Masked men hold up Salt Lake City grocer

A look at the night a father and son were murdered in their Salt Lake City grocery store — and someone shot Joe Hill in the chest.

It was a cold Saturday night in Salt Lake City and 13-year-old Merlin Morrison was spending it working at his family's grocery store.

The last customer had left, and Merlin was in the back of the store at 778 S. West Temple, which stood just north of the intersection with 800 South. His older brother Arling, a kind 17-year-old known in the family for his affection for his younger siblings, was sweeping up behind a counter. His father, John, was moving a bag of potatoes near the front door.

They would restock the shelves for Monday, but with no refrigeration, they planned to take the fresh fruits and vegetables to their nearby home for the rest of the weekend.

It was just past 9:45 p.m. on Jan. 10, 1914.

Outside the store, Frank and Phoebe Seeley were walking home along 800 South after seeing a vaudeville show at the Empress Theater.

Around 9:35 p.m., they were surprised when two unyielding men, one taller than the other, forced them off the sidewalk. Phoebe Seeley's description of the men changed over time; at trial, she said one of the men had a distinctive scar on his face and neck and was wearing a red bandana around his neck.

The men were walking east toward the Morrisons' store.

Working in the store

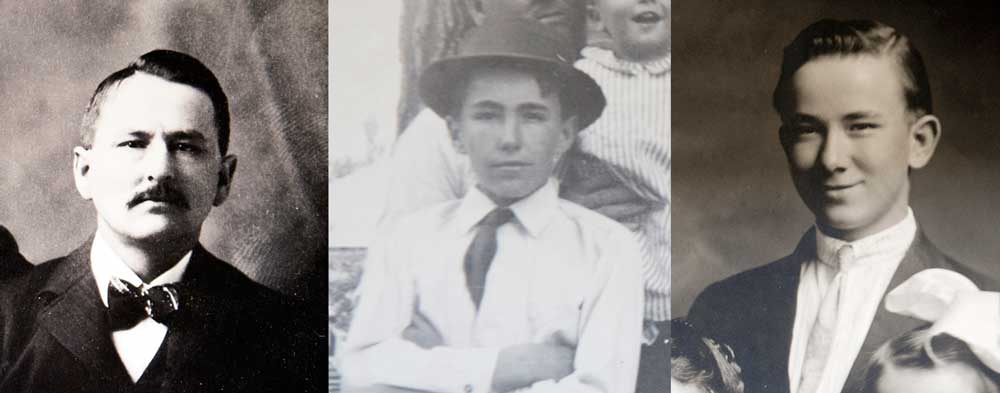

Left to right, John G. Morrison, Arling Morrison, Merlin Morrison.

Ten minutes later, two men with red bandanas over their noses and chins burst into the store.

"We've got you now!" one cried, and immediately shot John Morrison.

Merlin's accounts of what he could see varied, from his statements to police and reporters after the shooting to court proceedings to memories he shared years later with his children. Initially, he said he saw the taller man shoot his father, and saw his father fall.

↕ Court proceedings

Was Joe Hill's trial "legal but unfair," as his appellate attorney contended? Read about the evidence here.

Arling grabbed his father's Colt .38 from its hiding place in an ice chest. Prosecutors contended he fired and struck one of the assailants before he was shot three times and fell dead.

The killers made no attempt to take any money before fleeing.

Merlin ran to his father, then to Arling, before calling police.

The store

This is an interior view of John G. Morrison's grocery store at 778 S. West Temple. John G. Morrison was fatally shot on Jan. 10, 1914. Photo courtesy of the Morrison family.

In the next few minutes, several neighbors who heard the shots moved to their windows or went outside. All described seeing men heading south away from the store, crossing 800 South and going into an alley between 800 and 900 South.

There's debate over whether Arling had successfully fired and hit an intruder — the only blood police found in the store was from the slain Morrisons, and no blood was found directly outside the door. However, blood trails farther away were discovered the next day, including drops along the alley.

The neighborhood witnesses said one fleeing man moved more slowly than the other and clutched his chest. Vera Hansen, who had stepped outside, believed she heard a man say, "Oh, Bob." From inside her home next to the alley, Nellie Mahan heard a man say, "I'm shot"; some accounts say she also heard him call out the name Bob.

The murders had occurred just before 10 p.m. Around 11:25 p.m., several blocks west — near the corner of 800 South and 800 West — Peter Rhengreen saw two men part ways on the sidewalk.

The taller man walked toward Rhengreen, then suddenly lay down or collapsed, shut his eyes and began moaning. But he then got up and briefly followed Rhengreen before boarding a passing streetcar.

Streetcar conductor J.R. Usher said he saw a man board his car around 11:26 p.m. at 800 West. The man sat hunched and had appeared to be drunk when he boarded, but not when he got off at Main Street, Usher said.

That night, Joe Hill — with a gunshot wound in his chest — appeared at the home office of physician Frank M. McHugh.

↕ Who was Joe Hill?

Joe Hill was a famous songwriter for the radical union Industrial Workers of the World. Read more here about how his music still resonates and inspires today.

Read more about Joe Hill's life

At trial, prosecutors later wrote, McHugh testified that Hill arrived between 11:30 p.m. and midnight.

McHugh's office was at 1400 South and State Street in Murray, or 104 S. State St. by Murray's street grid. But the valley's grid has since been adjusted — so what was 1400 South then is 3300 South today.

