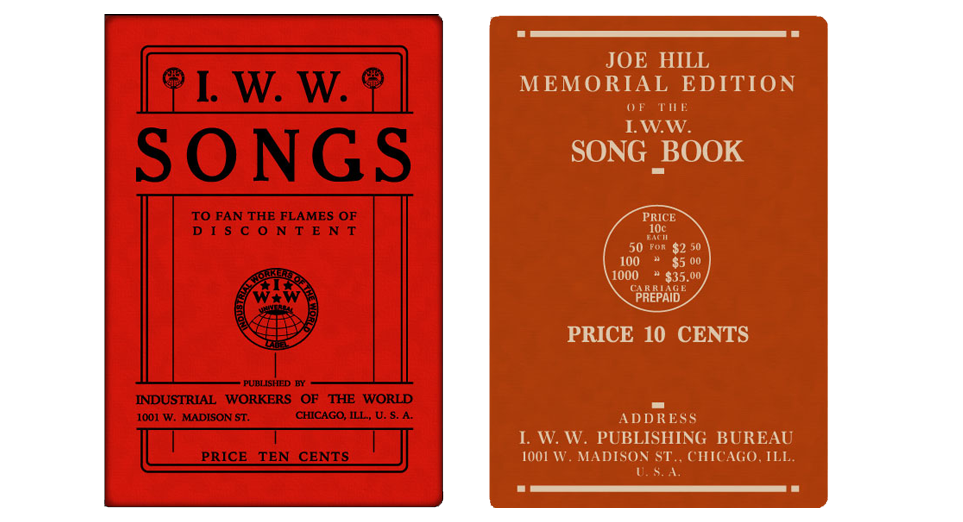

The union's "songs to fan the flames of discontent," published in its iconic Little Red Songbook, empowered workers from cultures around the globe, giving them a defiant unified voice for protest, for fellowship and for propaganda.

"What first attracted me to the IWW," wrote early union musician Richard Brazier, "was its songs and the gusto with which its members sang them."

Hill's songs were simple and pointed, aimed at exposing injustice and forcing exploited workers to, in the language of today's Black Lives Matter movement, "stay woke." An IWW rally in Salt Lake City on Aug. 12, 1913, began with about 500 people singing "Mr. Block" at 100 South and Regent Street, across the street from what is now the Cheesecake Factory at City Creek Mall. It ended in a riot; several people were shot after security guards for Utah Copper attacked an IWW speaker.

The next day, IWW strikers were singing "Mr. Block" in the hop fields of California's Durst Ranch. When law enforcement arrived, two workers and two county officials were killed in the confrontation.

The inciting power of Hill's writing is what made his songs significant, said American folk singer John McCutcheon, who recently recorded an album of Hill's IWW songs.

"'American Idol' is a lot of people's entree to what it means to be a musician," McCutcheon said. "It's so antithetical to what Hill's life and work was all about that I think it makes him all the more important."

Little red songbook

Left, illustration of the Industrial Workers of the World's songbook from 1915. Right, illustration of the Joe Hill Memorial edition of the IWW songbook.

Singing 'cold, common sense'

"A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over.

Hill came to Utah in 1913 and worked briefly in the Silver King Mine in Park City. In January 1914, he was arrested in the murder of a Salt Lake City grocer and the store owner's teenage son, a crime many — then and now — do not believe he committed.

