INDUSTRIAL Workers of the World

The power of 'One Big Union' comes to Utah

In America's Gilded Age, lavish mansions sprouted along Salt Lake City's South Temple street and landmark commercial buildings rose downtown.

Spectacular expansion in mining and railroads in Utah in the decades of economic growth before 1900 created huge gold, silver and lead fortunes and built up busy boom towns such as Alta, Ophir, Park City, Mercur and Tooele.

But the era also created a large and disaffected class of low-wage workers across the West, described by one historian as "womanless, voteless and jobless men" who drifted between harvest work, mining camps and other manual labor.

"They looked around and saw the immense wealth differential between themselves and the truly well-off," said Matthew Basso, an associate professor of history at the University of Utah. "There was a palpable sense that capitalism, even in democratic places like the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, was never going to be a just system for workers."

The Industrial Workers of the World — a revolutionary group by any definition — found rich potential for organizing workers in Utah's ramshackle mining and lumber camps, railroad yards and factories.

Known as Wobblies, IWW members would eventually count Utah among their Western hubs, opening local union chapters in Salt Lake City and maintaining headquarters in the Boyd Parker building at 170 S. Main St.

IWW members had first appeared in Utah at a 1910 convention of miners in Eureka. By the time famous Wobbly songwriter Joe Hill arrived in Utah in 1913, union members had played a role in at least three strikes in the state — among miners in Bingham Canyon, smelter workers in Murray and construction workers in the small town of Tucker.

Many in Utah's business community, church officials and elected leaders watched with rising tension, viewing the growing labor movement as a direct threat.

Duncan Phillips: Spreading the word

Duncan Phillips, the son of folk singer Utah Phillips, talks about the power of music, history and the media to educate people about what is happening in the world.

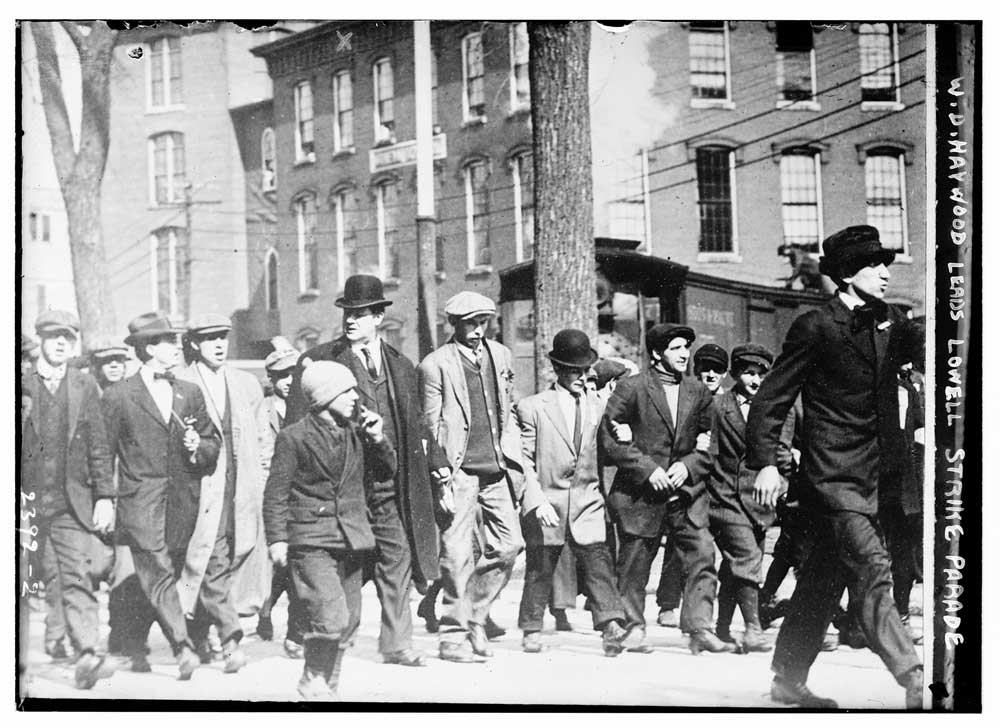

Big Bill

William "Big Bill" Haywood, born into poverty in Salt Lake City and a mine worker by age 9, was one of the IWW's founders. Launched in Chicago in 1905, the new industrial union inspired thousands of socialists, union organizers, anarchists and downtrodden workers nationwide.

A burly, one-eyed, plain-spoken firebrand who would live the last decade of his life in Communist Russia, Haywood did not shirk from the notion of class conflict. "The mine owners did not find the gold," he wrote in his 1929 autobiography. "They did not mine the gold, they did not mill the gold, but by some weird alchemy all the gold belonged to them!"