Hill, a laborer who had worked around the West after immigrating from Sweden, told McHugh he was shot in a tussle with another man over a woman. He asked the doctor to keep it quiet.

Hill had been shot from the front, and the bullet passed through his lung before exiting out his back, the doctor testified.

At one point, a gun in a shoulder holster dropped from Hill's clothing. McHugh said he handed it back to Hill without taking the gun from the holster and saw only the handle. Physician Arthur Bird, who had stopped by after seeing McHugh's light was still on, would later claim he had gotten a better look at the gun.

Hill's gun vanished. He later told a deputy he had tossed it out of Bird's car that night, as the physician drove him to the home in Murray where he was staying.

Hill and his friend, Otto Appelquist, had met two brothers from Utah while the four men — all Swedish immigrants — were working in San Pedro, Calif. The Eselius brothers later returned to Murray.

After Hill and Appelquist arrived in Utah in the fall of 1913, they stayed on and off in the Eselius home, in a neighborhood where Swedish immigrants predominated, many working in area smelters.

On Jan. 10, 1914, Hill and Appelquist spent the day at the Eselius house, working together on a broken motorcycle, the family later said. Hill left sometime after 6 p.m. According to a note found in Hill's pocket after his arrest, Appelquist had planned to spend the evening at the same theater the Seeleys had attended.

Appelquist's note said he was going with Hilda Erickson — a cousin of the Eselius brothers, who had recently broken off her engagement with Appelquist — and a woman who was a friend of Hilda's.

Bird and Hill arrived at the home around 1 a.m. on Jan. 11. Appelquist was there. He and Hill spoke in a separate room while the Eselius family readied a cot for Hill.

No one knows what Hill and Appelquist spoke about; an account in The Tribune speculated that Hill gave Appelquist the gun during their conversation.

But after Bird helped Hill get settled on the cot, Appelquist announced that he was leaving the house to find work — and vanished. Police searches were fruitless, and there are scant records about the rest of his life.

Love triangle?

Left to right, Joe Hill, Otto Appelquist and Hilda Erickson.

On Sunday afternoon, Erickson arrived at the Eselius home and talked with Hill, still on the cot and suffering. She remained silent about their conversation throughout Hill's trial, his supporters' pleas for new information, his appeal, his execution and for decades after that.

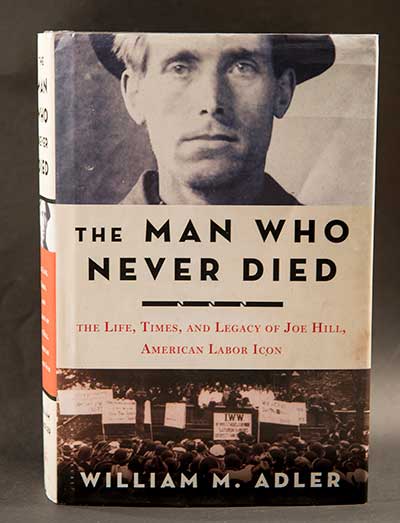

In his 2011 book, author William M. Adler wrote that he had uncovered a letter Erickson wrote in 1949 to a scholar researching Hill's case. "Otto shot him in a fit of anger," she wrote, and Appelquist was "sorry right after" and carried Hill to McHugh's office. "Then I knew that Otto went away because Joe may die."

She was "bewildered" when she heard about the Morrison murders, she wrote, but when she visited Hill in jail, he told her "not to say a word' because he was innocent and the state could not prove him guilty.

Others knew about the relationships between Hill, Erickson and Appelquist. As Hill's execution date neared, a friend of the Eselius family wrote to Utah Gov. William Spry and urged him to have Erickson questioned. It's unknown whether anyone followed up.

↕ The letter to the governor

Olaf Lindegren's daughter used hollyhock flowers as doll clothes as she played with friends in their impoverished Murray neighborhood of Swedish immigrants. Read more here about their lives and Lindegren's letter to the governor.

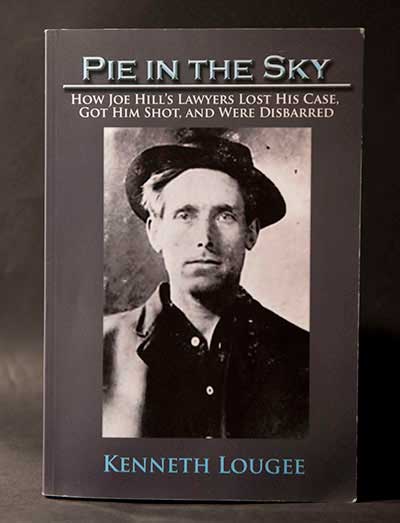

There are weaknesses to Erickson's story, Utah attorney Kenneth Lougee has written. And if true, it "implies callousness" by union officials who knew of Erickson's importance to Hill and by Erickson herself: "Why would Hilda let him go to a needless death?"

The investigation and prosecution would proceed without any testimony Erickson could have provided.

After learning of the Morrison murders, one or both of the doctors who had treated Hill tipped police to his gunshot wound.

Police quickly dropped their revenge theory — that a bandit thwarted by John Morrison in the past had returned to retaliate. John Morrison had twice fought off would-be robbers as a grocer, and in between those attacks, had briefly worked as a police officer.

Hill was arrested at the Eselius home late Tuesday, Jan. 13, 1914, and taken to jail.

Joe Hill on Instagram

Join the discussion about the trial

Join the discussion about the trial

Compiled and written by Sheila R. McCann and Jeremy Harmon