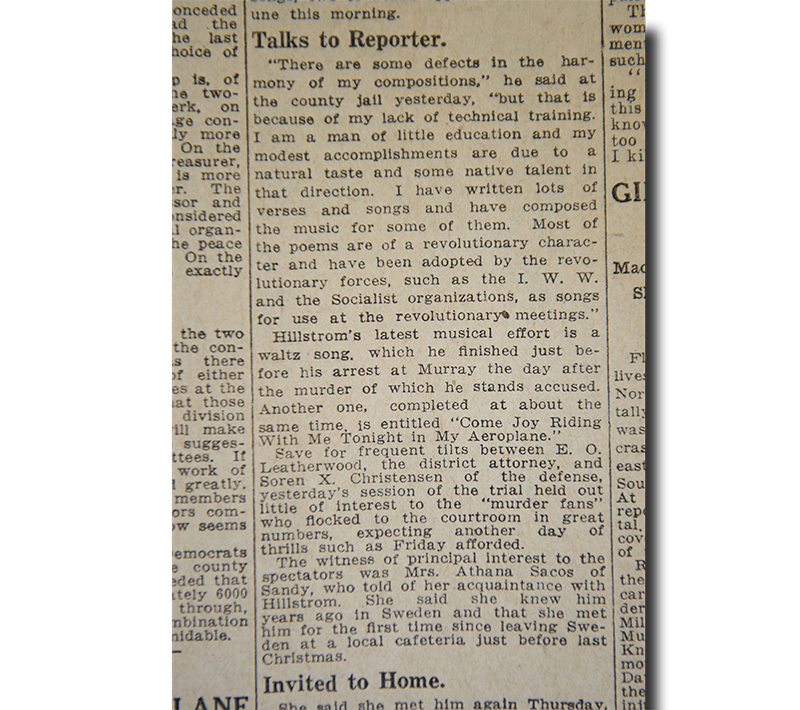

On June 21, 1914, while Hill was on trial, The Salt Lake Tribune published a brief jailhouse interview with him about his songwriting.

"There are many defects in the harmony of my compositions, but that is because of my lack of technical training," he said. "I am a man of little education and my modest accomplishments are due to a natural taste and some native talent in that direction."

He saw music as a powerful way to enlighten workers, he told the editor of Solidarity, an IWW newspaper, five months later.

"A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once," he wrote. "But a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over."

"If a person can put a few cold, common sense facts into a song and dress them — up in a cloak of humor to take the dryness off of them, he will succeed in reaching a great number of workers who are too unintelligent or too indifferent to read a pamphlet or an editorial in economic science."

Among Hill's most enduring songs: his biting "The Preacher and the Slave," a parody of the hymn "In the Sweet Bye and Bye." He coined the phrase "pie in the sky" for his chorus, describing churches who hound workers for donations, ignore hungry families and preach:

You will eat, bye and bye,

In that glorious land above the sky;

Work and pray, live on hay,

You'll get pie in the sky when you die.

The Preacher and the Slave

"The Preacher and the Slave" is arguably Joe Hill's best-known song. It parodies the popular Salvation Army hymn "In the Sweet Bye and Bye." The song is performed by Andrew Shaw outside the historic City and County Building in Salt Lake City, Utah, where Hill was tried and convicted in the murder of John G. Morrison.

His organizing anthem, "There is Power in a Union," rewrites "There Is Power in the Blood (Of the Lamb)." The hymn begins, "Would you be free from the burden of sin?"

Hill has a different question, and his own solution.

Would you have freedom from wage slavery,

Then join in the grand Industrial band;

Would you from mis'ry and hunger be free,

Then come! Do your share, like a man.

When sung today, listeners are urged to "Do your share, lend a hand."

There Is Power in a Union

"There Is Power in a Union" is one of Joe Hill's most enduring recruiting songs. After his execution, the song was sung at his funeral in Salt Lake City and again at his funeral in Chicago. The song is performed here by Folk Hogan in Salt Lake City's Sugar House Park, near the site where Utah's state prison once stood and where Hill was executed by a firing squad on Nov. 19, 1915.

Organizing through music

Hill often set his songs to the tunes of popular hymns, a strategy as practical as it was subversive. Workers and passersby at rallies knew the melodies and could quickly learn the new words, perhaps paying a few cents for a copy of the red songbook.

The tactic also thwarted opponents who tried to disrupt IWW gatherings. The Salvation Army would famously send its brass bands to drown out speeches by IWW firebrands — a plan defeated when a crowd could fill in the rebel lyrics.

"It meant that the bands that the bosses were sending out were kind of like performing for the workers and adding to the whole event," said English artist Billy Bragg, one of the musicians on the 1990 album "Don't Mourn — Organize: Songs of Labor Songwriter Joe Hill."

Hill was writing songs for a purpose, said Utahn Lori Taylor, a historian who produced "Don't Mourn — Organize" for the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings label.

↕ Joe Hill speaks with The Salt Lake Tribune about his songwriting

Interview with The Salt Lake Tribune

In this interview published on June 21, 1914, Joe Hill talks to The Salt Lake Tribune about his songwriting. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

"They wanted to get attention on the street corner," Taylor said. "The way to capture attention was through music. So, you capture the attention and then you can talk to them. And then you can organize them. You can make them aware of how they're being manipulated."

McCutcheon describes Hill as a "utilitarian songwriter" who "wasn't writing songs for the ages. He was writing songs to be useful."