The mine owners did not find the gold, they did not mine the gold, they did not mill the gold, but by some weird alchemy all the gold belonged to them!

The IWW was based on the openly confrontational notion that "the working class and the employing class have nothing in common," as declared in the preamble to the group's constitution. It believed workers of every vocation and background had a historic mission to do away with "the slave bondage of capitalism," abolish the wage system and replace both with forms of self-management and workplace democracy.

While the IWW often organized in tandem with other labor unions, such as the Western Federation of Miners, IWW members held to their singularly revolutionary creed. Rejecting more traditional union activities based on worker-management cooperation, IWW members, particularly those based in the West, favored direct action to improve workers' lives, with tactics such as labor slowdowns, strikes and even sabotage.

Often faced with dangerous work conditions and below-subsistence pay, and commonly forced to live in squalid employer-owned housing, laborers were attracted to unions in large numbers. A 1975 history of U.S. labor estimated that nationwide union membership went from 868,500 in 1900 to more than 2 million within four years.

Wobbly numbers in Utah were never extremely large, but their influence was substantial, Basso said. "Virtually any worker in the fields where the Wobblies were active would have known about them and even known a Wobbly."

Big Bill

William "Big Bill" Haywood, a founder of the Industrial Workers of the World in 1905, is seen in a long coat and bowler hat as he led a strike parade in Lowell, Mass., in 1912. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

One Big Union

Despite the powerful influence of business interests and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Haywood and other Wobblies found Utah a notable foothold — in part due to its central place in the West's new railroad network and distinct features of the state's labor force.

With mine work discouraged by LDS Church leaders, the surge in demand for labor drew non-Mormon immigrants by the thousands to toil underground or in newly built mills and smelters.

The IWW was the lone U.S. union to welcome women, African Americans and, crucially, non-English-speaking immigrants. Although that alienated some white workers, Basso said, the big-tent approach appealed to many Greek, Italian, Finnish and Mexican immigrant workers in Utah's mining enclaves.

Haywood and other Wobblies also sought "One Big Union" open to all workers in all trades and crafts, whether skilled or unskilled. Many miners and lumber workers were unskilled menial laborers, excluding them from trade-centered unions of the time.

Economic forces and unsafe work conditions gave rise to other radical movements, as well.

The Socialist party, first organized in Utah in 1901, made significant gains around the same time as the Wobblies, particularly in mining communities. A decade later, 33 party members had been elected to public office in places such as Bingham, Fillmore, Cedar City, Salt Lake City and even the Utah Legislature.