The key, McCutcheon said, was that while union organizers were motivated by their ideology, Hill's lyrics spoke directly to workers.

"They didn't have to be told an ideology to connect the dots. They just knew that their families were starving," McCutcheon said.

The legacy of Joe Hill's music

In 1990, historian Lori Taylor produced an album titled "Don't Mourn — Organize! Songs of Labor Songwriter Joe Hill." She discusses Hill's musical lineage and the power of music to prompt social change.

The Songs of Joe Hill

"The Songs of Joe Hill" by folksinger Joe Glazer was released in 1954 on Folkways Records. It is the first full album of Joe Hill's material. In addition to 9 songs written by Hill, the album also includes the 1930 Alfred Hayes song "I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night" and a reading of Joe Hill's Last Will, the poem Hill wrote on the eve of his execution. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

Songs of solidarity

Hill was writing during a politically volatile time, when millions of immigrants lured to the United States by fabled "streets of gold" instead found a meager existence working in sweatshops and in mines, on ranches and on railroads.

McCutcheon believes Hill's songs raised awareness of social inequality much in the same way the Occupy Wall Street protests trumpeted current economic disparities.

"These songs are a hundred-year-old version of what is happening today," he said.

"In a lot of ways, Joe was not an organizer. He was more of an agitator, which is really different," he said. "Occupy was about agitation. The step that needed to come after Occupy was 'OK, what do we do about this now?'"

Hill and folk singers who followed him also were reporting on social conditions through music, Taylor said.

"I think the history of folk song in America is the unedited story of ordinary working people," Bragg agrees, "and Joe made a big contribution in writing that story through the songs that he wrote."

Hill's techniques and the "usefulness" of his lyrics made his songs a template for later American folk music, McCutcheon said. His influence can be traced through Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie to Bob Dylan to Bruce Springsteen to Bragg and the rock group Rage Against the Machine.

Like the IWW, the American civil-rights movement took advantage of the power of music, McCutcheon said.

"Even the most connected people can usually only name two [speeches]" from the era. But with songs, he said, "I have to stop people at 10 or 12. What does this tell you? It's the songs that conjure up a sense of community and solidarity."

Civil-rights activists used black spirituals like "This Little Light of Mine" and "Go Tell It on the Mountain" in a way that gave them new meaning, much as Hill had rewritten hymns.

"We Shall Overcome" was sung by protesters across the country. Artists across genres advanced the theme of civil rights, including Billie Holiday's "Strange Fruit," Peter, Paul and Mary's "If I Had a Hammer," The Byrds' "Turn Turn Turn," Dion's "Abraham, Martin and John," Guthrie's "This Land Is Your Land" and scores more.

Hill's own story also continues to inspire musicians. "Joe Hill," with its opening line, "I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night," has been sung by artists since it was written in the 1930s. Joan Baez, for one, sang it at Woodstock. She sang it years later in Sugar House Park, the former state prison grounds where Hill was imprisoned and executed. She sang it in 2011 at an Occupy Wall Street rally on Veterans Day.

Joe Hill's funeral

The Salt Lake Herald-Republican reported on plans for Joe Hill's funeral on the day of the Nov. 21, 1915, service. As expected, mourners sang 'There is Power in a Union' as they escorted his Hill's body to a train depot. The body was sent to Chicago for a larger funeral there. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

'We could win victories again'

Bragg wrote his own version of "There Is Power in a Union" after hearing Hill's music during his first American tour in 1984. The trip coincided with a coal miners strike in the United Kingdom, a conflict Bragg described as an "epochal class struggle" between Britain's National Union of Mineworkers and Margaret Thatcher's government.

Bragg's version is based on the melody of a Civil War-era song called "Rally Around the Flag." It was released on his 1986 album, "Talking With the Taxman About Poetry," which cracked the Top 10 in U.K. album charts.

The longevity of older union songs gives them a unique power, he said.

"Perhaps there might be some people tomorrow who are coming to a strike or demonstration for the first time. When they hear these songs that are a hundred years old, they'll understand that they're not the first people who have fought these fights," Bragg said.

"We've managed to get things like the eight-hour day. We've managed to get things like paid leave.

"To know that others have fought these fights allows you to draw a strength from that. The victories that have gone before give you the sense that we could win victories again."

Join the discussion jharmon@sltrib.com Joe Hill on Instagram

Join the discussion jharmon@sltrib.com Joe Hill on Instagram