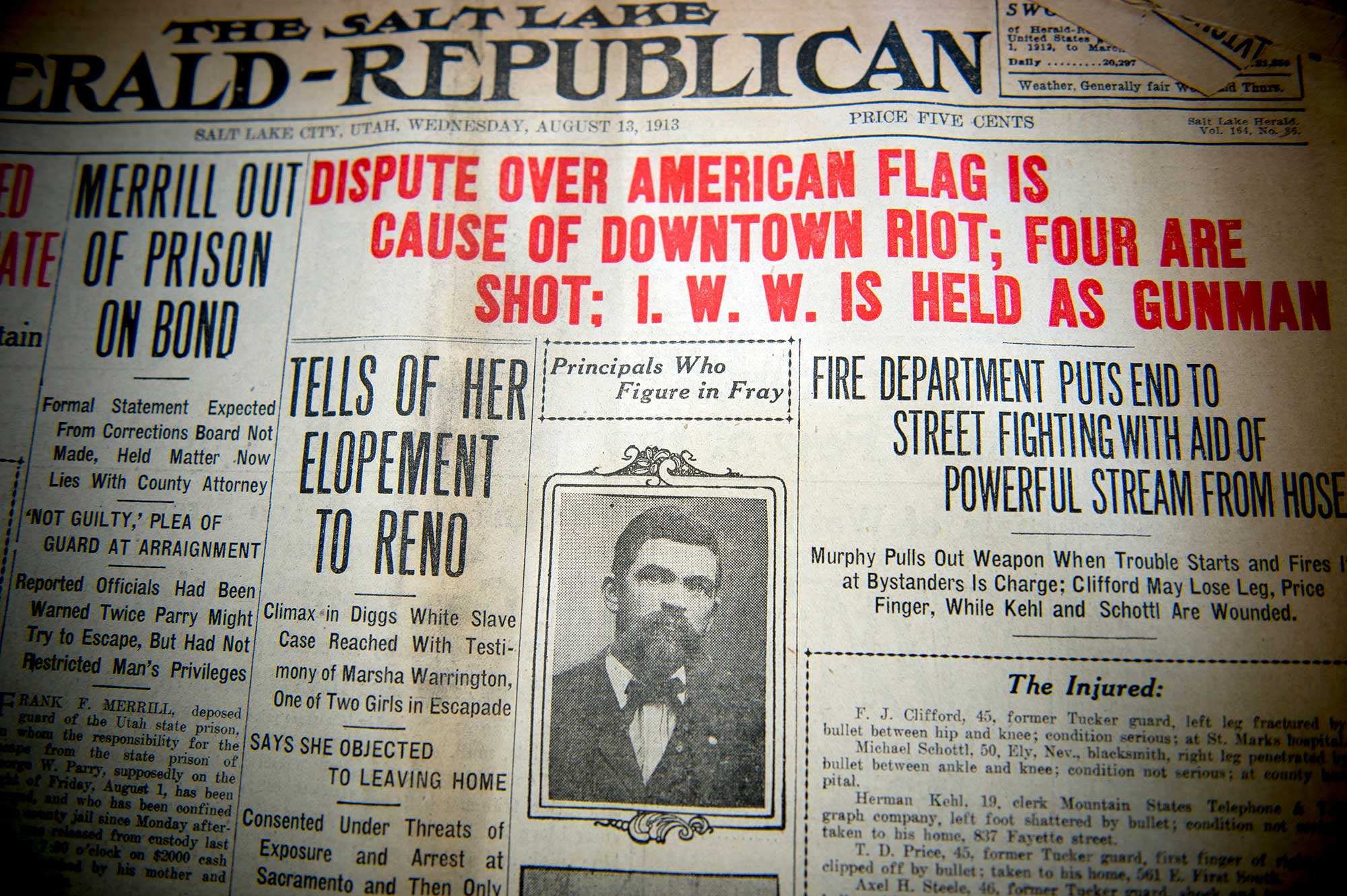

But as World War I broke out in Europe and Russia teetered toward a Communist revolution, Utah's political left and its national counterparts fell under increasing suspicion and law-enforcement crackdowns. Police officials and Salt Lake City's newspapers vilified its members, with special ire for IWW members.

"Riot, disorder, and contempt for law follow the entrance of their leaders into any community," the Salt Lake Herald-Republican wrote in 1913. "Discord covers their operations like a cloud of evil; every decent citizen regards them as his own and his country's enemies."

Virginia Snow Stephen

Virginia Snow Stephen, in the center of this unidentified group and wearing a cap, was a University of Utah art professor who believed in Joe Hill's innocence and worked to raise money for his defense. She is wearing an Industrial Workers of the World ribbon and one of the men on the floor is holding a program with a portrait of Hill on it. The program the other man on the floor is holding has the name of Oscar Larson's Swedish organization, Verdandi, on the cover. Photo courtesy Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah

Fighting for free speech

Both Socialists and Wobblies — as well as other groups — used outdoor meetings and street orators to gain members and spread their messages in a strategy known as "soapboxing." Radical gatherings in Salt Lake City and Ogden regularly drew large crowds, and in 1910, the Salt Lake City Police Department banned Socialist party meetings.

That ban would be followed in subsequent years by rules that forced radical groups to obtain police permits before gathering and a bar on them speaking anywhere downtown. One requirement limited their public events to Salt Lake City's red-light district.

Using another of their direct-action tactics, Wobblies regularly challenged these bans with what they called "free speech fights." IWW members would defy speaking bans en masse, clogging local jails and courts until restrictions were lifted. Free-speech campaigns that shut down court systems in Spokane and California drew national headlines.

When vigilantes led by former law enforcement officer Axel Steele violently broke up an IWW street meeting on Aug. 12, 1913, the Wobblies threatened a free-speech fight they said would bring thousands of members from around the country to protest.

Some historians theorize that Hill, a Swedish immigrant who joined the IWW while a dockworker in California, first came to Utah in answer to that call.

Salt lake City Riot

The Salt Lake Herald-Republican reported on its front page about a riot at the corner of 100 South and Regent Street on Aug. 12, 1913. Axel Steele, seen pictured on the page, led a group of men in an attack on an Industrial Workers of the World rally. Steele was shot, but not seriously injured, by IWW member Tom Murphy and was heralded as a hero for his role in the incident. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

↕ More

IWW backlash

"I.W.W.'S MUST LEAVE UTAH, SAYS SPRY" was the headline over a Salt Lake Telegram story describing the execution of Joseph Hillstrom, known as Joe Hill, on Nov. 19, 1915. The execution took place just before 7:30 am. and the Telegram was published in the afternoon. Jeremy Harmon, The Salt Lake Tribune

tsemerad@sltrib.com @Tony Semerad

Join the discussion

Join the discussion